Tick Talk: Lyme and Other Tickborne Illnesses with Dr. Jeff Holmes

July 18, 2023

In this talk we dive into all things tickborne – Lyme, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Rocky Mountain Spotted fever, and the like. These little creepy crawlers carry a whole slew of pathogens they can pass to their host. Join Dr. Jason Hine and Dr. Jeff Holmes in this walk through the different vector-borne illnesses, how to diagnose, and treat them.

Tick Talk- Lyme and other tickborne illnesses with Dr. Jeff Holmes – The SimKit Podcast

Transcript

Jason Hine: Hello everybody. I am Jason Hine. I’m sitting here with a good friend of mine. We’re going to be talking a little bit today about, I guess some things that really gross people out.

Jeff Holmes: Uh, freak people out.

Jason Hine: Freak them out! Jeff, what are we gonna be talking about?

Jeff Holmes: I tell you, in Maine we don’t have venomous snakes. We don’t have any venomous spiders. But people are freaked out about ticks.

Jason Hine: Ticks, we’re talking ticks today.

Jeff Holmes: The tiniest little things. You can imagine the size of a poppy seed, but for some reason they will still elicit an emergency department visit for a lot of anxiety.

Jason Hine: They will.

Jeff Holmes: So I think…

Jason Hine: They’re very anxiety provoking.

Jeff Holmes: I think it’d be cool to talk a little bit about kind of what goes into this anxiety, how to address it, and then see if any of that anxiety is actually real. If there’s some stuff behind this that we need to really seriously consider for both the symptomatic patient but also the asymptomatic patient that comes in.

Jason Hine: Yeah, perfect cause those little bad boys, they harbored a lot of a lot of creepy crawlies in their guts, I guess. So we’re gonna dive into that a little bit but, let’s open with a case if we may. I’m going to kind of give you a simple case, tell you the superficial way that I would manage it, but I think there’s going to be more to the conversation. So we’re working here in Portland, ME, where Jeff and I live, reside and work. We have an 8 year-old patient come in that’s brought in by their parents for an embedded tick found during bath time. They removed the tick and brought the child for evaluation. They of course have their medical degree from Google MD and want to know if they should have antibiotics for this tick infection. They are unsure of how long the tick may have been embedded in their child.

Jeff Holmes: Hmm this is tough, I don’t think I’ve ever seen this case before.

Jason Hine: Never heard of that? Never heard of that.

Jeff Holmes: Oh it if you live in a Lyme endemic, you’ve probably seen a few patients that come in mostly concerned about Lyme, but I think it would be really helpful to talk about, you know, what’s the risk of other tick-borne illnesses because there’s certainly a lot of other things that that ticks can give you. So this is this is a great a great clinical conundrum in some ways, because we want to be good antibiotics stewards but we want to know if there’s a real benefit to giving chemoprophylaxis and if there is kind of what’s the risk benefit ratio, what’s the risk of giving these antibiotics, the cost, potential side effects, how many do you have to treat? So a lot of really great questions, and I think it it comes down to you know, tick-borne illnesses. They give you a lot of things they can give you a lot of things. They give you Lyme, they can give you Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Babesiosis. We can go on and on, but there’s a lot of stuff and I think it’d be helpful to go through a couple of scenarios here. We’ll talk about one where a patient maybe has a little bit more symptoms, but then also I think the crux of it is going to be this, this patient that’s asymptomatic. When do we treat and if we treat, how long do we treat because, I think the big thing we’re worried about is, is Lyme disease and unrecognized Lyme disease progressing into some of the chronic problems of and that’s been documented and certainly can be problematic. Although rare, it’s still a serious, um finite possibility. So, we’ll talk a little bit about that.

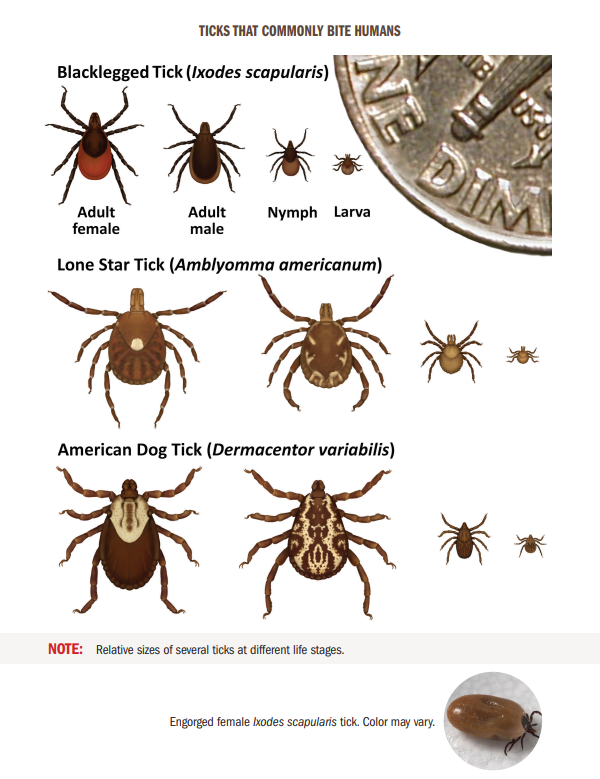

Jason Hine: Can I give you my superficial answer to that question? My understanding and then ask you about, does this hold weight? Cause I think if you live in an endemic area where there’s Lyme or even some of these other ones that Jeff just mentioned, you probably come across some of the IDSA recommendations, right? We’re going to talk about Lyme prophylaxis here primarily. And we’ll get into more about the lack of evidence for prophylaxis in the others. But there’s kind of a few categories or few checkbox you have to hit and then you say sure, maybe I should give these people a dose of DOXY. So the first question, is it a Lyme disease carrying tick? And the primary tick that does this is going to be the black legged tick, the deer tick and technically called the Ixodes scapularis.

Jeff Holmes: That’s pretty good, yeah. I’ve been, I’ve been practicing on YouTube for how to how to say it.

Jason Hine: Yeah, so if you find that it’s identified as an adult or nymphoidal, which is that stage just become before coming the full born adult tick. If you recognize that it’s a deer tick or an Ixodes scapularis tick, that’s one check. The tick has been estimated to be attached for less than 36 hours, a day and ½, check. Prophylaxis can be started within 72 hours, from when the ticket was removed. And the local rate of infection of Lyme disease is greater than 20%. That’s gonna be a tough one. You have to know where you live and have a general sense of how prevalent the disease is there. But that’s the number that the IDSA gives, and then of course we’re talking about Doxycycline. So you need to have a circumstance under which DOXY is not contraindicated.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, that was awesome. For the asymptomatic patient, I think that summed it up really nicely and that’s kind of the IDSA’s bullet points and it sounds really straightforward, but when we dive into these a little bit more, there’s certainly some nuances and subtleties you could take several different approaches. You could you could, be the risk-averse provider that wants to give antibiotics to everybody that’s had any sign of a tick on them, you could give antibiotics, prophylactic antibiotics, not the patients symptomatic right now, just prophylactic antibiotics to only those you think are higher risk. And some of those factors we’ll talk about. Or you could decide not to give antibiotics to anybody and just wait and give really good counseling to the patient on how to look for signs of a tick-borne illness and what the IDSA says is within the next 30 days.

Jason Hine: 30 days of observation, okay.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah. The majority of folks you know, will have a fever, a rash and flu like symptoms. Lyme maybe, you know, 20% won’t have that rash. So that’s why I think we’re thinking about it a little bit more plus the fact that it has been shown to be to reduce the incidence of progression to Lyme disease. So we’ll dig into that a little bit more.

Jason Hine: OK. So yeah, I guess as you mentioned that there’s a couple things that make that those recommendations from the IDSA kind of challenging. How often do they say, absolutely, this is a deer tick?

Jeff Holmes: Gosh, yeah. I mean that’s the hard thing. And you know we’re talking about, What’s the textbook answer or when you look up to date, but that’s really hard, sometimes, you know, patients will bring in the tick and that’ll be great. And so if you’re not familiar with, you know the black legged tick or the ixodes tick that carries Lyme. It’s just a google search away to be able to take a look and if you have the tick right there you can easily match it. I think what you mentioned, which is really important, is that the nymphal stage tick, nymphal stage tick that is going to be the one carrying the majority of and transmitting the majority of Lyme disease and those are super small. They’re size of a poppy seed. You know, my, my kids sort of roll their eyes during the summer when we’re up at camp because every night we’re doing tick checks and I know all their freckles and they’re like, dad, just do this again and I am like, yep, every day and the two rules of thumb I go by is the freckle that moves is not a freckle, probably a little insect, and then the freckle with legs is also probably not freckle, so…

Jason Hine: That’s a fair rule.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, so looking at those and, and really it’s those small nymphal stage ticks. And interestingly, you know, the adults still still carry Lyme disease, but they’re they’re easier seen, they’re a little bit larger, um and so we tend to see them flick them off quickly but the…

Jason Hine: Or they get removed early if they’re embedded so that they don’t have that 36 hours to kind of get it out of the gut and into the, our bloodstream, right?

Jeff Holmes: Totally, yeah, yeah.

Jason Hine: And so say we have a pretty reasonable suspicion they either bring the tick in with them. We’re getting kind of that oh we you know they, they know when they bathe the child the night prior, they didn’t see this on the arm or on wherever they found it in the case that we presented and we’re starting to add up, we’re starting to tick some of those boxes from the IDSA, I guess there’s it’s more than just a, yes give the medication or no, don’t give it. There’s a lot of nuances to that in terms of how many people need to be treated, what are the risks for, you know, antibiotic administration in terms of side effects, so what, what are some of those things that we need to consider?

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, so just thinking conceptually, kind of big picture, when I think about does this patient need antibiotics or not? I I think there’s a couple questions that come up and a couple of points. One we know that Lyme disease can progress to chronic problems and you can imagine the IDSA society is really aggressive at trying to prevent disease. I think that that’s reasonable. The other thing that’s, you know, really important is that potentially 20 sometimes cited 30% of patients don’t have that rash later with Lyme disease, so it’s a thought that maybe they could progress to those chronic sequella or secondary infection without seeing it clinically with the rash and, and the more obvious, yeah, so I think that’s, you know why it’s really important to recognize this and then thinking about when are we going to chemoprophylax. So it’s really a risk benefit. So we want to prevent you know, the secondary illness and we want to know if it works which you think it does and we can talk about that a little bit more in detail and then we want to balance it out with the side effects. And so we’re talking about, you know, one time dose of chemoprophylaxis, some of the studies used some prolonged courses of amoxicillin, but we’re really right now talking about that single dose of Doxycycline and, and for the most part, it looks pretty safe with with probably lower risk side effects. So the biggest study we have is the New England Journal of Medicine, 2001 article by Nadelman that had the most number of patients looking at Chemoprophylaxis.

Jason Hine: And this is looking at DOXY correct because part of the problem was when you look back at the literature, amoxicillin was used a lot, as you mentioned. And the IDSA recommending kind of against that now because it’s just not as effective. So in order to be a good prophylactic, it has to work right. So we’re talking again, we should have stated this plainly, but we’re talking about a 200 milligram dose of DOXYcycline, taken one time for adults.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, yeah. And in children, you can also dose it up to that 200 milligram. So that’s something that you know we’ve talked about in the past or about the risks. Yeah, so let’s get into some of those risks. So we talked about the risks of teeth staining with children because it binds the calcium, and that’s really been shown to be some of the earlier generation antibiotics that are in the family with DOXYcycline. And it’s not really showing as much with DOXYcycline and not with that single dose. And so IDSA has really given us the green light to to be able or the I think it’s American Academy Pediatrics…

Jason Hine: Yeah, AP has gotten behind it as well. So both the IDSA and the AP, which is great, to have the IDSA, but I’ve put a lot more weight on the American Academy of Pediatrics saying, the dose of DOXY at you know up to the 200 milligrams or 4.4 MGS per kg is going to be okay and it’s great to have the IDSA say that’s safe, but I agree it really puts a lot more weight to have the American Academy of Pediatrics behind that recommendation that that dosing is okay even in children less than 8.

Jeff Holmes: Yes, yeah, which is great. It’s probably really the best. It’s been the one antibiotic that’s shown to work for chemoprophylaxis. Obviously in the IDSA’s guidelines and recommendations not to use an alternative that there’s an allergy or contraindication to DOXY.

Jason Hine: Interesting, right, so if we on that last point from the IDSA check box that we we’ll put in the show notes as well. DOXYcycline is not contraindicated, so if we are finding there as a true contraindication, which is again not age, not for children, but say an allergy and anaphylaxis, they’re actually recommending against prophylaxis in those people because we don’t have another agent that has a similar efficacy.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, that that has been shown. The literature is really interesting when you get into it and you know before this larger study really showing convincing efficacy, all the other studies were much smaller numbers of patients and the incidents even in endemic areas of Lyme was, was really low, usually around 1 to 3% of getting Lyme.

Jason Hine: Of people getting Lyme disease.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, an endemic area so it was hard to really show a benefit. So yeah, it’s really just the DOXY that’s been shown. So if there’s a true contraindication, you know the incident still in endemic here is so low that I think the IDSA says, you know, just educate, look for clinical symptoms, and avoid any other antibiotic for prophylaxis.

Jason Hine: Interesting. So yeah, that that 1 to 3 percent. So if Lyme disease is even in heavily endemic areas, it’s still that low and people are getting bit by ticks that is going to affect your NNT, your number needed to treat. And we really got to weigh your risks that we’re starting to talk about pretty heavily. So teeth staining, certainly in children, what other kind of risks or side effects do we need to consider in these patients?

Jeff Holmes: So we think about, you know whole spectrum of things and antibiotics we think of allergies minor like rashes and more serious life threatening allergies like angioedema and anaphylaxis. Certainly with DOXY, we think about some of the DOXY known things, so pill esophagitis. It can tend to be pretty upsetting to the GI tract and nausea and vomiting are actually pretty common in the treatment group and that Nadelman article. You know, it was really nice to see though in in both the med analysis that was done. As well as the that was done by Warshawski. And then also the Nadelman study, is that the majority of reactions were pretty benign, it was nausea, vomiting maybe a little bit of diarrhea, maybe a little bit of rash, but no serious life threatening legit reactions to that one time dose of DOXY so that was that was pretty…

Jason Hine: And that makes sense because we generally think of DOXY as well tolerated.

Jeff Holmes: Nice to see.

Jason Hine: But we do have to think about that as what like 30 some odd percent of people are going to have some kind of GI upset or other minor effect or side effect of DOXY. So that needs to be weighed against that maybe 1, 2, 3 percent risk of going on to have Lyme disease.

Jeff Holmes: So you know all those things are pretty rare, but maybe collectively the risks of DOXY and also the cost has to be weighed into the benefit and in first like we said just we need to know works, which we feel like we do and then we need to know kind of what’s maybe that tipping point that that point of equal points, where the benefits of treating are going to outweigh the risks and downsides of antibiotics and all the things that we talked. Yeah and so that’s certainly, you know dependent on your disease prevalence so being in those Lyme endemic areas, those are really the ones that we’re going to be thinking about with those high percentage of Lyme that IDSA will recommend.

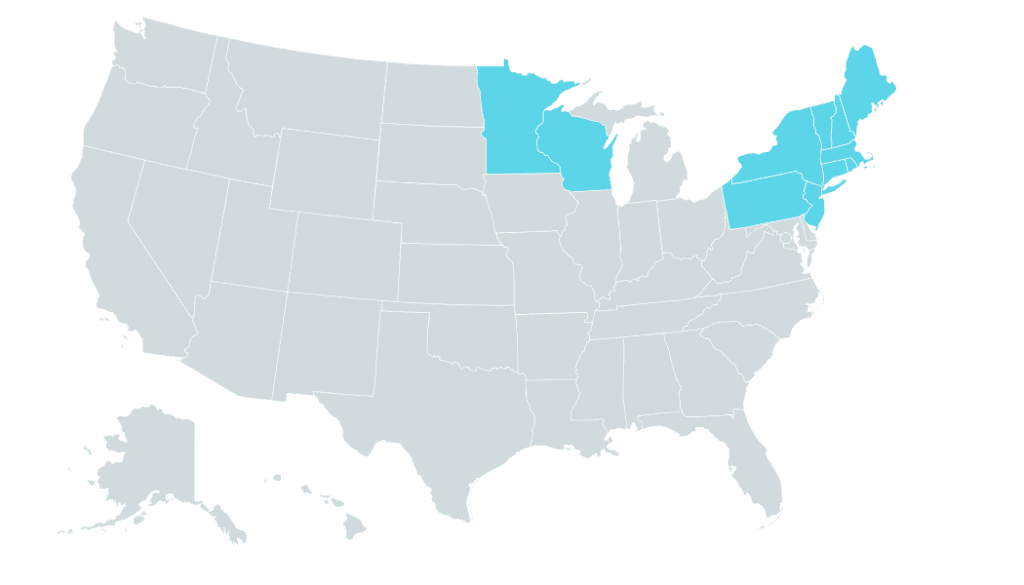

Jason Hine: Yeah. And they’re specifically saying 20% and I have to say. I don’t know. I haven’t sampled all the ticks in my area and tested them for Lyme, so I don’t know specifically. I think of us as an endemic area. I have no literature to say we’re at 20%. God forbid we’re at 18%, you know. Then maybe we’re overly prophylaxing people, but that’s the number to keep in mind and kind of what areas would you say are regions that have that endemic prevalence?

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, that’s it was a tough question to try and figure out, you know, looking at some of the sources, it sounds like you know, a lot of the New England areas, Mid-Atlantic states, the jersey, those are some of the areas where you’re going to see those in some of the Midwest as well, Pennsylvania and New York. My home county of Westchester. Gosh, we talked about this. There 800,000 residents and I saw in one year 180 tick. 180,000 tick bites. So certainly there were multiple offenders, but it gives you an idea about the…

Jason Hine: That’s a lot of bites. And then Wisconsin, Minnesota, they get lumped in there pretty heavily, right?

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, don’t forget those Minnesotans. Hey, you know, and and Wisconsin. Awesome two places, but unfortunately, that goes along in medicine. If you’re good people, you’re probably going to get some…

Jason Hine: Nasty diseases.

Jeff Holmes: And it includes tick-borne illnesses. So, yeah, we’re thinking about these areas where we’re thinking about risk benefit. Are we in an endemic area? If we’re not and that’s why the IDSA kind of clear up front, you know, don’t worry about treating unless they’re symptomatic. Otherwise, if they’re asymptomatic, just watch for disease because the prevalence is so low. But in these endemic areas, that’s where I think you’re gonna get the better NNT.

Jason Hine: Perfect. So kind of maybe coming full circle if we can to that to that kid. What’s your impression of that child and whether or not they get Doxycycline?

Jeff Holmes: All right. So thinking about this kid that’s coming in. We want to risk stratify because I think this is a kid, reasonably could be given antibiotic prophylaxis. But I think we’re going to get a little better number needed to treat if we risk stratify and see if this was a high risk exposure for Lyme or if it was lower risk, so you know the first thing we’re going to look, is if it was the tick attached. And pretty simple if you can flick it off, it’s not attached. If you have to pull it off and certainly is a small talk in itself then that’s an embedded tick and so that is, you know it causes us to think more about it and we ask is it a member of you know the Ixodes species, the ones that carry Lyme? That seems like a straightforward question, there’s lots of Google pictures, but interestingly, some of these studies that actually measured how well Physicians could judge this, it was pretty poor. You know, maybe 30, 40% were accurate. Some of the some of the insects that were submitted were spiders were some of these studies. So it was a little comical even, you know, “The experts in the emergency department” that are helped that helped sort this out for patients were not even sure. And then you know, if you have that patient who is freaked out, pulls it out, flushes it down the toilet, who knows. But you can start with kind of if they had a picture if they could overall, give a description of the size. So certainly dog ticks are not thought to carry Lyme, and that’s something you could easily differentiate based on the size.

Jason Hine: Right. Sure, larger tick

Jeff Holmes: So I’m going to ask is, is it was it embedded? Do I think it was the tick that’s going to carry Lyme? And was it nymphal or adult? So we’re going to talk just generally size and I think the good rule of thumb we talked about before is a nymphal stage tick, which is much higher risk, is is more of a poppy seed like size and again these are the ones that will probably not going to see so they have more time to feed and bed and regurgitate that lovely bacteria into you and give you Lyme. And then the other question, which is interesting is, is how long was it attached? So you would think that just having that tick embedded in you is a risk and that’s what freaks people out, because I think that you know, maybe equivalent of a needle stick. There’s an instant risk of transmission, but this has been studied pretty well. And so the risk of transmission is really probably negligible for the most part, 36 hours. So if if they have said less than 36 hours, then you could, you could assume that the risk of transmission is essentially nil, and that’s part of that IDSA guidelines. Interestingly, the you know the bacteria that’s in the gut. It only gets regurgitated if you will into you after that time period.

Jason Hine: Yeah, the spirochete.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, the spirochete. You want to, you want to pronounce it? Borrelia burgdorferi (BB).

Jason Hine: Perfect, nicely done.

Jeff Holmes: It just rolls out the tongue.

Jason Hine: But I just wanted to also say that that data is super interesting how they got to that. They just put a bunch of ticks on rabbits and pulled them off at different time intervals to see when they developed the BB.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah and they would culture the ear.

Jason Hine: Yeah, and so it’s reasonable data. It’s not perfect, but that 36 hour rule seems it held up in those rabbit trials and then they have some patient based data as well. But that’s the time point, 36 hours is really when the transmission from the gut into the human host happens.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, yeah. And gosh, how do you, how do you guesstimate that? So you know, I’m talking to mom and Dad. But I’m, I’m asking, you know, you know where is the tick, so is it in a a relatively reasonable area to see it? So is it, you know, on the leg where you would see the kids, shin in the summer, a lot. Their wearing shorts, or is it up in like a inguinal fold and they may not see it, so asking when the last time was they saw that body part without the tick is an obvious question. When was the last bubble time and I know with my 8 year old, it’s it’s struggled to get her to take a bath every day, so it probably wasn’t yesterday.

Jason Hine: Yeah, sure.

Jeff Holmes: So just kind of a reasonable guesstimate of maybe how long that that tick was embedded, I think is just the most practical way that we’re going to do it. You know, and some of the things I’ll talk about too, did they just come here to vacation, their on a plane yesterday and it took a hike, you know, today.

Jason Hine: Yeah, good point. Good point.

Jeff Holmes: So, you know, what was the activity that we think may have been higher risk and endemic areas just living and just walking around your backyard is certainly a risk for us to get a tick but, yeah, if you could somewhat risk stratify their, their lifestyle to sort of pinpoint when that tick might be on, that’s another helpful way to kind of sort that out. And then the other thing you know, we’re talking about, where is the, what’s the local infection rate? So talked about all these ways to risk stratify the other way is certainly with the local infection rate, so the big areas that we’re talking about, you know our Mid-Atlantic, New England area, Minnesota, Wisconsin in the upper Midwest. So it’s these areas that are going to have the highest incidence of Lyme. And so that’s going to make it something we may want to treat. So yeah, I’m looking at all these questions. I’m asking mom and dad, I’m trying to do some research and if I think there’s a reasonable chance this was probably the Ixodes tick, that was nymphal stage, that was fed for a fair amount of time and I’m in Maine. I think that would be reasonable to give a chemoprophylaxis. And so like we said earlier, we’re going to dose that per weight for the kid up to the 200 milligram dose.

Jason Hine: 4.4 megs per kg up to 200.

Jeff Holmes: Yep, yeah.

Jason Hine: Yeah, cool. And so that’s kind of the approach in a starting superficial, we’re looking at the IDSA recommendation, the patient with the tick bite, zero symptoms. You can look at the IDSA and say all of that makes sense, but when you actually start to try to apply that in a clinical setting with real patients, it gets pretty complicated. The parents think it was a deer tick. Well, what does that mean? Like what? What did it look like? Can you compare it to charts? How long was it taking in, attached? Was it in gorged? What’s your local infection rate? These are questions that we need to kind of think about before we see that in our summer time patients. So that’s a great review of the patient without symptoms.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, actually, you know that I think that’s an awesome summary. The last thing I’d add is that decision making is best evidence plus shared decision making plus decision preferences.

Jason Hine: Sure, sure.

Jeff Holmes: So you know certainly there’s a lot of anxiety that goes around ticks. And I certainly if it’s the right move and the right thing for the patient, we’ll want to talk them off the antibiotic ledge. But if I’m really just not able to get through and they’re very risk averse, I’m not going to sweat giving, you know, a one time dose of Doxycycline for those folks. So I think, yeah, I think it’s a certainly a blending of the best evidence out there and then decision shared decision making with family and the patient.

Jason Hine: Yep, you definitely have to kind of just… the family members, the parents and see if they’re understanding of the ideas of the you know, if this really is a low risk exposure, if it’s clearly a dog tick, but they’re not sure they’re convinced it’s a deer tick and you’d need to talk them off that ledge. It’s it’s a patient specific thing, if your department’s very, very busy, that’s gonna affect your ability to transmit that correctly. If you think they’re gonna go, if you don’t give me this information, I’m going to go right to the next minute clinic, that’s not going to be patient centered care and you need to take that in mind. But I think when we’re dealing with such shades of gray and we’re talking about risk benefits, then you have to take in that that risk aversion and that anxiety that comes with it as well. If it’s clearly a dog tick, I would never say give the dose of DOXY to appease parents. But if we don’t know if we don’t know how long the tick was involved, that’s going to come into play much more readily.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, that’s that’s a great way to summarize it. If there’s any sort of uncertainty and and although a watchful approach is, is certainly reasonable, if parents want antibiotics, if the patient wants antibiotics. Yeah, I think that would be a a right way to go to.

Jason Hine: Perfect and kind of that, that last element that we didn’t hit that hard because it doesn’t come into play as much as that 72 hour rule, so you want your antibiotic to start within 72 hours, and it sounds like that’s basically based on you need your single dose to be effective. And if there’s replication above which that dose is going to actually remove the infection, that’s not prophylaxis, right? That’s not going to prevent disease progression. That doesn’t come into play as much in my mind in the ED because they see a tick, they remove a tick. They’re there 5 minutes later in the department. They’re not, I saw a tick on my body six days ago, and now I want that evaluated without symptoms. Is that what, what’s your experience with that?

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, exactly. Either they still have the tick in and they just for some reason couldn’t figure out how to get it out? And so they come.

Jason Hine: Yeah, sure.

Jeff Holmes: In and get some reassurance or they just have the tick and they have anxiety about needing antibiotics. So yeah, I think practically we’re going to see these folks within 72 hours, but it’s important to point out that when chemoprophylaxis and Doxycycline was studied, it was within that 72 hour window. So those are the going to be the ones that we’re going to consider it. Beyond that, you know, there really isn’t evidence for it, and it’s recommended to to not give chemoprophylaxis and just sort of watchful waiting.

Jason Hine: Perfect.

Jeff Holmes: All right. That was a great case in discussing Jason, let me let me throw one at you now. So you have a you’re working here in Portland or Bedford where you spend the majority of time, just South of Portland, and you have a 65 year old female who has been out gardening.

Jason Hine: OK.

Jeff Holmes: And so she pulled the tick off herself a few days ago. She didn’t think much of it, she doesn’t freak out. She’s seen ticks before, but now she’s having kind of some mild, achy symptoms, maybe subjective fever, and she’s worried about a tick-borne illness.

Jason Hine: OK.

Jeff Holmes: So how do you evaluate that patient that presents in that short term after a tick bite for a possible tick-borne illness?

Jason Hine: So she’s kind of presenting with the vagues, it sounds like.

Jeff Holmes: She’s got the vagues.

Jason Hine: She’s got the vagues, and if she’s an avid gardener, there’s a decent chance you have to think that that exposure has carried on throughout.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, yeah.

Jason Hine: And we didn’t really get into this a lot, but the month that you’re presenting matters, right? So we have to think about the different stages of all of our different ticks. And as we talked about the nymph tick, nymph stage of the Ixodes scapularis is going to be the highest transmittance for Lyme. And they’re most active, we’re finding kind of that June, July time frame May, June, July that early late spring early summer is really when they’re most avid and most interested in humans, so that’s going to come into play. But this lady, she’s been gardening, I’m assuming throughout the spring and into the summer, and probably getting exposed to several ticks in our area. So I kind of want to talk a little bit about the symptomatic patient and we’re going to talk about a couple, two different geographies and five different diseases.

Jeff Holmes: Awesome. Yeah. Yeah, I’m ready.

Jason Hine: You ready? We’re gonna hit it pretty hard and quick. So New England and that Upper Midwest, Wisconsin and Minnesota, those have 3. One area the I should expand that the Northeast New England gets all the credits. The northeast, right, it even extends New Jersey down in that region, Pennsylvania includes Lyme, and then the the upper mid or the Midwest, Wisconsin and Minnesota. That area anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Lyme disease.

Jeff Holmes: That’s a lot of -osis.

Jason Hine: There’s a lot of osises, so let’s talk, let’s talk quickly about each of those a little bit. So anaplasmosis, again New England, upper Midwest. The presentation for these three diseases, I’ll say them in each category, but they’re going to be essentially the same fevers, chills, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias is often kind of the later progression as we talked about in terms of secondary signs for especially Lyme disease, but fevers, chills, malaise, myalgias, headache and GI symptoms. You’re going to kind of see that in in all of these. Rash is less common in Anaplasmosis than it is in Lyme, certainly. And then so say this lady comes in with that presentation, we probably we’re dealing with a symptomatic patient. If she’s, you know, 65, we’re we’re seeing in Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, they kind of extremes of age as the patients that may get more extreme disease. So 63, 65 maybe not 72, 78, 80 you get in a patient that’s really got the the vagues, but it’s got it bad. Maybe tachycardic, pretty high fever. These are people I’m gonna consider actually pulling laboratory work on. And so the labs for anaplasmosis, this is also going to be a little bit redundant as you’ll see. We’ll see some anemia, some low platelets, the thrombocytopenia, a little bit of a transaminitis, a LFT bump and then there’s that absolute lymphopenia. So those will be labs that we’re seeing.

Jeff Holmes: And those aren’t subtle. I mean, I’ve, I’ve seen it, I’ve seen a few of these. Those kind of it really jumps out to you that just majority of the cell lines being down.

Jason Hine: Yeah, it’s a, it’s a pretty decent pattern recognition and the way that I’m always kind of seeing that is like, oh wow, they have a low white count and they’re platelets are down and you look up and you see their LFTs are slightly bumped and then it clicks kinda in my mind. That’s the way that these cases have worked for me that that pattern recognition. Why do they have a little transaminitis or you see the transaminitis and then you see the thrombocytopenia like oh, this is, this might be that. So in terms of diagnosing these diseases, there’s a little bit I don’t want to get too far into the weeds, but Anaplasmosis you can do blood PCR, whole blood PCR, or this is an intracellular disease as is Babesiosis, so you’re going to actually see in a blood smear you’re going to see the neutrophils are infected with the anaplasma. So you can do a blood smear or you can do PCR treatment, another redundancy DOXY 100 milligrams BID. This is 10 to 14 days. Now prophylaxis, we talked about Lyme prophylaxis already, across the board, we can say there is no prophylaxis for any of the others, so that’s anaplasmosis.

Jeff Holmes: Got it.

Jason Hine: Questions?

Jeff Holmes: No, I think that makes sense. So you know we talked a little bit, so fevers, chills, raggers, kind of flu like symptoms and certainly the flu, isn’t that common in the summer when you know when these tick-borne illnesses are. So that kind of helps us differentiate and you’re going to see those kind of cell lines being down, your anemia thrombocytopenia transaminitis, so hopefully that pattern recognition, because that’s kind of a unique thing hopefully that will really stick out to you in this patient with their clinical suspicion for tick-borne illness. And hopefully that’ll seal the deal. And then we talked about DOXY, 100 milligrams BID for 10 to 14 days and most of these…

Jason Hine: Then their…

Jeff Holmes: Patients for you are going home or?

Jason Hine: Yep, you have generally a home disposition. Anaplasmosis can present rather ill as we talked about in the extremes of age, so rarely not, but usually you’re pulling that blood smear or that PCR or commonly PCR and sending them home on DOXY with the LFT abnormalities, thrombocytopenia with a presumed diagnosis.

Jeff Holmes: Got it. Excellent.

Jason Hine: So Babesiosis. Again, we’re working with that that Northeast Upper Midwest area, again June through August and this is presenting similarly, right? The vague, the don’t feel wells the symptoms of sweats, myalgias, fatigue, headache, anorexia, nausea. Less commonly, you’re going to see the arthralgias, as we mentioned in some of the URI symptoms. And then also Babesiosis in contrast to Lyme disease, is going to have rash as a rare presentation, not as common of a presentation element, but basically…

Jeff Holmes: Okay.

Jason Hine: The physical presentation, the symptoms of Anaplasmosis Babesiosis , really Lyme, are going to be very similar in their nature, barring that, EM rash of Lyme. So headache, myalgias, fevers, chills, and GI symptoms. In terms of the labs here, we’re going to see again that sort of pattern of a little bit of an LFT bump, some low platelets in the thrombocytopenia. But Babesiosis interestingly is intracellular to the RBCs, so it actually causes a hemolytic anemia and with that…

Jeff Holmes: You have your LDH….

Jason Hine: Yeah, if you if you’re smart enough to grab the LDH or if you think to grab the LDH or you’re worried about the disease process, you’ll see an LDH elevation from the homolysis.

Jeff Holmes: Cool, so to compare it to anaplasmosis, just I I try and think simple. There’s a lot of flu-like symptoms. They’re going to have fever, sweats, malaise, rash and both of these is kind of rare. We’re going to treat with DOXY for anaplasmosis, so make it, we’re going to treat with DOXY for Babesiosis .

Jason Hine: Yeah, no, sorry. This is the confusing part and this is where it would be, it’s a little bit challenging in that the Babesiosis is the oddball out. It doesn’t work as well with DOXY, so it’s, Azithro and atovaquone. If people are pretty sick, their can be hospitalized again more in the extremes of age, you’re going to use Clinda and Quinine.

Jeff Holmes: I guess that kind of makes sense, being kind of a, you know, a red blood cell infection kind of like malaria.

Jason Hine: Yeah, you know what, I honestly hadn’t made that connection, but that’s a great way to kind of keep that that line going. I wish DOXY worked for all of these, this is the one outlier. Again, and then no prophylaxis for this disease process.

Jeff Holmes: Got it.

Jason Hine: Alright, so the third in the group of the Northeast and Midwest is Lyme. We’ve talked a fair bit about Lyme already, but the high points is that it’s from the black leg tick or the Ixodes scapularis, most common in the early part of the summer, late part of the spring. The nymphoidal tick is the one that’s going to really hit you hard with it and they got to be attached for 36 hours. Again, the EM rash, that kind of targetoid varying erythema that’s greater than 5 centimeters in diameter. Symptoms, again chills, sweats, malaise, myalgias, they don’t feel great. We didn’t talk a ton about this because it’s a whole other podcast in and of itself, but just to get into kind of the kind of the three other areas that you think in late Lyme. Cardiac, we’re talking about things like conduction delays. Neurologic, the classic and classic doesn’t always mean most popular or most common is the palsy, the Bell’s palsy. Bilateral, Bell’s palsy gotta raise a red flag for Lyme, but you can have different palsies and neuropathies. And there’s actually like mild cognitive impairment that people will get, they get this kind of mental slowing with uh, neurologic, Lyme disease. And then the rheumatologic, which is those arthralgias. But those are kind of, you know, later presentation. Again, labs in terms of this lady, if we’re pulling labs on her because she’s a little sicker, so general labs for Lyme disease not going to have as much of that pattern recognition that you can have in Anaplasmosis or Babesiosis . You know you’re going to get elevated and inflammatory markers. You might have a little bit of that LFT bump as well, but not as much of those sort of classic yel… Thrombocytopenia with the transaminitis and the lymphopenia like you see in the others. So harder to get a smoking gun right off the bat with Lyme disease.

Jeff Holmes: And so what about, you know, are we going to test this woman for Lyme, or are we going to just presume, based on kind of an endemic area, her symptoms and her tick bite exposure and go ahead and treat her?

Jason Hine: Yeah, so that’s a fantastic question. And I think the textbook answer may different, differ from clinical practice a little bit. And so in terms of testing all of these spirochete-based disease processes. Early into the disease course, you know the 7, 5-7 day time frame of symptoms, our tests are not going to be as positive. They’re not going to have the same sensitivity specificity as they do later in the disease process, so. Most of the time they’re recommending in an endemic area with kind of a good constellation of symptoms, a decent pretest probability, either someone that works and is constantly being exposed with ticks, or has a known tick exposure they’re saying treat off symptoms definitely. If you’re not sure, you need to test the testing again. It gets a little complicated and it’s a little bit nerdy, and it may even be a little bit above my level of understanding, to be honest. For Lyme, it’s pretty clear they talk classically about using the ELISA test initially, and these are looking for our antibodies. The human antibodies to the disease process. Talking about IGM, which appears 1st and then IGG, which appears later. So we’re looking for those in, in ELISA, and if that’s positive or abnormal, then we’re going to follow that up with a Western blot test.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, yeah, that’s I think a great way to summarize it too. And we talked about in, in these studies, there’s even endemic areas. There’s a low probability of Lyme, so even though these tests, you know, the ELISA may have a mid 80s sensitivity, that predictive value is probably not going to be very, very good. Especially for the patient who presents early and then also you know, because the pretest probability with her maybe a little bit higher, but in the sort of the asymptomatic patient that people are testing for, it’s more likely you’re going to get a false positive than you are a true positive.

Jason Hine: Right, which gets rather complicated.

Jeff Holmes: So I think that it makes sense for this woman to go ahead and treat her with DOXY based on her symptoms, the endemic area, the tick exposure.

Jason Hine: Totally, I completely agree with that. And you know you’re going to have to, we can go through the if she had abnormal labs in the other areas. You know, if certainly if we’re thinking that it’s pointing more towards anaplasmosis, we’re already covering her well with the Doxycycline covering for Lyme and Co infections do occur. So, if someone has that sort of pattern of lab abnormalities we want to make sure we’re covering for Lyme disease as well. Or if we see those LFT, you know, if we see the findings for the hemolytic anemia that might point us a little bit more towards the Babesiosis you need to consider initiating therapy for that as well.

Jeff Holmes: No, that’s a a really great point because it’s certainly overlap in these clinical presentations, some of these labs. So being able to tease it out certainly makes a difference. You know, when we’re talking specifically about the vicious because that’s got a different treatment and you know, like you said, IDSA says, hey, if if you’re if you’re treating a patient with Lyme, then you’re not really getting better think about coinfections.

Jason Hine: Yeah, sure.

Jeff Holmes: And so that would be a great way to sort of tease that out a little bit more, whether you have a patient that presents to the ED after being on on DOXY for presumed Lyme, something to think about or you know when you’re counseling the patient, giving them DOXY if, if they’re not improving, you know, they certainly need to check in with their physician again.

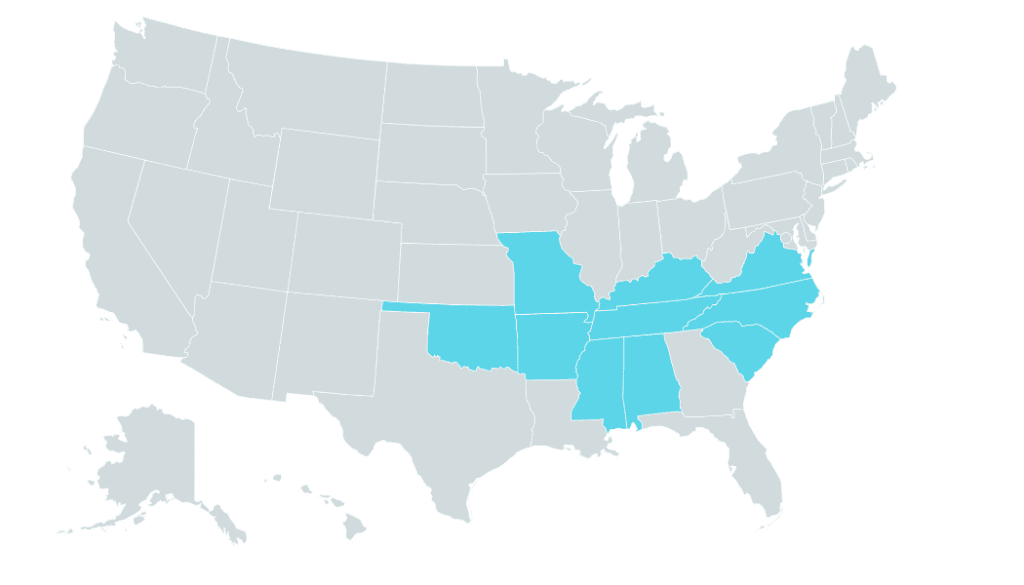

Jason Hine: Yep, to think about specifically Babesiosis, is it’s definitely a lower incidence of disease. If you’re going to shoot for a larger target, you gotta shoot for a Lyme disease, right? In terms of the tick-borne illnesses, but if they have that classic patterning but they’re not improving, you have to think about something that might not be covered by it. So to kind of go over those all together, the difference, there’s a couple different things. There’s that, ELISA and then the Western blot for Lyme and I think I mentioned for Anaplasmosis that we’re going to be doing that, that smear looking for it in the neutrophils are doing PCR for babesia. We’ll also have the option to do the babesial PCR and then a smear looking for intracellular spirochetes. And then so the other demographic area with two disease processes is kind of the southern Southeast part of the United States and the South Central US. And here we’re looking at Ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. So looking at Ehrlichia itself or ehrlichiosis, Southeast ern US, South Central. It’s caused by the black leg tick again, the Ixodes scapularis, but also the Lone Star tick, which is probably a bigger player in terms of transmitting this disease. In terms of thinking about your geography, you know, if you live in this area, if you’re listening to this podcast, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas is about 35% or so of the cases of Ehrlichia. Symptoms a little bit of a, you know, rewind, press play: fever, chills, malaise, they got the myalgias headache, GI symptoms, including, so we talk about nausea, vomiting, some diarrhea and anorexia are common. Rash, for this one, you’re going to see it more in the kids than in the adults, so it’s an element of the disease. The general labs that we’re pulling for Ehrlichia are similar. You’re going to see that they have that leukopenia thrombocytopenia, anemia and the LFT abnormalities. But again, we’re looking at a completely different geographical area. We have a much lower, if no incidence, of those other disease processes.

Jeff Holmes: So we’re really focusing in on this, yeah.

Jason Hine: Well, Lyme, Lyme is a bit of a interesting player. It’s definitely the area that we talked about plus a little bit of the West Coast and there’s a couple of smatterings of it elsewhere and Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis. We’ve really seen it in that demographic, that Northeast and the Midwest.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah

Jason Hine: And so now that we’re talking about the South and Southeast , again, Ehrlichiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever. So if you’re seeing that patient with the tick bite and these symptoms and you’re finding these labs of lead leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and LFT Bump, we got to think about that disease.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, that’s great. You know, one thing I was just thinking about too with any any patient presents with a fever is always trying to take a travel history too. Or not just foreign travel, but, you know, did they just come from there their two week trip in Maine and now they’re not in a Lyme endemic area.

Jeff Holmes: But if I didn’t get that travel history, I might have missed that.

Jason Hine: For sure for sure, especially with the summer, you know, travel for vacation, absolutely. And then for the diagnosis of Ehrlichiosis, we have that PCR again of the whole blood, or you can do the indirect fluorescent antibody or the IFA. This is where it gets a little bit confusing for me to be honest. There’s the ELISA, there’s IFA, similar but slightly different processes. I don’t think that that part is as important. Your lab is hopefully, rightfully testing these patients with either PCR are doing an antibody based test, either ELISA or IFA.

Jeff Holmes: That’s why I just looked at the order sets tick for the Tick panel and I and it clicked.

Jason Hine: And I I think you know there’s value in certainly checking to see what those are because there’s a lot of argument about are the appropriate tests being done especially for Lyme disease or certain, you know, whole blood PCR, there’s argument against doing that. So if your lab is doing the wrong test, that’s probably important to recognize that. Lyme is the ELISA, followed by the Western blot. Here we’re talking about actually doing the whole blood PCR for Ehrlichiosis or doing the IFA. Treatment, simple again DOXY 100 milligrams BID for five to seven days as a minimum, but also they recommend by the IDSA to do at least three days after the fever subsides.

Jeff Holmes: Okay.

Jason Hine: And it’s a 2.2 megs per kg per dose for kids, essentially matching what we talked about already.

Jeff Holmes: Got it, so Southeast ern, South Central US, we’re talking about the black legged tick and the Lone Star tick. Also seeing some Oklahoma, Missouri, some Arkansas kind of similar symptoms flu like symptoms and nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, more often than the kids and we’re going to see some of those similar labs with kind of the cell lines being down… LFT bump.

Jason Hine: And the transaminitis? Yep.

Jeff Holmes: And then good old DOXY. Actually, we’re going to treat with DOXY and treat even for a few days after that fever subsides for three days.

Jason Hine: Exactly, and then our last one is kind of the big bad guy that’s outside of our geographical area. So we should, you know mention that, kind of disclaim, that we’re working in the Northeast but and we’re going to talk about Rocky Mountain spotted fever, but it’s an important disease to know as a tick-borne illness, a podcast talking about these disease processes and not talking about Rocky Mountain spotted fever, would be remiss. So it’s mostly in the Southeast . It is kind of everywhere, but man, 60% are going to be in these five states, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri.

Jeff Holmes: Like all of those states.

Jason Hine: Yeah, like you said, good states, bad diseases. So this is the American dog tick, the brown dog tick or the Rocky Mountain wood tick. Those are the ones that send it so different than some of the other disease processes. We’re we really hate that Ixodes scapularis here because man, it carries a lot of the things we don’t like. This is spread by a couple of different ticks in, in the endemic areas.

Jeff Holmes: So he’s got partners in crime.

Jason Hine: Yeah, so rash is common in this disease, kind of similar to Lyme, but maybe even more so. 90% of patients are going to have this rash. This is can be a pretty nasty looking rash if you look at pictures.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, this is pretty new. This is that pathognomonic, it’s, you know, a big thing that everyone’s worried about. What is what is. What do you, how do you , pattern recognize this rash?

Jason Hine: So I think that kind of erythematous rash with the these pretty chunky macules, macules on top of an erythematous base and then transition in towards having … elements to it, it’s a pretty impressive and and gnarly looking rash in its own right when it presents that way, and it’s pretty pathognomonic in its own in its own clinical context for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Symptoms here a little bit different, pretty elevated fever. The Fever is an impressive part of this, as is the headache. Pretty severe headache, headache, high fevers, Rocky Mountain spotted fever that’s going to be something that you have to think about and then some of those other elements: malaise, myalgias, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and then edema of the eyes and hands. So this is, I have to say, we’re working here in in Maine area. I haven’t seen this disease process, but that’s something that you know, the CDC and the IDSA recognized as an element of the disease.

Jeff Holmes: OK, so I’m thinking this nasty rash and then I’m going to keep my eyes out for that edema with the eyes and hands.

Jason Hine: And this this one can progress. So later symptoms and signs, you know you’re going to get cerebral involvement. Actually, things like cerebral edema and the associated altered mental status. And people can go on to things like ARDS and respiratory compromise from Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Definitely a big player, big kind of a little bit more intimidating disease process to tackle when it when it gets bad like that. The laboratory work, the general labs that you’re going to see here, you know the low platelets and the transaminitis men. Rinse and repeat right. A lot of these disease processes.

Jeff Holmes: I like this. I’m a simple man. I like simple common themes among my stuff, yeah.

Jason Hine: I like the commonalities, recognizing it. Okay, think about tick illness, but then you want to find that little element that might be different. And here in Rocky Mountain spotted fever, hyponatremia and azotemia.

Jeff Holmes: Okay, so Azotemia certainly seems unique in the hyponatremia in contrast, to the other…

Jason Hine: Yeah, to the other tick-borne illnesses, right.

Jeff Holmes: Foreign illnesses.

Jason Hine: So for the diagnosis, we’re going to do our antibody testing again. The IFA, or ELISA, and treatment, what do you guess? What do you think?

Jeff Holmes: Is that the… No, no, no, no. I’m going to DOXY. DOXY!

Jason Hine: 400 yeah. Yep. So DOXY for the win exactly. So Doxycycline, 100 milligrams BID and that same pattern that we saw of five to seven days as a minimum, but you’re going to want to get at least three days past the last fever. All right. So let’s kind of wrapped that up. We talked a lot, we’ve talked a lot about Lyme. We talked a bit about all these other diseases. Let’s sort of take it from the patient side. Let’s talk about the patient without symptoms, tick bite. And the patient with some non-specifics. So, you open up.

Jeff Holmes: I’ll do that patient without symptoms. So they come in within 72 hours. They and they’re worried about a tick, the tick exposure. So we first figure out, you know, there is certainly evidence for reducing the incidence of Lyme and that’s the main thing we’re worried about here is trying to decide if we can give chemoprophylaxis for Lyme, so because we certainly want to prevent some of those long term outcomes. So what we do is I think it’s reasonable to risk stratify patients, not give everybody antibiotics because the incidence is actually pretty low even in endemic areas. So we’re going to ask ourselves some some major determinants of the risk of transmission. So we’re going to be asking yourself, is there actually a tick attached? So, if you can flick it off, then it wasn’t attached. Is it a member of the Ixodes species, the one that carries Lyme? And so, that can be hard to figure out. But we talked about some ways to do that. And we’re also going to ask if it was a nymphal or adult stage? Nymphal is much more likely to not be seen early and much more likely to feed to the point where it can transmit Lyme disease, the bacteria that causes Lyme. And then how long was it attached? So we know that really less than 36 hours, there’s really minimal chance of transmission of Lyme. That can also be a hard thing to parse out, but that’s how we’re going to kind of look at this and then also our local infection rate. So we’re going to add all those things together and our local infection rate, again, we’re talking about really the endemic areas, the areas we mentioned earlier. If all those things are checking out, and I think this patient is probably a reasonable candidate for chemoprophylaxis,

Jason Hine: Yeah

Jeff Holmes: we want to go through those four checklists with IDSA. So we talked about the attached tick being from a deer tick. Attached for greater than 36 hours, we can start antibiotics within 72 hours of the tick removal and that local infection rate was greater than 20%. So maybe a little bit redundant in the checklist, but I first evaluate the candidacy for antibiotics, then look at the IDSA guidelines, and if there’s no contraindication for DOXY, we’re going to be given that 200 milligrams of Doxycycline for an adult. And remember that kid dose…?

Jason Hine: 4.4.

Jeff Holmes: 4.4 mgs per kg up to the 200 milligram, so that’s that one time dose of DOXY.

Jason Hine: Alright, so then the patient with symptoms, and this happens a lot too, patient comes in either, I’m covered in ticks all year, I don’t feel well and these are my vagues of, you know, fever, malaise, myalgias. Or I got a tick bite and now I have those symptoms. Certainly not, I have this classic rash of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, or of Lyme disease. That’s different, right? The patient with symptoms that are very non-specific. We kind of think about that in two different endemic areas in the Northeast and Minnesota, Wisconsin area we’re going to talk about Lyme, Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis. If the patient is relatively sick, we’re going to talk, we’re going to get some laboratory work. So labs for tick identification are considerations. Again, if they are presenting several days, 5, 7, 10 days after the onset of symptoms cause early on, it’s going to be less effective, but we’re going to be talking about the ELISA and the Western blot for Lyme, the blood smear and the PCR for Anaplasmosis or Babesiosis. In the interim, though, if someone is relatively ill with their disease and that’s going to happen in the extremes of age, so our 65 year old, 75 year old, that comes in tachycardic, maybe febrile, you’re probably going to pull your CBC and your CMP and we’re going to see some of those things, the lymphopenia, the anemia, thrombocytopenia and the LFT bump oftentimes for the Anaplasmosis and the Babesiosis . If the anemia is significant and you add on or pull LDH, then you’re going to start thinking a little bit more toward the Babesiosis . If you see that patterning in general of low platelets, low lymphocytes and the transaminitis, you’re going to be thinking certainly about Anaplasmosis and possibly co-infection, or Lyme disease, where you’re going to be using your Doxycycline. And the South and the Southeast, we have a whole other kettle of fish, two different diseases to think about. We have our Ehrlichiosis and our Rocky Mountain spotted fever. So in terms of specific tests there, we’re going to do a PCR of the whole blood or the IFA for Ehrlichiosis and the IFA or the ELISA for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Again, if they’re presenting ill, we’re going to pull those same ups, the CBC and the CNP. If you see the leukopenia thrombocytopenia, anemia and the LFT bump in this area in the South and Southeast , we’re going to think about Ehrlichiosis or Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Add on some hyponatremia and azotemia, then you’re going to be pushed pretty strongly toward Rocky Mountain spotted fever as you’re diagnosed. So if those labs point you in that direction, that’s a sign for active infection. We’re not talking again about prophylaxis here. We’re going to be talking about treatment. Overarching, you’re pretty much going to say Doxycycline 100 milligrams BID unless we’re thinking specifically about Babesiosis , in which case we’re going to use azithromycin or if the person needs to be admitted or is quite ill, then we’re going to be talking about Clinda and Quinine. Sound good?

Jeff Holmes: Sounds awesome, except for the part of getting the tick illness.

Jason Hine: Yes, having the tick bite, getting the tick illness, that doesn’t sound good. As a provider it sounds straight forward enough, I guess. I think it’s…

Jeff Holmes: This is it’s not as murky as it thinks. I mean, I think it’s it’s really based on kind of sound concepts, evidence. I think there’s some generalizations we can make among these tick-borne illnesses and when all else fails, just go for the DOXY.

Jason Hine: Yeah, there you go. So, perfect, so I think as we come to a close, we’d be remiss if we have a microphone and an opportunity for a public service announcement not to talk about proper tick removal. Two things come up: How do you take off a tick? And if you pull off a tick, and there’s a little bit in there, what do you do?

Jeff Holmes: I’ll tell you Jason one of my favorite jobs was right after college, so I got my EMT during college and then I didn’t want to go to Med school yet. So actually I served as a medical director of a summer camp for kids.

Jason Hine: Oh wow

Jeff Holmes: Just outside of Lyme, CT.

Jason Hine: So you might be the world expert in tick removal.

Jeff Holmes: I tell you, I took off more ticks from more kids, and I learned how not to leave the parts embedded and how to get it out.

Jason Hine: There you go. So you use a match, right?

Jeff Holmes: That well, you say, think about, what you’re trying to prevent. You’re trying to get the tick, the entire tick out, but you’re also trying to not have it barf inside. You don’t want to get…

Jason Hine: Inside your skin? Yeah.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, you don’t want to get the bacteria that causes Lyme or other tick-borne illnesses. So yeah, there’s a lot of myths out there about how to remove a tick, so imagine having a nice meal and someone your mouth is full of, maybe we’re up in Maine, a nice lobster meal. Someone brings a torch up under your butt. What are you going to do?

Jason Hine: I’m going to spit my food right out all over the place.

Jeff Holmes: You’re probably going to spit your food right…

Jason Hine: The place, yeah.

Jeff Holmes: Out and I don’t know, that’s the analogy I I think of and I I teach about with removing a tick. How about if I smothered you in Vaseline to suffocate you while you’re eating your…

Jason Hine: Yeah, similar process, probably thrashing maybe.

Jeff Holmes: Similar process, so yeah, I mean we’re providers, we’ve we have a general sense for how to do this, but if, if you know you’re you, don’t remove them as often we’re not going to light a match. Certainly no one’s going to light a match in in the emergency department. We’re not going to smother them, asphyxiate them. They have a really interesting sort of contraption they feed with and then some are barred. And they also secrete this cement-like substance that helps them stay in there. One of the things that I really learned is is grabbing some really fine-pointed tweezers. You can also use some special tick-removing little devices that have kind of a tiny little slot that you can slide into the…

Jason Hine: Yeah, the cards.

Jeff Holmes: Yeah, my wife seems to have, it’s sort of like her immediate emergency rescue tool. She has it on her key chain. She has it in her glove compartment and although, admittedly, she does kind of work in the yard a lot up at up at camp and she does get a fair amount of ticks. So we’re not going to do any of those things that we talked about. We’re going to grab right at the base where it actually inserts and the key thing that I learned was you’re going to do some gentle tugging and the ticks going to decide that it’s not wanted and it’s not welcome. And then it’s going to slowly pop out. So it’s not a grab and yank because when we do that we tend to leave tick parts in which is okay we know that those will eventually make their way out. There’s no indication to remove those. You just sort of sanitize the area over it. But there’s no increased risk of Lyme by leaving those in.

Jason Hine: And by trying to remove that, that’s where you set someone up for a secondary Cellulitis or other you know, they get a nasty inflammatory reaction just cause there’s a little bit of a foreign body that’s irritated and then they think they have Lyme. Just leave it alone.

Jeff Holmes: Totally, yeah, I gosh, I remember a decade ago when I started to see a lot of them here and I would try and anesthetize it and dig them out. And, you know, some of these have little barbs on them. It it’s just not necessary. It can be a pain in the butt to try and to try and do that. So go ahead and leave it in if the patient comes in with the tick bite remaining and that’s the concern. Just some good education, cleanse that area, things will be okay.

Jason Hine: Sure, and so the tweezer you’re grabbing and gentle slow pressure and it’s the tick that’s deciding to let go, you’re not ripping the tick out of the skin.

Jeff Holmes: And again really important to get right at the skin. So not in the body and that’s the thing, you know what, just when I first learned and I was just grabbing and pulling out, I was, I was leaving some mouth parts in there. So what I’ve noticed is just grabbing right at the skin and then you’ll kind of pull in just a little tinting of the skin right at that area and you know, after it may take 10, 15 seconds, just some general tugging and I find that much more effective to remove the tick entirely.

Jason Hine: Perfect. Alright guys, I think that’s everything I could possibly say about ticks. What about you?

Jeff Holmes: The one thing, I like to tell my one last thing I’d leave with is spiders are great. They help catch bugs that bother me. I think their beautiful species, I teach my kids to respect them and…

Jason Hine: I agree

Jeff Holmes: And when it comes to ticks: kill them, burn them, squash them. They carry disease.

Jason Hine: Yeah, get rid of them, yes.

Jeff Holmes: Put them down. That’s my last parting message.

Jason Hine: Perfect. Thanks for listening guys.

Addressing Tick Anxiety

Smaller than a Poppy Seed, but More Anxiety Inducing than a Snake

To fully understand the severity of ticks, it may be easier to describe an Emergency Department Case. The case is about an 8 year old patient, here in Portland, Maine. The parents found an embedded tick during bath time. The parents attempted to remove the tick, and want to know if antibiotics are the next appropriate step. The timeline of the tick is unknown…

To break this case down, it is important to mention the risk of other tick-borne illnesses. Just to name a few: Lyme Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Babesiosis, etc.

Depending on the illness, you may determine the possible medications. When comparing antibiotics, ask yourself:

What is the risk-benefit ratio?

What is the risk of giving these antibiotics?

What is the cost?

Are there any potential side-effects?

How many do you have to treat?

A challenge when treating patients is coming up with a treatment plan when they are asymptomatic versus symptomatic. An asymptomatic patient poses lots of questions, including:

When do we treat?

If we decide to treat, how long do we treat?

Lyme Prophylaxis

If Lyme disease goes untreated, more serious sequalae can, of course, develop.

Ideal Checklist before Prescribing Medication

- Is the patient living in a Lyme endemic area? (Is the local rate of infection of Lyme disease greater than 20%?)

- Is it a Lyme disease-carrying tick?

a. Black-legged tick aka deer tick (Ixodes scapularis)

- Is the tick in its adult or nymph stage?

- Has the tick been estimated to be attached for more than 36 hours, a day and a half?

- Has it been less than 72 hours since the tick was removed?

- In this circumstance, is Doxycycline not contraindicated?

The IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America, lays out straightforward bullet points to follow if you’re a provider, deciding a proper form of treatment. It is also important to consider the type of provider you are. Are you more risk-averse? Or are you more risk-tolerant?

A risk-averse provider is more likely to give prophylactic antibiotics to anyone that has had any sign of a tick on them or those that are higher risk. A risk-tolerant provider is more likely to teach their patient how to look for signs of a tick-borne illness and follow the IDSA’s recommendations for observation for the proceeding 30 days.

Now, you may be asking… What signs should I look for?

The majority of people will have a fever, rash, and flu-like symptoms. It is possible for 20% or so of people with Lyme to not have a rash.

How do I know if the tick is actually a deer tick?

If the patient brings in the deer tick, then it is an easy google search to confirm. However, without the tick present, it can be a challenge. It is also helpful to know the age of the deer tick. A nymphal stage tick, compared to an adult deer tick, is the size of a poppyseed, and carries/transmits the majority of Lyme disease.

Click the image for a full size version in a new tab.

What are the risks for antibiotic administration, in terms of side effects?

With the dangerous possibility of Lyme disease leading to chronic problems, the IDSA is very aggressive at trying to prevent disease. Especially because of the fact that 20 to 30% of patients may not suffer from a rash of any kind. Deciding when you are going to chemoprophylaxis, to prevent a secondary illness, is the next step.

Studies differ with their recommended antibiotic administration. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine from 2001, by Nadelman, had the most number of patients looking at chemoprophylaxis, specifically, using DOXY, or doxycycline. DOXY is reported to have lower risk side effects and be more effective than the prolonged courses of amoxicillin, which was previously recommended. A usual dose of DOXY is 200 milligrams, taken one time for adults and 4.4 mg/kg for children.

A common side effect with previously used antibiotics, in the same family as Doxycycline, was teeth staining with children as it binds the calcium. However, the single dose of DOXY has not been shown to cause this side effects. Additionally, the American Academy of Pediatrics has stated that DOXY is okay even for children less than 8 years-old. If a patient has an allergy to DOXY, the IDSA recommends against prophylaxis because there is not another agent with similar efficacy.

Side Effects

There is a wide spectrum of possible side effects from taking antibiotics including minor allergic reaction, a rash, or even more serious life-threatening allergies like angioedema and anaphylaxis. With prescribing DOXY specifically, effects such as pill esophagitis, nausea, vomiting, a possible rash and diarrhea may occur. It is predicted that 30 or so percent of people will suffer from some sort of GI upset or minor effect after being prescribed DOXY.

What are regions of the United States with Endemic Prevalence?

Based on sources, New England, the Mid-Atlantic states, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, the Midwest region, Wisconsin, Minnesota all have high rates of ticks carrying Lyme. If the patient is not in these regions, and they are not symptomatic, then they lean towards not prophylaxing, and just monitoring the patient’s conditions. However, in the endemic areas, a higher incidence of Lyme is seen, affecting the NNT, the number needed to treat, to prevent one Lyme infection

Circling back to the case: 8 year-old patient from Maine

To recap, the case is about an 8 year-old patient, in Portland, Maine. The parents found an embedded tick during bath time. The parents attempted to remove the tick, and want to know if antibiotics are the next appropriate step. To start the treatment process, Jeff recommends risk stratifying to see if this was a high risk or low risk exposure to Lyme disease. Here is his thought process:

- Was the tick attached?

a. If you can flick it off, it is not attached

b. If you have to pull it off, it is an embedded tick

- If the tick was attached, was it a member of the Ixodes species, the ones that carry Lyme?

a. Identifying the type of tick is actually much harder than expected

b. Studies showed that physicians were correct in identifying ticks 30% to 40% of the time

c. If comparing different ticks, dog ticks do not carry Lyme and are usually larger in size than a deer tick

- Was the tick in its nymphal or adult stage?

- How long was it attached?

a. If the tick was attached for less than 36 hours, the patient’s risk of transmission is essentially nil, according to IDSA guidelines

b. It is vital to gain some context on the patient’s visit… in this case, was the 8 year old on vacation and went on a hike yesterday, or were they on a plane yesterday? These affect the likely length of attachment and feeding.

- What is the local infection rate?

These questions are vital in gaining a full context of the patient’s situation. Jeff, as the physician in this case, would do some research to try to figure out the probability that the tick was from the Ixodes species. He assumes that it was in its nymphal stage, so it fed for a fair amount of time on the patient. Finally, the patient is in Maine, an endemic area. Although the patient is asymptomatic, in this case, it would be reasonable to give a chemoprophylaxis. He would dose that per weight for the kid (4.4 mg/kg) up to the 200 milligram dose of DOXY.

Decision Making = Best Evidence + Shared Decision Making + Decision Preferences

Depending if the patient and their family are more risk-averse or more risk-tolerant will help the physician create a finalized treatment plan. The physician should blend the evidence from the situation and the shared decision making with the family and patient, to figure out the best means of treatment.

Additionally, the physician must take the 72-hour rule into consideration. For the single dose of DOXY to be effective, it must be administered within 72 hours of when the tick embedded itself.

Case 2: 65 Year-old Female Gardener

A Symptomatic Patient in a Higher Risk Position

This case’s patient is a 65 year-old woman who gardens her yard. She has come in due to some mild, achy symptoms after pulling a tick off of herself a few days before. She is worried about having a tick-borne illness. At this point, it is also important to consider what time of year this is occurring. From the months of May to July, the nymph stage of the Ixodes scapularis tick has the highest transmittance rate and is very active. This patient has been gardening from the spring to the summer, and has most likely been exposed to several ticks in the area. There are 2 different geographies and 5 different diseases, which are vital to discuss in this case.

Geographic Region #1 – The Upper Midwest: Wisconsin and Minnesota and the Northeast Extending Down to New Jersey and Philadelphia

In these regions, there are 3 tick-borne diseases to discuss, including Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, and Lyme Disease.

Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis become more dangerous as the patient’s age increases. As the patient’s age reaches the low to high 70s, it may be safer for the physician to get lab work done as well. The patient may be tachycardic with a high fever, so lab work is necessary.

- Anaplasmosis

a. Symptoms include fevers, chills, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, and GI symptoms.

b. Lab work may show signs of anemia, low platelets, thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and lymphopenia.

c. In terms of diagnosing this disease, the physician can do a whole blood PCR, or a blood smear to look at the neutrophils.

d. If labs have a suggestive pattern, the clinician may decide to prescribe DOXY, 100 milligrams b.i.d for 10 to 14 days.

e. There is no prophylaxis for this disease process.

- Babesiosis

a. Symptoms are similar to Anaplasmosis, including sweats, myalgias, fatigue, headache, anorexia, nausea, sometimes a rash, fevers, chills, and GI symptoms.

b. Lab work may show signs of an LFT bump, low platelets, thrombocytopenia, and is intracellular to the RBCs, so it actually causes hemolytic anemia.

c. In terms of diagnosing this disease, the physician can do a blood PCR, or a blood smear to look for intracellular spirochetes.

d. DOXY is not recommended for Babesiosis, instead Azithro and Atovaquone are recommended.

e. In extreme cases, where the patient is very sick and older in age, they may be hospitalized and be prescribed Clinda or Quinine.

f. There is no prophylaxis for this disease process.

- Lyme Disease

a. Comes from the black legged tick, also known as the Ixodes scapularis.

b. Most commonly transmitted in late spring and early summer.

c. Symptoms include chills, sweats, malaise, myalgias, and an EM, Erythema migrans, rash that is greater than 5 centimeters.

d. There are also 3 other areas to mention in the late Lyme disease phase: Cardiac, Neurologic, and Rheumatologic diseases.

e. Lab work may show signs of elevated and inflammatory markers and an LFT bump.

f. Has the highest rate of incidence compared to other tick-borne diseases.

g. Physicians use the ELISA test initially, which is looking for human antibodies to the disease process.

h. If the results come back as positive or abnormal, then the physician recommends to follow that up with a Western Blot Test.

Now, back to the 65 year old female patient…

What is the next step? Should you consider the context in which the patient is in an endemic area, has symptoms, and was bitten by a tick, and decide to treat her?

Well, the answer differs from each clinical practice. In terms of testing all of these spirochete-based disease processes, early into the disease course, the 5-7 day time frame of symptoms, our tests may not be as positive. It is recommended if the patient has a pretty wide range of symptoms, and may work near ticks or is constantly being exposed to ticks, it is best to treat off symptoms definitely.

For the patient, the physician takes into account her being in an endemic area, with symptoms and a tick bite, and decides to treat her with DOXY.

Geography Region #2 – The Southeast and South Central Region of the United States

In these regions, there are 2 tick-borne diseases to discuss, including, Ehrlichiosis and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

- Ehrlichiosis

a. Also known as Ehrlichia

b. Caused by black leg tick, Ixodes scapularis, but also the Lone Star tick, which is probably the bigger player in terms of transmitting this disease.

c. Oklahoma, Missouri, and Arkansas represent about 35% of the cases of Ehrlichia.

d. Symptoms include: fever, chills, malaise, myalgias, headache, GI symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and anorexia are common. Kids may suffer from a rash more than adults.

e. The general labs may show the patient is suffering from leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia and LFT abnormalities.

f. It is important to remember that we’re looking at a completely different geographical area, so the other disease processes have little to no incidence.

g. In terms of diagnosing this disease, the physician may complete a whole blood PCR, or may do an indirect fluorescent antibody test (IFA).

h. The treatment recommended is a prescription of DOXY, 100 milligrams b.i.d for 5 to 7 days as a minimum. Additionally, the IDSA recommends the patient continue the medicine for another three days after the fever subsides.

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

a. 60% of cases are going to be in these five states: North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri.

b. The disease is transmitted by the American dog tick, the brown dog tick or the Rocky Mountain wood tick.

c. Symptoms include a rash (90% of patients suffer from the rash), an elevated fever, headache, malaise, myalgias, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and edema of the eyes and hands.

d. Later symptoms may arise, as well, including cerebral edema and the associated altered mental status. Patients may suffer from ARDS and respiratory compromise.