Crics, Critical Access, & Critical Care

December 13, 2022

We sat down with the great Scott Weingart of the EMCrit blog and podcast (@EMCrit) to talk about the toughest case I ever managed. The conversation covers procedural competency, stress mitigation, skillset decay, critical access, critical care, and a whole lot more. Open the accordion for a full transcript of the conversation.

Crics, Critical Access, and Critical Care with Scott Weingart – The SimKit Podcast

Transcript

J: Hello and welcome, everybody! Thank you for joining us today for our discussion on crics, critical access, critical care, and we have a very special guest in Dr. Scott Weingart. Scott is devil’s advocate on EM:RAP, and is best known for his amazing EMCrit podcast, Fellowship Training Shock Trauma, internationally renowned speaker and an amazing educator. Scott, welcome to the SimKit podcast.

S: What a pleasure to be talking to you, my friend.

J: So I invited you to talk about what is probably the hardest case of my life, maybe not for you, but it definitely was the most challenging case that I experienced and within this case, there’s so much to unpackage, but I see the following topics: stress mitigation in the heat of the moment; the kind of KISS (keep it simple stupid) phenomenon when performing a cric or really any critical procedure; and aftercare of these critically ill patients. Ready to hear the case?

S: Yeah, can’t wait.

J: I was two years out from residency training, still had some green behind the ears, working in a remote access hospital in the boonies of my home state. One of these eight-bed ED’s, 24-hour shifts, you and maybe the hospitalist if they are in house at all, that kind of a situation. Painting a picture for you where I’m at?

S: Yeah, I’m feeling it. You’re on your own.

J: Third shift there, unfortunately, as well, so I had only done two prior [shifts], got a little sense of the nurses and staff but still not a great relationship in terms of that longevity and trust, which is important, too. Toward the end of the daytime, we had a busy shift, settling in for hopefully a long winter’s nap when we got a radio call from EMS for a patient that was a burn victim and to expect a difficult airway. They’re 10 minutes out. So, I go to what could barely be called a resuscitation bay, but our larger bedspace where we do our critical care. I get tubes 6-0 through 8-0, LMA’s 3-4-5, 11-blade scalpel, a [gum elastic] bougie, asked for 10 cc’s of lido with epi and nursing staff knows they don’t have that, so in the heat of the moment as a Macgyver technique, I take some code cart epi, drop a half cc of lido into it, and get ready for the patient.

So, Scott, how did I do with that material list? Anything you would want that I didn’t think of, or what there was extraneous?

S: Look, whatever gets the job done is a good job, so these comments are just icing on the cake, but you mentioned let’s have some lido with epi ready and we didn’t have it, so let’s get people to jury rig it and your brain is occupied with that, too, and that’s the kind of stuff that sends you into maybe an upregulation of stress loop and you have to ask yourself, what is going to be the real necessity of this local anesthetic? You think if I have to do the cric now, I’ll be able do it with anesthesia, then you already now have inserted a barrier to that surgical airway, you know, that if the anesthesia is not enough or if it’s not getting to the right place, or the needle fell on the floor, I think it’s hurting you rather than helping you at that stage when you have to jury rig stuff.

We should be doing it the same way every time, which means it’s a crash cric. Now, if you told me what if I was going to do an awake cric on this patient? Get it at that point, it’s not a rush at that point. But that’s the kind of thing, and I don’t point this out because you did anything incorrect, I point it out because often times things of this ilk happen where people want to prepare for absolutely every eventuality, and it actually steals from the core preparation that really matters, and you did the core prep that matters: range of airway, full bevy of intubation equipment, now if you had to prepare meds, the meds I’d want you preparing is a dual setup of the meds I need for an RSI and the meds I need for an awakened patient, I think that would be a better use of the cognitive space.

J: I think that totally makes sense. It probably took two minutes to do and added to that sense of unfamiliarity that was already very palpable for me, being in that space working with things I’m not as familiar with and it was probably just like you said, cognitive load stress inoculant that I didn’t really need and if I’m tubing a guy that’s burned to that degree of severity, is local anesthetic really going to be helpful? Is that extra epi really going to save the procedure? No. I could easily have spent that time reviewing again the RSI meds or prepping the team one more time? Point taken. Talking about that room a little bit, I’m a newish grad and I’m new to that team. How do you prepare your team for a situation that severe in a place where they don’t really see patients like that?

S: The fact that you’re thinking along those lines already shows an understanding of how the cognitive processes of these critical resuscitations play out. The main thing I get across to my team: This is going to be a crap show, going to be tough, my brain will be at 110% bandwidth. I want anyone in the room who feels I’m missing something or has a suggestion to get my attention, I want them to feel fully actualized to correct anything you see that I might be missing. I need the full team’s help here. We must combine our bandwidth into group think to make this happen because it’s going to be really hard. There’s an excellent chance there’s going to be a really difficult situation, could go to airway disaster, could go to a cricothyrotomy, and now you’ve done a few things: you’ve prepped everyone in the room that they should feel capable of putting in their input, broken down barriers of hierarchy, and they don’t know you as well, so team camaraderie built over years is not there. This is the way to establish it in the moment of the situation. If you’ve already prepped the room for the worst-case scenario of how badly it could go, then when you do the cric there won’t be the same degree of performance anxiety, of “Oh my god, everyone in the room is going to think I’m an asshole because I wasn’t able to intubate this patient and are going to think I’m a failure.” Instead, they’re going to be like, “This doc was so smart. He predicted before the patient arrived it could get to this, and he was having us all prepped to be able to help. That’s an amazing amount of foresight, this is a great doctor.” Forget about what’s going on in their head. It’s what goes on in your head and by prepping the team for worst case scenario, you’re prepping your own head for worst case scenario.

J: That makes total sense and I think in bringing those materials out, I spoke with them specifically, “I don’t know what this guy’s airway is going to be. These materials are for cricothyrotomy.” I think one of the things I wasn’t sure about doing, and I’m curious to hear your input on, is specific roles within the nurses and ERT’s. Do you designate in that regard when there’s not clarity what’s going to be needed or do you leave it open ended?

S: In all my resuscitations at this stage in the game, it’s been like this for eight years, I want to have a doc code leader and nurse code leader for any resuscitation. You establish those roles up front. I am the doc code leader, or it could be the fourth-year resident and you as the attending are just backup, it’s fine as long as everyone in the room knows who the doc code leader is. Then the nurse code leader becomes the person you can ask for any role to be assigned, nurse code leader assigns auxiliary roles: nursing, clinical assistants, blood bank runners—they do all those in addition to nursing roles. As the doc code leader, I only have to look at one person and know their name, and I can say, “Jim or Connie, I need blood,” and it’s for the nurse code leader to figure out how to make that happen. That allows for in-the-moment role assignments. There are some things depending on the case that you should assign ahead of time: Who’s going to take the first pass of the intubation? Could be you or the third-year resident, who gets one pass, you do the next two. If that fails, surgical airway. Respiratory therapy, you gotta make decision up front what you want them to be doing, otherwise it becomes a real cluster because they think it’s my job to bag, but you want to bag because you want to feel the compliance of the patient. Establish that ahead of time. If you want to make the respiration therapist role to be once we need the ventilator, make that happen and help me out by plugging things into the oxygen on the wall, that’s fine as long as you establish it ahead of time. If you leave it ambiguous, people are going to be running into each other’s way.

J: I love that, particularly the nurse code leader element of cognitively offloading yourself. You have one point of contact, not trying to remember names, badges swept over in an unfamiliar environment. One point of contact, remember the one name, talk to that person and you’re offloaded in so many other ways. We’re prepping the room. Those ten minutes they gave us feel like two in terms of getting ready and we get a little more information about the patient, a 58-year-old gentleman battling with depression for a while and working with his primary care doctor and two or so weeks prior got started on antidepressants and unfortunately had that paradoxical worsening and after his wife had gone to bed that night, he went out to his woodshed, covered himself in gasoline and self-ignited. So, he comes flying through the door and looks absolutely horrible. The smell of burnt hair and flesh fills the room in a visceral sense. He’s covered in partial and full thickness burns at the head, neck, torso. He’s minimally responsive. EMS is bagging him, assisting his native respirations, and the vital signs come through as follows: heart rate in the 130’s; he did have a good blood pressure at 158/98; respirations were quick at 22; and was on the EMBU bag at 94%. So, I put him on oxygen and continued to assist with BVM. He doesn’t have that level of agitation or combativeness where I felt comfortable giving him 10mg of ketamine trying to take a look. He didn’t tolerate that, so we gave him another 10mg of ketamine and he allowed the CMAC to be passed. The view was kind of as expected: post pharynxes singed, edematous, markedly edematous cords with a very small opening. I’m able to get the bougie through that glottic opening that’s just pinpoint. I gave him rocuronium, which I think probably was a mistake, but we’ll dive into that more and tried to pass a 6-0 tube, tubal knockout, tried turning it, rotating it, all these positions and his O2 starts to go down. We’re able to take the bougie out and put it in LMA and he does bag with that, but it’s clear at this point the direction we’re going. This guy is going to need a cricothyrotomy. So, at that point, in this room filled with that horrific smell that’s relatively unfamiliar to me, I start to get this blackening in the periphery of my vision…

S: Before we get to this part because this is where the trauma and emotion really take place, you think we should talk about the stages up ‘til this moment of the decision to cric. So, you very appropriately get an awake look on this patient, got him in a good plane with the ketamine to be able to do that. You found a glottic opening that would fit a bougie, but would it fit any tube to be railroaded over that. A few things: If you can fit a bougie, you might be able to fit a pediatric tube in lieu of the bougie, but what some centers have and if you have them, you should know about it ahead of time, is they have tube exchangers…

J: I’m gonna say no. I didn’t ask for one, but let’s say probably not and not asked for.

S: If you did have them, what they provide is the capability of bagging or ventilating through them. They come with an adapter that takes the BDM. If you’re able to put that through, everything subsequent becomes a lot slower and easier to manage because you know you have something in the trachea that is going to allow you to continue to bag throughout. Many places don’t stock these. It’s a good thing to stock because it makes tube exchanges a lot safer. You didn’t have it, no worries. What was the thought of pushing the roc[uronium]?

J: Honestly, in retrospect, I have thought this over 100 times and it was a cognitive error. I had passed something through his glottic opening and almost rote, I think, in terms of access into the trachea and we move forward in that sequence. I think it was a complete cognitive error.

S: I hear you and I totally can sympathize with that. In general, obviously you’ve come to the same viewpoint, pushing rock or paralytics in these patients is not a great idea. They’re going to be much more capable of continuing spontaneous breathing through a small orifice than you guys are going to be doing by giving positive pressure from above. You were lucky, the LMA did allow continued ventilations, but not always the case, sometimes you get a collapse of what was a tenuous but still patent airway to now a non-patent airway, so leaving them awake in any circumstance of a marked anatomical difficult airway is the way to go in my opinion and doing an awake cric with a patient who is spontaneously breathing is a joy, it’s a real pleasure compared to when the clock starts ticking for an apneic (without breathing) apneic cric. You guys were lucky, able to bag through the LMA’s, still having a ventilated cric, safer way to go to just pull that bougie, put back on the high flow O2, then just make the decision which you made anyway, let’s just progress to a surgical airway because this is inevitable. This is not safe to leave them with this pinhole-sized opening for any period of time, but it does give us a nice, safe, calm cricothyrotomy. So that would be in retrospect a different way to play it that might be safer, but the chips are aligned where they may. It’s all good and now you’ve made the decision to do a surgical airway and you were about to tell me about the encroachment on your visual field by the fun little blackness of full-on stress overload.

J: I want to recognize that only Scott Weingart would call an awake cricothyrotomy an absolute joy, but I guess there’s some theory of relativity in that. The moment I made the decision is when I started to notice that my respirations were quite obvious, I could feel and hear my pulse in my ears, and it just started to creep in. Peripheral vision, a little bit worse, a little bit worse. I start to recognize, I’m overloaded. I’m overwhelmed with catecholamines right now, so I was wondering, Scott, walk us through what’s happening, how you approach it as an individual, and I’m very interested in how you teach residents to handle these types of incredibly rare and high acuity situations.

S: For all people at some point in their career, an innocuous thing is going to put them in the same degree of stress overload. It’s all relative depending on how often you’ve done what is expected of you and whether it’s a threat or challenge perception. For a first-year resident, putting an essential line in may put them in the same state of stress overload you were in with a burnt patient for cric, so there’s no shame wherever you’re at if you’re feeling this. It’s a normal thing. The tunneling you describe of peripheral vision loss, pulse overload, in essence self-induced apnea, you stop breathing and if you do breath, it’s dog panting and therefore has no actual gas exchange—all completely normal. What you need is in the moment stress relief and Mike Lauria and I put out a paper on this with a number of steps and since we wrote that paper I’ve mitigated and changed some of the ideas in there in what I teach. We used to teach square breathing where you breathe in for 4-5 seconds, you hold 4-5, then breathe out for the same. It works, makes you aware of your breathing, forcing you to take nice deep, slow breaths. What I actually find more effective in my own practice and there’s some literature outside of this realm to support it, is Vagal induction breathing and that’s about timing. You breathe in deep as you can, down into your belly all the way into your pelvis for four seconds, then force yourself with pursed lips to breathe out for six seconds. It’s that extended escalation time that actually starts countering the sympathetic surge and if you do two to three of those, you should feel some cessation of that stress. The other thing to do is get a handle on what your self-talk is telling you. If you have a critic in your brain telling you you’re going to fail, you messed up, how’d you get to this place where you needed the cric, means you’re an idiot at airway management. You’ve got to shut that voice up and say, “This was an inevitable surgical airway and I’m absolutely up to the task of getting this job done. I’ve trained on this on models and I know I can do this and that positive self-talk will absolutely help if you have a negative critic. I like to recommend that people find their feet. If you can’t find your feet, meaning you say where are my feet and have no idea, can’t have any perception of the actual feedback of your feet on the floor, that means spend five seconds on finding your feet again and just like the breathing control, will change your brain’s reaction to stress. If you find your feet and control your breathing, and get your self-talk under control, within 10-20 seconds you should have mitigated, not eliminated, the stress overload.

J: I love that. There’s so much to unpackage there. Square breathing, I teach that to people who come in for panic all the time, I used that in this circumstance. And then self-talk, I believe you use a specific phraswe yourself, “Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast,” in terms of trying to calm oneself down and feel in control. I have actually not adopted that. I suffer from a little imposter syndrome and I kind of just hear you saying that in my head. I need my own term. Relax, you got this, you’re in control.

S: It’s funny. You’ve blended two things and I think blending is fine, but there’s positive self-talk that I alluded to and then there’s what you alluded to, a mantra that sets off pre-set feelings within yourself. The “Slow is Smooth, Smooth is Fast” is what we call a power phrase, or mantra, you see various things in the literature on that and that’s something you should build ahead of time with whatever relaxation process you do, you associate it with that phrase so it becomes a Pavlovian linking of that in your mind and that can be helpful even when you’re not in stress overload. Any resuscitation situation. It’s from the military and that mantra is connected to a state of relaxation, well being and capability, while self-talk is when you’ve already surpassed the pre-stage and your imposter syndrome voice is telling you bad things and then whatever internal verbalizations mitigate it for you, great. If you’re hearing me say, You got it man,” I’m happy to be serving that role and by all means, whatever works to counter the inner critics.

J: I appreciate the no charge and free service there. I like the idea of both the mantra and then in high stakes circumstances, any positive self-talk that works for you. I want to dive a little bit more into that breathing. I think that’s interesting, the idea of a pursed lip exhalation, are you trying to valsalva and create a Vagal response to lower your own heart rate?

S: Val salva is dangerous, you might pass out in these circumstances. You are trying to get a Vagal response and this is real. In fact, entire heartrate variability studies on this exact thing, a market of how de-stressed you are and this is the breathing form…everyone has their own internal rhythm, but you won’t know yours until you work with a heartrate monitor, actually a great practice, I recommend it. Not going to have that in the moment, so four and six work nicely for you and, yes, what you’re trying to do is Vagal countering of that excess sympathetic surge.

J: Fantastic. I’m going to start practicing that with a heartrate monitor, that would be cool.

S: If you have anything you use for tracking fitness, then there’s a bunch of free or incredibly cheap iPhone apps that will tell you your heartrate variability and what you try to find is the inhalation-exhalation match that gives you the greatest heartrate variability and once you have that number, it’s yours forever.

J: Find your feet, that’s fantastic, literally grounding yourself. In those environments you kind of feel like you’re floating in the air or underwater, but looking down and feeling your feet on the ground, what a simple and powerful way to connect yourself and ground yourself in your environment.

S: Worthwhile to have body awareness as a meditation. It’s directly applicable to stress.

J: You ready to dive into how I went through the cric?

S: Let’s preface with: Any successful cric is the right cric, so if you got an airway on that patient, it was a huge win.

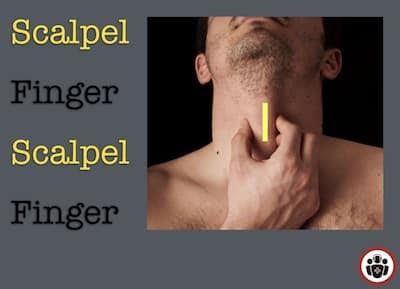

J: Spoiler alert, yes I succeeded, and the team was able to pull through, but in walking through the steps of it, we placed an LMA and we’re lucky through that very small aperture to be able to re-ox him, get him back up to a good number where I felt comfortable. I put two CC’s of my concoction I had created earlier into my target area after I did the laryngeal handshake, but that neck was badly burned, difficult to feel through this leathery, endemitous and tight skin, but I was able to find the area I thought I was going to be going after. Did my vertical incision and there was very little blood probably because of that burn the patient had. The nurse actually used suction for taking away that beta blood, which I thought was nice, but probably not vital to the success of what is a blind procedure after your first incision, but I went through and did my horizontal stab and in retrospect I don’t know if I went scalpel-finger-bougie. I think I went scalpel to bougie but the bougie thread with tactile confirmation of the trachea put a 6-02 over that, pretty sure I right-main set him because my general was through the roof at 11, so we pulled it back, put on one of those sticky tube holder things we often use, and successfully cric-ed the individual. In recounting that, Scott, how’d I do? What kind of tips do you have, what would you keep, what would you change in terms of that process?

S: Let me reiterate what I said in the beginning is that if you get it successfully somewhere in the trachea, I don’t care how it gets there, that is a win on the cric. Everything else is just fine points here. You had prefaced with getting the room set up, was that what you actually used? For most patients if I have to get something prepped ahead of time, it’s going to be a template. A template is going to give you a lot more options, going to make it a lot easier, and if you use the technique you actually wound up using, which is not putting a finger through the cricothyroid membrane, then the template is intrinsically dilating as opposed to when it’s too thin and you might have to push a little bit harder than you want. If you have the time to figure out, let’s get ready for a cric on this patient as opposed to, “Please, hand me a scalpel,” then a tan is a nice one to prep and especially on a patient with the S-car, cutting through that stuff with a 10 blade is a little bit easier, but there’s nothing wrong with it and the techniques I teach are blade agnostic.

J: Does your stab work just as well with the 10? That’s why I chose the 11, I suppose.

S: When I teach 11 blade or blade agnostic for cricothyrotomy, I require people to make a stab incision with the 11 blade all the way toward them, flip the blade 180 degrees and push away so you’re cutting the full extent of the cricothyroid membrane, which allows you to get away with the smaller size of the 11 blade, and allows you to remove the blade entirely and stick your finger in there. If you want to use the technique, and it’s an adequate technique, of stabbing and then placing a bougie next to it, really benefits from a 10 blade which is big enough to make the incision, then ideally rotate that 10 blade 90 degrees so the blade faces the patient’s feet, then run the bougie along the flat portion of the blade rather than the blade itself. You probably did this intrinsically and even if you did, it was your work, but it’s harder when you don’t make that 90-degree turn. I want to come back to the yankauer, now this nurse was being helpful and you have to applaud the intent and the forethought of this nurse saying, “There’s going to be bleeding, let me help out,” and it’s fine, it’s not going to do any harm as long as it’s not getting in your way, but it does again put a cognitive barrier to what has to happen, might click you into the mode of “She’s suctioning and now I have a big puddle of blood, let me have them suction again to get that puddle of blood out before I start making my plunge incision. You want to get out of that mindset, you want to say just as you did, this is a blind procedure, so you don’t need to suction for me. Because I think it’s going to send me down the wrong mental path. It’s a fully tactile procedure after the initial skin incision, so it doesn’t matter to me whether there’s bleeding and if I can see or not and even if it’s spurting blood and people think they hit the carotid, you didn’t, probably just hit a superficial artery, but they’ll get scared and try to get hemostasis before they have the airway in. First of all, putting the airway in tamponades everything down quite nicely, so that should take care of the bleeding, but even if it doesn’t, they will not exsanguinate before they die from lack of an ET tube, so the move is always no matter how much the bleeding is, even if you did hit a branch of the innominate [artery] and it really is a mass exsanguination, is to finish the cric. Then, no matter what you hit, it’s amenable to direct pressure so I don’t want suction…

J: Yeah, you get a pumper, that’s going to add a little more of that stress inoculation and make you think, “I’ve done something wrong, I need to fix that,” we see a problem we try to fix it quickly but recognizing they’re more rapidly going to die from their hypoxia than they are from even a decent pumper. You can get that airway and then fix the bleed. So, this case for me was a perfect storm of all the things you don’t really want as a physician. I was a young doctor with a team I wasn’t very familiar with, had two prior shifts, but many of the nurses were different, the environment was unfamiliar, I was two years out from residency and hadn’t practiced cricothyrotomy in that time, about 2.5 years. So, some of those elements are controllable, some of course are not. Scott, what would you recommend to the audience when it comes to high acuity low opportunity (HALO) procedures and maintaining yourself as an individual and your team in preparedness.

S: Let’s use cric as an example since it’s so pertinent to what we’ve been discussing today. This is the ultimate HALO procedure. You need to know how to do this, but you might do one in your career unless you’re an idiot like me. You should train on this. Now, luckily, for cric in contrast to many procedures, test trainers are enough, and my buddy Laura Duggan took a common source model and made a 3-D schematic and print one up and that plastic model with some 4×4’s and a plastic bag is enough to be absolutely ready for real life. I’ve had like 38 people email me after doing one of my courses where they had no pigs, no human models, just this plastic test trainer and then did their first cric, said it was completely like the test trainer, absolutely fine, no problem doing that translation, so this means you don’t need to be in a sim lab, you don’t need extensive equipment. What you do need to do is actually force yourself to practice this on a regular basis. My buddy Sarah Gray has on her calendar, every three months, practice cric. It’s on her calendar so she does it, gets out test trainer, grabs some 4×4’s and plastic bags from her department, and just goes through ten of these crics, takes less than 10 minutes, then she’ll do it again. She might do it more frequently. If there’s 12 procedures HALO in your world, put one a month on your calendar and just do them. It might be mental visualization. If you don’t have a test trainer, might be something like Minnesota tube or a Blakemore, or maybe it just means you go in for your shift 10 minutes early, open up the Blakemore, you don’t ruin it, don’t get it unsterile, but look at it and say what additional equipment do I need, how would I actually get that done?

J: I like that you bring up the mental aspect because like you said, resuscitative hysterotomy, you’re not going to be able to reproduce that in any meaningful way probably, but at least taking the procedure out and dusting it off physically or mentally at regular intervals, that’s a good idea. How about in terms of team? Does Sarah do this with her charge nurses or other members of the team?

S: They’re at their shop in Canada and they’re simming out the wazoo things like nurse code for cardiac arrest, management of heavy traumas, doing sim scenarios all the time. If you’re at a community shop where you don’t have that culture of giving free time for people to play on these sims, when you have to pare it down a little bit, no reason you can’t get everyone on board once a month to do a sim for ten minutes during a quiet time and pick out a scenario that is rare, but yet you still want people to trained to do. All the sudden a patient rolls in with a massive exsanguination from trauma, let’s run through it. You don’t have to open up equipment, let’s table top it. We need a massive transfusion, how do we get that done? We forgot. Okay, let’s review it during the debrief of the case, how that works and let’s work it out. It might just be there’s only four units of blood in the entire hospital and we use PCC. Okay, fine, let’s work that out. Where’s the pelvic binder? We don’t stock a pelvic binder, we use sheets. Do people remember how to do pelvic binding with sheets? No, we don’t. Okay, let’s review that and mark down to send out an education brief on how to do it. That kind of stuff can be with no money, very little time, and yet makes everyone love the person orchestrating that, everyone loves it, so much fun, and affects your ability to be ready for these patients.

J: I love that and think it’s a great idea in terms of working as a team and in our particular environment now with the turnover we’ve seen in healthcare, a lot of us are working with nurses we’re not familiar with, travel nurses, and if you get that team on board, you’re going to find holes that really shouldn’t be there. While ideal to have it at a time that’s organized and scheduled, I’m finding myself on overnights when it’s not crazy, few and far between, get the group together and walk through some of these cases mentally. It’s beneficial in any capacity.

Back to case, patient handles cric well, get him on the vent, begin fluid resuscitation using LR for the Parkland formula. He’s incredibly badly burned, it’s a large volume of resuscitation, call the trauma center who accepts him, and we’re letting the dust settle. I come up to him and realize he has this leather-type sensation to the chest. The idea of how he is going to do on this ventilator with that degree of burning certainly came to my mind. Unfortunately, a lot of references out there about escharotomy talk about if it inhibits adequate respiration or if there’s respiratory compromise related to the circumferential burns, that’s very vague and not very practical to me, so how do you know when a patient like this needs an escharotomy and also what’s the timing for that?

S: You’re going to know because you’re going to start getting pressure alarms on your vent if you’re in volume control mode which is what I think most emergency department physicians use. You’ll start getting peak pressure alarms and that’s going to tell you you’re not getting in those breaths because it can’t exceed the pressure that chest wall is exerting. If you’re in pressure control mode, you start noticing your title volumes diminishing and that’s really the time for emergency medicine to be considering this. Vent will keep alarming, going to be the S-Car at that point. You look down at the chest at that point and they’re just not expanding their chest wall. We might be doing it earlier in a burn ICU, might say screw it, we know they’re going to progress to this, but for an M.D. that doesn’t want to do this if they don’t have to, that’s when you’re not getting full breaths in on the ventilator and so not safe to transport or safe to wait around.

J: What I recollect of the case in talking with our trauma surgeon, we asked specifically about this and he set the number at 40, if he’s starting to alarm or getting peak pressure at 40, that’s not good, having restriction in terms of lung expansion and that’s when you would consider doing the procedure.

S: It’s somewhere between 40-50 and you’re not going to get this number because the respiratory therapist usually sets it between 40-50. It’s going to work out well for you regardless of where you’re at. The peak pressure line generally gets set about 10-20 above maximum plateau which is 30, so they’ll set it at 40-50 and when the alarm goes off, you know you have a problem.

J: That’s easy. Things start alarming, we know we have a problem, must start cutting. Luckily for the patient, those alarms did not occur. There was a delay in transportation, hard time finding an ambulance ventilator, so had a longer stay in our ER, but we continued resuscitation, the dust settled, and we were eventually allowed to high five one another and the patient made it out of the department safely. Worked through a very challenging case for me. Really, Scott, appreciate you so much for coming on, talking through not only the mechanics of doing cricothyrotomy, but also that stress mitigation in the moment. Thanks so much for your insights and talking through this case. It was kind of a practice-changing case for me.

S: So great to catch up with you, man.

J: ‘Til next time. Everybody thanks for listening and we’ll talk to you soon.

Practicing procedures can be tough. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting in your skill maintenance. Procedural training can and should be easy, done in your home or department, and work within your schedule. We want you to be confident and competent clinicians, and we have the tools to help.