Transvenous Pacing Procedure

Procedure Video

A. Indications

Hemodynamically compromising dysrhythmias that are unresponsive to medical therapy and are amenable to pacing. It is important to note that many dysrhythmias that cause hemodynamic compromise are not responsive to transcutaneous or transvenous pacing. Ones that are include:

a. Bradydysrhythmias – Sinus node dysfunction, for example from an inferior myocardial infarction, is a common cause to hemodynamic collapse that is responsive to pacing. Others include SA node dysfunctions such as unstable 2nd degree and 3rd degree heart blocks. Again, medical therapy should be considered first, especially for the sinus node dysfunction.

b. Tachydysrhythmias – Pacing in tachydysrhythmias works by the “overdrive” effect, pacing at a rate faster than the underlying rhythm then gradually slowing the rate. It is important to note that many tachydysrhythmias will respond to medical therapy or cardioversion.

Note: Transcutaneous pacing is advisable if a readily reversible cause of dysrhythmia is expected. Prolonged transcutaneous pacing is an indication for conversion to transvenous. In most circumstances, when transvenous pacing is being established transcutaneous pacing should already be underway.

B. Contraindications

Few absolute contraindications exist for transvenous pacing. Most contraindications revolve around alternative therapies.

a. Mechanical tricuspid valve is a true contraindication.[1]

b. Hypothermia: Given the nature of dysrhythmias in hypothermia and their propensity to deteriorate with pacer wire placement, rapid rewarming is recommended first. If the condition does not improve when the patient is normothermic, pacing should then be considered.

c. Drug-induced dysrhythmia: Given the injury in poisoning or drug-induced dysrhythmia is at the cellular level, pacing is rarely beneficial and is a relative contraindication.[1]

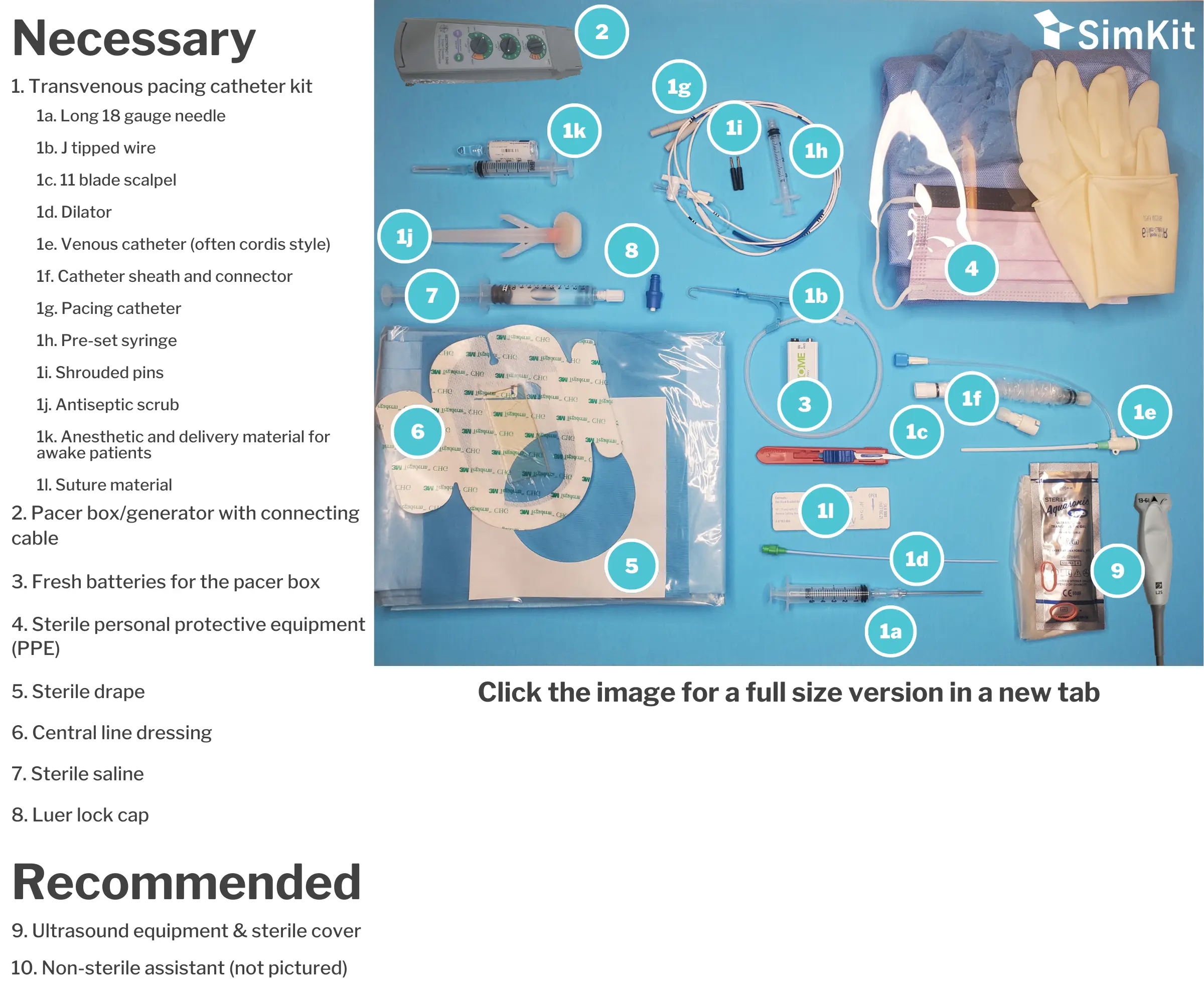

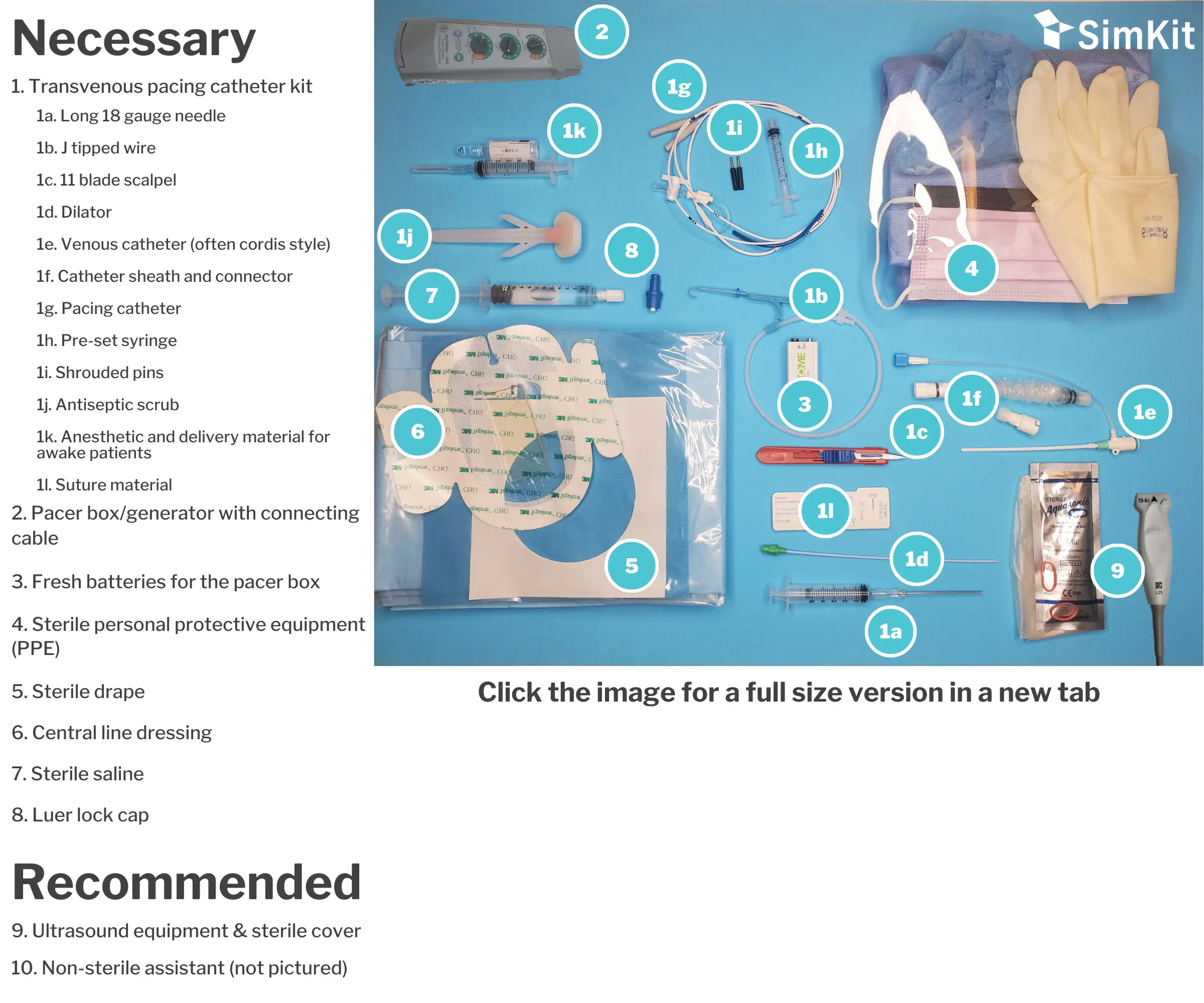

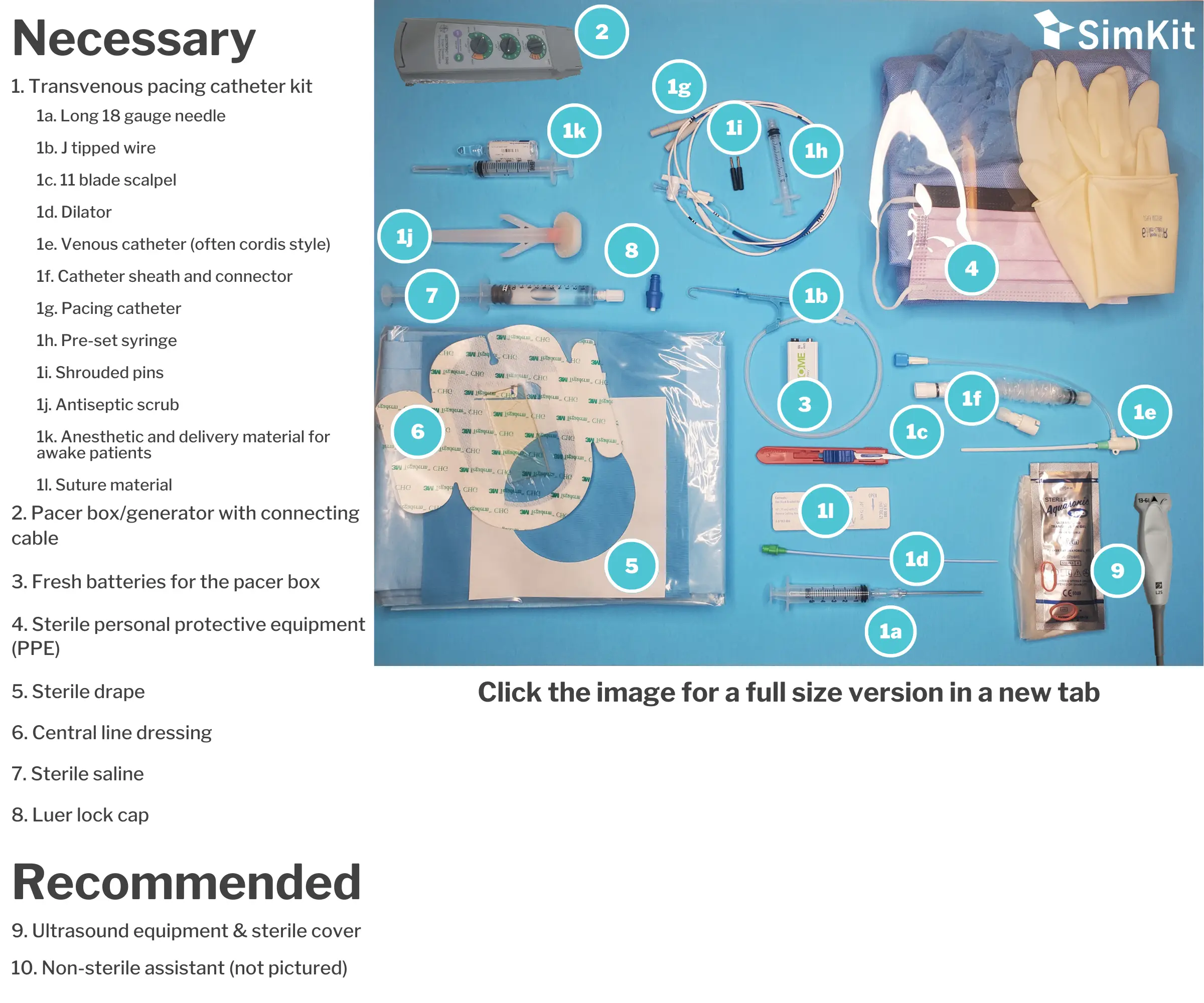

C. Materials

D. Steps

This procedure is done under sterile conditions following central venous catheter placement best practices.

Step 1 | Turn on pacer, put in settings

There are two ways to set your pacer- to sensing or to pacing. In these emergent situations, and for simplicity, it is recommended to go in pacing. To do this, set the rate you want on the pacer (usually 20 bpm above the intrinsic or transcutaneous pacer rate, or 80 bpm). Set your sensitivity so that the pacer will fire no matter the intrinsic rhythm – this means turn the sensitivity all the way UP or ideally your box has an asynchronous mode you can set it to. Then set the output. Many sources recommend a 5-10 mA start[1], but for simplicity we recommended the highest setting, 20 mA to guarantee capture. You can adjust down from there.

Note: Most pacers will have an asynchronous mode, which we will utilize in these emergent situations. In asynchronous mode you can set the rate but the output and sensitivity will be preselected.

Step 2 | Go sterile, test balloon, place pins and sleeve

After donning a cap, face mask, sterile gown and gloves, unpackage the pacer catheter. Some kits will have a plastic sleeve to protect the catheter tip and give it a slight curve. Remove this and find the pre-set volume syringe (1.5 cc) used to inflate the balloon. Attach this to the stopcock at the distal end of the catheter and use it to test balloon integrity. Lock the stopcock to verify function, then deflate balloon. There are two sterile pins that go into the distal end of the catheter, insert these now. Before inserting the catheter, it is crucial to slide on the catheter sheath and connector from the pacing kit. Do this now. This allows adjustment of catheter tip depth after the procedure is completed without losing sterility.

Tip: As seen in step 5, the distance to exit the introducer is important. An additional step that can be taken is to remove the dilator from the introducer, attach the sterile sleeve, and thread the catheter in (with the balloon deflated). Note which black tick mark lines (each representing 10 cm so one line is 10 cm, two lines 20 cm, etc.) you approach when the catheter tip and balloon clear the introducer. You will need to make sure you clear this distance before balloon inflation.

Step 3 | Gain access

The pacing kit contains an introducer similar to a cordis central line. This must be flushed before starting like a standard central line. Using sterile technique, gain access to a central vein (right internal jugular or left subclavian recommended), preferably with US guidance to decrease complications. Use standard Seldinger technique for this. Once the introducer is placed remove the internal obturator/dilator.[1] Secure the line to the skin.

Step 4 | Place the catheter

Thread the pacing catheter through the sterile sleeve and introducer. Again, pay careful attention to the black markings on the catheter. Each of these indicate 10 cm. In most systems, the catheter tip and balloon will safely exit the introducer at 15 cm. You can use 20 cm (two black lines) to be safe. Then inflate the balloon and lock the stopcock.

Step 5 | Connect to the cable

Have your nonsterile assistant hold the connecting cable while you carefully insert the pins at the distal end of the catheter into their appropriate port. Note P is for Positive and Proximal. Insert pin labeled P into the POSITIVE port. Inset pin labeled D (distal) into the NEGATIVE port.

Step 6 | Get capture

Quickly advance the catheter. Watch your catheter and patient while the non-sterile assistant watches the monitor for an increase in heart rate to your box’s set rate. At this point you can deflate your balloon, lock the stopcock and remove the 1.5 cc syringe.

Tip: There is a difference between electrical and mechanical capture. Once capture is seen on telemetry, check your pulse oximeter’s waveform, which will show mechanical capture as measured at the site the pulse ox is located (usually finger). US assessment of catheter location in the right ventricle should also be considered. If using electrocargiographic confirmation, look for a right bundle branch block pattern on telemetry to verify paced beats.

Step 7 | Decrease output

Decrease output: Slowly turn down the output amperage until you lose capture, then turn it back up to capture and add an additional 2-3 mA for assurance.

Step 8 | Extend sterile sleeve

After completing the procedure you can extend the sterile sleeve to allow for later manipulation. Place a sterile central line cover over your insertion site.

References

[1] Bessman E. (2017). ‘Emergency Cardiac Pacing” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Elsevier. Pp. 277-297.

Transvenous Pacing Procedure

Welcome to the Transvenous Pacing procedure page. Here we will cover indications, contraindications, materials and steps for you to master this procedure. Let’s begin below with the procedure video.

Procedure Video

A. Indications

Hemodynamically compromising dysrhythmias that are unresponsive to medical therapy and are amenable to pacing. It is important to note that many dysrhythmias that cause hemodynamic compromise are not responsive to transcutaneous or transvenous pacing. Ones that are include:

a. Bradydysrhythmias – Sinus node dysfunction, for example from an inferior myocardial infarction, is a common cause to hemodynamic collapse that is responsive to pacing. Others include SA node dysfunctions such as unstable 2nd degree and 3rd degree heart blocks. Again, medical therapy should be considered first, especially for the sinus node dysfunction.

b. Tachydysrhythmias – Pacing in tachydysrhythmias works by the “overdrive” effect, pacing at a rate faster than the underlying rhythm then gradually slowing the rate. It is important to note that many tachydysrhythmias will respond to medical therapy or cardioversion.

Note: Transcutaneous pacing is advisable if a readily reversible cause of dysrhythmia is expected. Prolonged transcutaneous pacing is an indication for conversion to transvenous. In most circumstances, when transvenous pacing is being established transcutaneous pacing should already be underway.

B. Contraindications

Few absolute contraindications exist for transvenous pacing. Most contraindications revolve around alternative therapies.

a. Mechanical tricuspid valve is a true contraindication.[1]

b. Hypothermia: Given the nature of dysrhythmias in hypothermia and their propensity to deteriorate with pacer wire placement, rapid rewarming is recommended first. If the condition does not improve when the patient is normothermic, pacing should then be considered.

c. Drug-induced dysrhythmia: Given the injury in poisoning or drug-induced dysrhythmia is at the cellular level, pacing is rarely beneficial and is a relative contraindication.[1]

C. Materials

D. Steps

This procedure is done under sterile conditions following central venous catheter placement best practices.

Step 1 | Turn on pacer, put in settings

There are two ways to set your pacer- to sensing or to pacing. In these emergent situations, and for simplicity, it is recommended to go in pacing. To do this, set the rate you want on the pacer (usually 20 bpm above the intrinsic or transcutaneous pacer rate, or 80 bpm). Set your sensitivity so that the pacer will fire no matter the intrinsic rhythm – this means turn the sensitivity all the way UP or ideally your box has an asynchronous mode you can set it to. Then set the output. Many sources recommend a 5-10 mA start[1], but for simplicity we recommended the highest setting, 20 mA to guarantee capture. You can adjust down from there.

Note: Most pacers will have an asynchronous mode, which we will utilize in these emergent situations. In asynchronous mode you can set the rate but the output and sensitivity will be preselected.

Step 2 | Go sterile, test balloon, place pins and sleeve

After donning a cap, face mask, sterile gown and gloves, unpackage the pacer catheter. Some kits will have a plastic sleeve to protect the catheter tip and give it a slight curve. Remove this and find the pre-set volume syringe (1.5 cc) used to inflate the balloon. Attach this to the stopcock at the distal end of the catheter and use it to test balloon integrity. Lock the stopcock to verify function, then deflate balloon. There are two sterile pins that go into the distal end of the catheter, insert these now. Before inserting the catheter, it is crucial to slide on the catheter sheath and connector from the pacing kit. Do this now. This allows adjustment of catheter tip depth after the procedure is completed without losing sterility.

Tip: As seen in step 5, the distance to exit the introducer is important. An additional step that can be taken is to remove the dilator from the introducer, attach the sterile sleeve, and thread the catheter in (with the balloon deflated). Note which black tick mark lines (each representing 10 cm so one line is 10 cm, two lines 20 cm, etc.) you approach when the catheter tip and balloon clear the introducer. You will need to make sure you clear this distance before balloon inflation.

Step 3 | Gain access

The pacing kit contains an introducer similar to a cordis central line. This must be flushed before starting like a standard central line. Using sterile technique, gain access to a central vein (right internal jugular or left subclavian recommended), preferably with US guidance to decrease complications. Use standard Seldinger technique for this. Once the introducer is placed remove the internal obturator/dilator.[1] Secure the line to the skin.

Step 4 | Place the catheter

Thread the pacing catheter through the sterile sleeve and introducer. Again, pay careful attention to the black markings on the catheter. Each of these indicate 10 cm. In most systems, the catheter tip and balloon will safely exit the introducer at 15 cm. You can use 20 cm (two black lines) to be safe. Then inflate the balloon and lock the stopcock.

Step 5 | Connect to the cable

Have your nonsterile assistant hold the connecting cable while you carefully insert the pins at the distal end of the catheter into their appropriate port. Note P is for Positive and Proximal. Insert pin labeled P into the POSITIVE port. Inset pin labeled D (distal) into the NEGATIVE port.

Step 6 | Get capture

Quickly advance the catheter. Watch your catheter and patient while the non-sterile assistant watches the monitor for an increase in heart rate to your box’s set rate. At this point you can deflate your balloon, lock the stopcock and remove the 1.5 cc syringe.

Tip: There is a difference between electrical and mechanical capture. Once capture is seen on telemetry, check your pulse oximeter’s waveform, which will show mechanical capture as measured at the site the pulse ox is located (usually finger). US assessment of catheter location in the right ventricle should also be considered. If using electrocargiographic confirmation, look for a right bundle branch block pattern on telemetry to verify paced beats.

Step 7 | Decrease output

Decrease output: Slowly turn down the output amperage until you lose capture, then turn it back up to capture and add an additional 2-3 mA for assurance.

Step 8 | Extend sterile sleeve

After completing the procedure you can extend the sterile sleeve to allow for later manipulation. Place a sterile central line cover over your insertion site.

References

[1] Bessman E. (2017). ‘Emergency Cardiac Pacing” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Elsevier. Pp. 277-297.

Transvenous Pacing Procedure

Welcome to the Transvenous Pacing procedure page. Here we will cover indications, contraindications, materials and steps for you to master this procedure. Let’s begin below with the procedure video.

Procedure Video

A. Indications

Hemodynamically compromising dysrhythmias that are unresponsive to medical therapy and are amenable to pacing. It is important to note that many dysrhythmias that cause hemodynamic compromise are not responsive to transcutaneous or transvenous pacing. Ones that are include:

a. Bradydysrhythmias – Sinus node dysfunction, for example from an inferior myocardial infarction, is a common cause to hemodynamic collapse that is responsive to pacing. Others include SA node dysfunctions such as unstable 2nd degree and 3rd degree heart blocks. Again, medical therapy should be considered first, especially for the sinus node dysfunction.

b. Tachydysrhythmias – Pacing in tachydysrhythmias works by the “overdrive” effect, pacing at a rate faster than the underlying rhythm then gradually slowing the rate. It is important to note that many tachydysrhythmias will respond to medical therapy or cardioversion.

Note: Transcutaneous pacing is advisable if a readily reversible cause of dysrhythmia is expected. Prolonged transcutaneous pacing is an indication for conversion to transvenous. In most circumstances, when transvenous pacing is being established transcutaneous pacing should already be underway.

B. Contraindications

Few absolute contraindications exist for transvenous pacing. Most contraindications revolve around alternative therapies.

a. Mechanical tricuspid valve is a true contraindication.[1]

b. Hypothermia: Given the nature of dysrhythmias in hypothermia and their propensity to deteriorate with pacer wire placement, rapid rewarming is recommended first. If the condition does not improve when the patient is normothermic, pacing should then be considered.

c. Drug-induced dysrhythmia: Given the injury in poisoning or drug-induced dysrhythmia is at the cellular level, pacing is rarely beneficial and is a relative contraindication.[1]

C. Materials

D. Steps

This procedure is done under sterile conditions following central venous catheter placement best practices.

Step 1 | Turn on pacer, put in settings

There are two ways to set your pacer- to sensing or to pacing. In these emergent situations, and for simplicity, it is recommended to go in pacing. To do this, set the rate you want on the pacer (usually 20 bpm above the intrinsic or transcutaneous pacer rate, or 80 bpm). Set your sensitivity so that the pacer will fire no matter the intrinsic rhythm – this means turn the sensitivity all the way UP or ideally your box has an asynchronous mode you can set it to. Then set the output. Many sources recommend a 5-10 mA start[1], but for simplicity we recommended the highest setting, 20 mA to guarantee capture. You can adjust down from there.

Note: Most pacers will have an asynchronous mode, which we will utilize in these emergent situations. In asynchronous mode you can set the rate but the output and sensitivity will be preselected.

Step 2 | Go sterile, test balloon, place pins and sleeve

After donning a cap, face mask, sterile gown and gloves, unpackage the pacer catheter. Some kits will have a plastic sleeve to protect the catheter tip and give it a slight curve. Remove this and find the pre-set volume syringe (1.5 cc) used to inflate the balloon. Attach this to the stopcock at the distal end of the catheter and use it to test balloon integrity. Lock the stopcock to verify function, then deflate balloon. There are two sterile pins that go into the distal end of the catheter, insert these now. Before inserting the catheter, it is crucial to slide on the catheter sheath and connector from the pacing kit. Do this now. This allows adjustment of catheter tip depth after the procedure is completed without losing sterility.

Tip: As seen in step 5, the distance to exit the introducer is important. An additional step that can be taken is to remove the dilator from the introducer, attach the sterile sleeve, and thread the catheter in (with the balloon deflated). Note which black tick mark lines (each representing 10 cm so one line is 10 cm, two lines 20 cm, etc.) you approach when the catheter tip and balloon clear the introducer. You will need to make sure you clear this distance before balloon inflation.

Step 3 | Gain access

The pacing kit contains an introducer similar to a cordis central line. This must be flushed before starting like a standard central line. Using sterile technique, gain access to a central vein (right internal jugular or left subclavian recommended), preferably with US guidance to decrease complications. Use standard Seldinger technique for this. Once the introducer is placed remove the internal obturator/dilator.[1] Secure the line to the skin.

Step 4 | Place the catheter

Thread the pacing catheter through the sterile sleeve and introducer. Again, pay careful attention to the black markings on the catheter. Each of these indicate 10 cm. In most systems, the catheter tip and balloon will safely exit the introducer at 15 cm. You can use 20 cm (two black lines) to be safe. Then inflate the balloon and lock the stopcock.

Step 5 | Connect to the cable

Have your nonsterile assistant hold the connecting cable while you carefully insert the pins at the distal end of the catheter into their appropriate port. Note P is for Positive and Proximal. Insert pin labeled P into the POSITIVE port. Inset pin labeled D (distal) into the NEGATIVE port.

Step 6 | Get capture

Quickly advance the catheter. Watch your catheter and patient while the non-sterile assistant watches the monitor for an increase in heart rate to your box’s set rate. At this point you can deflate your balloon, lock the stopcock and remove the 1.5 cc syringe.

Tip: There is a difference between electrical and mechanical capture. Once capture is seen on telemetry, check your pulse oximeter’s waveform, which will show mechanical capture as measured at the site the pulse ox is located (usually finger). US assessment of catheter location in the right ventricle should also be considered. If using electrocargiographic confirmation, look for a right bundle branch block pattern on telemetry to verify paced beats.

Step 7 | Decrease output

Decrease output: Slowly turn down the output amperage until you lose capture, then turn it back up to capture and add an additional 2-3 mA for assurance.

Step 8 | Extend sterile sleeve

After completing the procedure you can extend the sterile sleeve to allow for later manipulation. Place a sterile central line cover over your insertion site.

Reference

[1] Bessman E. (2017). ‘Emergency Cardiac Pacing” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care.