Lateral Canthotomy Procedure

Procedure Video

A. Indications

The indication for this procedure are signs and symptoms of acute orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). The most common cause of acute orbital compartment syndrome is trauma leading to retrobulbar hematoma.[1] Other traumatic causes include intraocular hematoma, subperiosteal hematoma, and sinus fractures with orbital emphysema. Outside of trauma, the most common causes of OCS are facial surgery and orbital cellulitis.[2][3]

It is important to recognize acute OCS is a clinical diagnosis. The symptoms include ocular pain, limited eye movement, and visual impairment. The associated signs are proptosis, decreased visual acuity in the affected eye, limited extraocular movement, afferent pupillary defect, and increased intraocular pressure (IOP). If measured, a soft cut point for IOP is >40 mmHg as an indication for decompression.

Acute OCS is a time sensitive emergency, and therefore imaging should not delay treatment, unless more significant life threats (intracranial hemorrhage etc.) require rule out first, which is often the case in these traumatic cases. In these instances, the retrobulbar hematoma is often then seen. Other findings that suggest OCS include proptosis, afferent pupil defect and, in the alert patient, decreased visual acuity.[4] While >40 mmHg IOP is the textbook answer for this procedure, patient presentation and characteristics must be considered. In the right patient (for example: retrobulbar hematoma, proptosis, significantly reduced visual acuity), lateral canthotomy may be indicated despite IOPs below 40 mmHg.

Note: The procedure is technically a combination of a lateral canthotomy and inferior (+/- superior) cantholysis.

B. Contraindications

Globe rupture is the only absolute contraindication to lateral canthotomy. This can be diagnosed clinically or by advanced imaging (CT). Alternative causes for high intraocular pressure (acute angle closure glaucoma) should be ruled out before lateral canthotomy is performed.

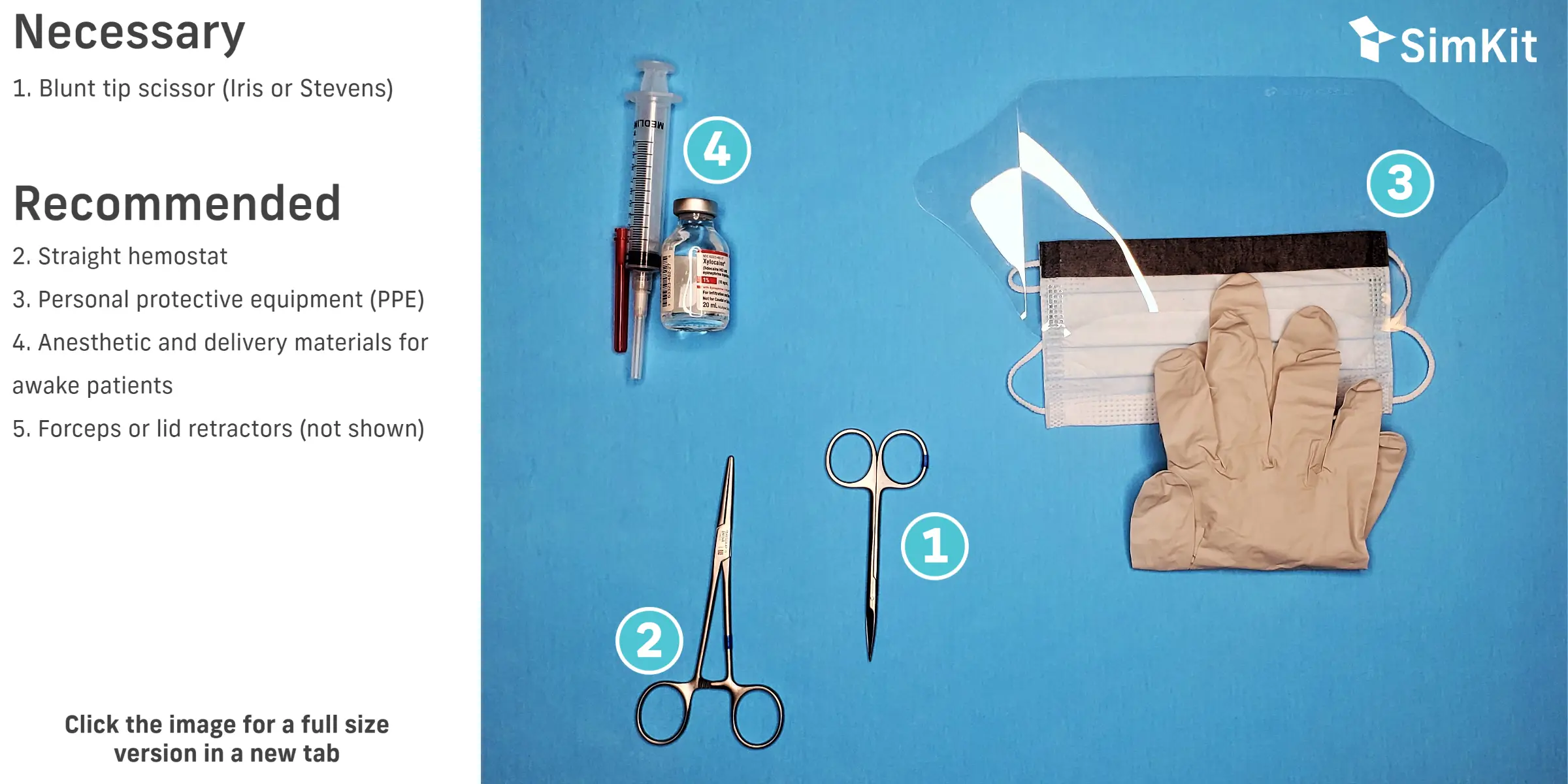

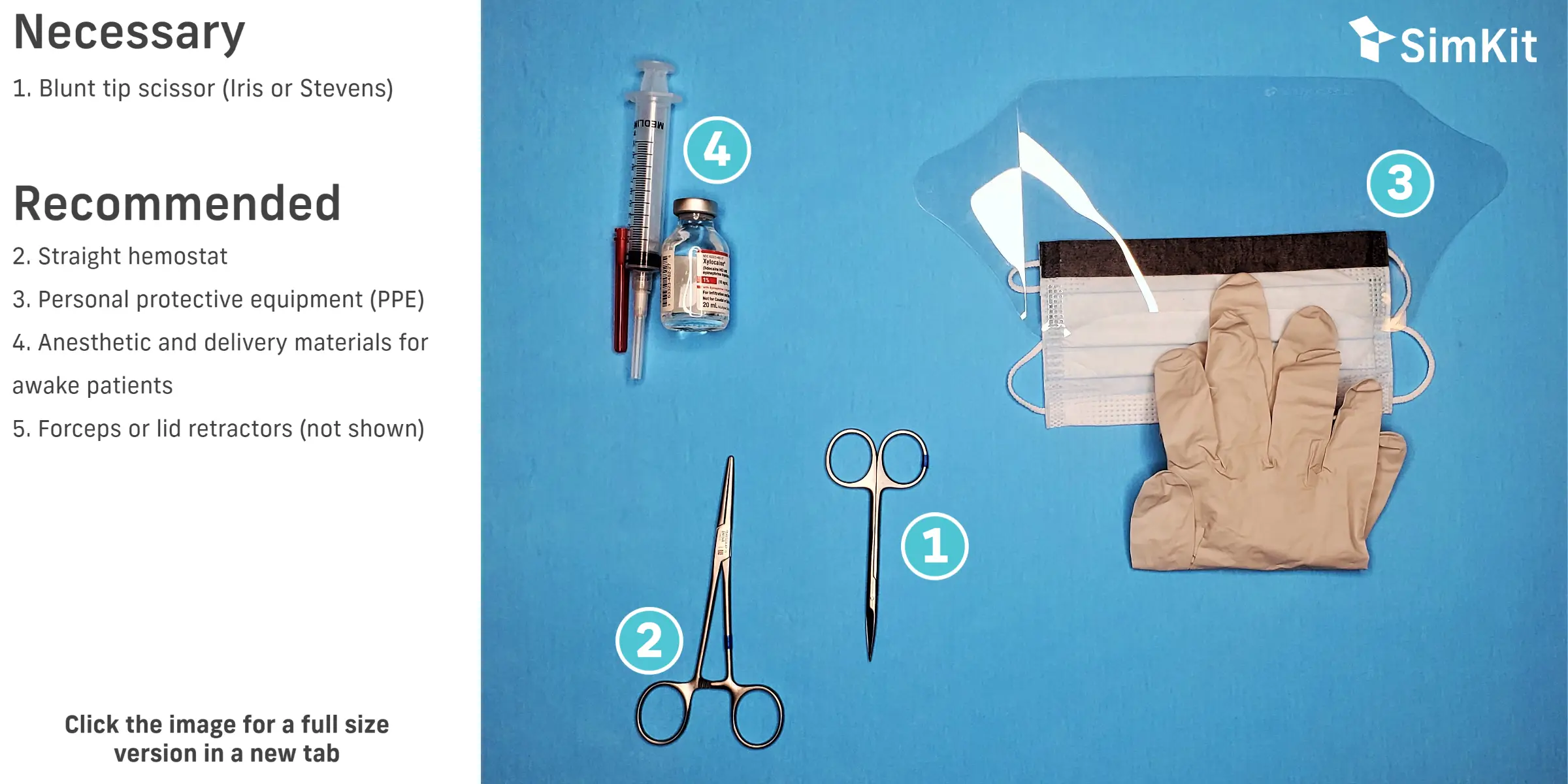

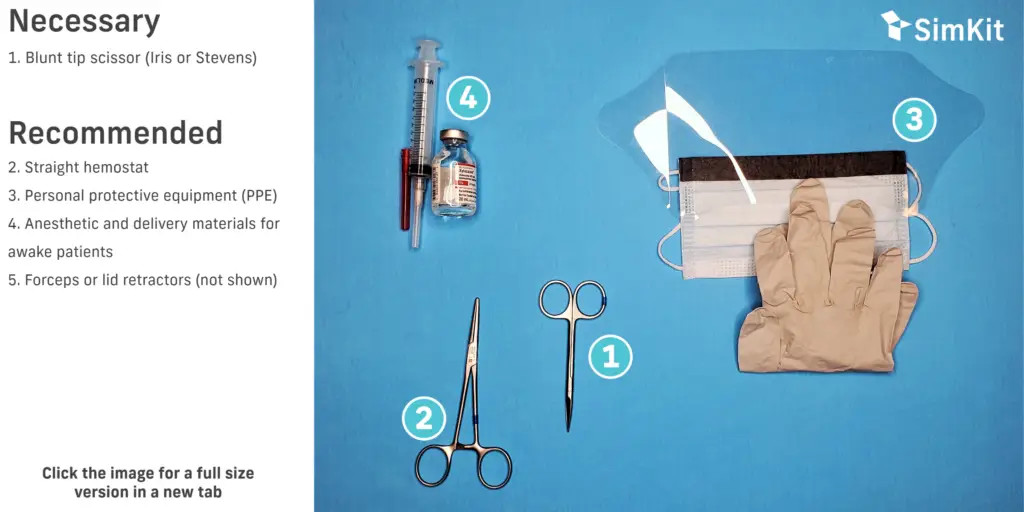

C. Materials

D. Steps

Step 1 | Anesthetize

Cleansing beforehand is recommended. Povidone-iodine (Betadine) is the ideal antiseptic around the eye, but must be diluted to 5% (typically a 10% solution). This can be done with 1 to 1 dilution with sterile saline or water.

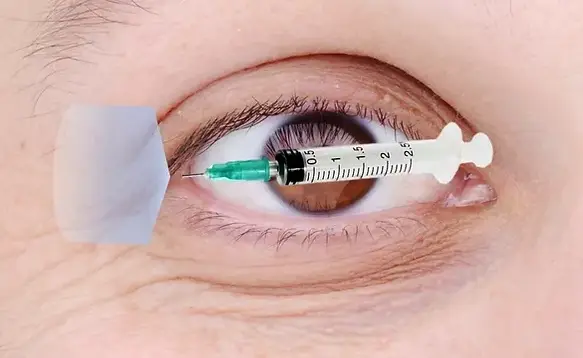

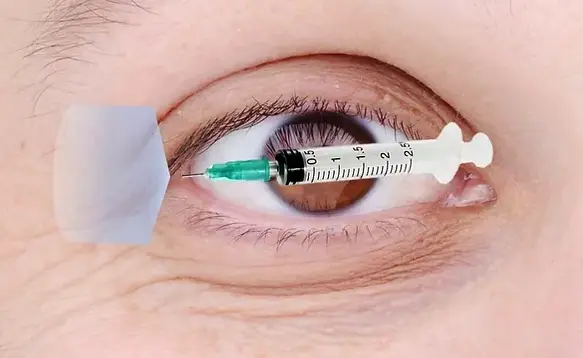

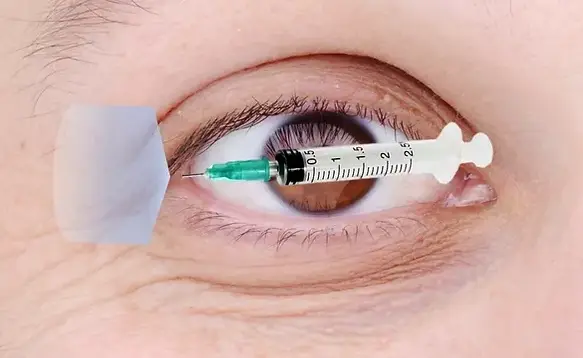

If the patient is awake, anesthetize with local anesthetic (lidocaine, ideally with epinephrine). The needle will be inserted superficially and from a medial to lateral plane, into the lateral canthus and toward the orbital rim. Aspirate to verify no blood return then inject as you slowly withdraw the needle. See associated picture of needle orientation and area to anesthetize.

Step 2 | Crush the canthus

With one side anterior and one side posterior to the lateral canthus, advance your hemostat ~1 cm until the orbital rim is felt. Clamp for 1-2 minutes. This helps minimize bleeding.

Step 3 | Cut the canthus

Using your blunt tipped scissors, cut though the crushed line.

Note: the point of this step is to make the release and visualization of the tendons easier. During this and subsequent steps a lid retractor (bent paperclip will suffice) may be necessary.

Step 4 | Cut the inferior crus

Sweep your open scissors up along the palpebral conjunctiva of the lower lid toward your lateral canthotomy incision. When you feel resistance, you have found the inferior crus of the lateral canthal ligament (like a tight rubber band). You may also be able to visualize the tendon itself. Once identified, incise the ligament.

Note: This may be enough to relieve the pressure. An optional step here would be to check pressure and, if below 40 mm Hg, the procedure is complete. Often the superior crus needs incision as well and some recommend continuing on to this step to avoid excessive delay.

Step 5 | Cut the superior crus

In the same manner as the inferior crus, sweep along the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper lid from medial to lateral until resistance is felt. This represents the superior crus, which again may be visible. Incise the superior crus of the lateral canthal ligament.

Step 6 | Recheck pressure

After release of the canthal ligaments, recheck IOP.

References

[1] Knoop K, Dennis W, Hedges F. (2017). ‘Ophthalmologic Procedures” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Publisher. Pp. 1141-1177.

[2] Shannon B. “Acute Orbital Compartment Syndrome.” https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/799528-overview#showall March 2020.

[3] Oester A, Fowler B, Fleming J. Inferior Orbital Septum Release Compared to Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis in the Management of Orbital Compartment Syndrome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Jan; 28(1): 40–43.

[4] Gardiner M. “Overview of eye injuries in the emergency department.” https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-eye-injuries-in-the-emergency-department March 2020.

Lateral Canthotomy Procedure

Welcome to the Lateral Canthotomy procedure page. Here we will cover indications, contraindications, materials and steps for you to master this procedure. Let’s begin below with the procedure video!

Procedure Video

A. Indications

The indication for this procedure are signs and symptoms of acute orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). The most common cause of acute orbital compartment syndrome is trauma leading to retrobulbar hematoma.[1] Other traumatic causes include intraocular hematoma, subperiosteal hematoma, and sinus fractures with orbital emphysema. Outside of trauma, the most common causes of OCS are facial surgery and orbital cellulitis.[2][3]

It is important to recognize acute OCS is a clinical diagnosis. The symptoms include ocular pain, limited eye movement, and visual impairment. The associated signs are proptosis, decreased visual acuity in the affected eye, limited extraocular movement, afferent pupillary defect, and increased intraocular pressure (IOP). If measured, a soft cut point for IOP is >40 mmHg as an indication for decompression.

Acute OCS is a time sensitive emergency, and therefore imaging should not delay treatment, unless more significant life threats (intracranial hemorrhage etc.) require rule out first, which is often the case in these traumatic cases. In these instances, the retrobulbar hematoma is often then seen. Other findings that suggest OCS include proptosis, afferent pupil defect and, in the alert patient, decreased visual acuity.[4] While >40 mmHg IOP is the textbook answer for this procedure, patient presentation and characteristics must be considered. In the right patient (for example: retrobulbar hematoma, proptosis, significantly reduced visual acuity), lateral canthotomy may be indicated despite IOPs below 40 mmHg.

Note: The procedure is technically a combination of a lateral canthotomy and inferior (+/- superior) cantholysis.

B. Contraindications

Globe rupture is the only absolute contraindication to lateral canthotomy. This can be diagnosed clinically or by advanced imaging (CT). Alternative causes for high intraocular pressure (acute angle closure glaucoma) should be ruled out before lateral canthotomy is performed.

C. Materials

D. Steps

Step 1 | Anesthetize

Cleansing beforehand is recommended. Povidone-iodine (Betadine) is the ideal antiseptic around the eye, but must be diluted to 5% (typically a 10% solution). This can be done with 1 to 1 dilution with sterile saline or water.

If the patient is awake, anesthetize with local anesthetic (lidocaine, ideally with epinephrine). The needle will be inserted superficially and from a medial to lateral plane, into the lateral canthus and toward the orbital rim. Aspirate to verify no blood return then inject as you slowly withdraw the needle. See associated picture of needle orientation and area to anesthetize.

Step 2 | Crush the canthus

With one side anterior and one side posterior to the lateral canthus, advance your hemostat ~1 cm until the orbital rim is felt. Clamp for 1-2 minutes. This helps minimize bleeding.

Step 3 | Cut the canthus

Using your blunt tipped scissors, cut though the crushed line.

Note: the point of this step is to make the release and visualization of the tendons easier. During this and subsequent steps a lid retractor (bent paperclip will suffice) may be necessary.

Step 4 | Cut the inferior crus

Sweep your open scissors up along the palpebral conjunctiva of the lower lid toward your lateral canthotomy incision. When you feel resistance, you have found the inferior crus of the lateral canthal ligament (like a tight rubber band). You may also be able to visualize the tendon itself. Once identified, incise the ligament.

Note: This may be enough to relieve the pressure. An optional step here would be to check pressure and, if below 40 mm Hg, the procedure is complete. Often the superior crus needs incision as well and some recommend continuing on to this step to avoid excessive delay.

Step 5 | Cut the superior crus

In the same manner as the inferior crus, sweep along the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper lid from medial to lateral until resistance is felt. This represents the superior crus, which again may be visible. Incise the superior crus of the lateral canthal ligament.

Step 6 | Recheck pressure

After release of the canthal ligaments, recheck IOP.

References

[1] Knoop K, Dennis W, Hedges F. (2017). ‘Ophthalmologic Procedures” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Publisher. Pp. 1141-1177.

[2] Shannon B. “Acute Orbital Compartment Syndrome.” https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/799528-overview#showall March 2020.

[3] Oester A, Fowler B, Fleming J. Inferior Orbital Septum Release Compared to Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis in the Management of Orbital Compartment Syndrome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Jan; 28(1): 40–43.

[4] Gardiner M. “Overview of eye injuries in the emergency department.” https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-eye-injuries-in-the-emergency-department March 2020.

Lateral Canthotomy Procedure

Welcome to the Lateral Canthotomy procedure page. Here we will cover indications, contraindications, materials and steps for you to master this procedure. Let’s begin below with the procedure video!

Procedure Video

A. Indications

The indication for this procedure are signs and symptoms of acute orbital compartment syndrome (OCS). The most common cause of acute orbital compartment syndrome is trauma leading to retrobulbar hematoma.[1] Other traumatic causes include intraocular hematoma, subperiosteal hematoma, and sinus fractures with orbital emphysema. Outside of trauma, the most common causes of OCS are facial surgery and orbital cellulitis.[2][3]

It is important to recognize acute OCS is a clinical diagnosis. The symptoms include ocular pain, limited eye movement, and visual impairment. The associated signs are proptosis, decreased visual acuity in the affected eye, limited extraocular movement, afferent pupillary defect, and increased intraocular pressure (IOP). If measured, a soft cut point for IOP is >40 mmHg as an indication for decompression.

Acute OCS is a time sensitive emergency, and therefore imaging should not delay treatment, unless more significant life threats (intracranial hemorrhage etc.) require rule out first, which is often the case in these traumatic cases. In these instances, the retrobulbar hematoma is often then seen. Other findings that suggest OCS include proptosis, afferent pupil defect and, in the alert patient, decreased visual acuity.[4] While >40 mmHg IOP is the textbook answer for this procedure, patient presentation and characteristics must be considered. In the right patient (for example: retrobulbar hematoma, proptosis, significantly reduced visual acuity), lateral canthotomy may be indicated despite IOPs below 40 mmHg.

Note: The procedure is technically a combination of a lateral canthotomy and inferior (+/- superior) cantholysis.

B. Contraindications

Globe rupture is the only absolute contraindication to lateral canthotomy. This can be diagnosed clinically or by advanced imaging (CT). Alternative causes for high intraocular pressure (acute angle closure glaucoma) should be ruled out before lateral canthotomy is performed.

C. Materials

D. Steps

Step 1 | Anesthetize

Cleansing beforehand is recommended. Povidone-iodine (Betadine) is the ideal antiseptic around the eye, but must be diluted to 5% (typically a 10% solution). This can be done with 1 to 1 dilution with sterile saline or water.

If the patient is awake, anesthetize with local anesthetic (lidocaine, ideally with epinephrine). The needle will be inserted superficially and from a medial to lateral plane, into the lateral canthus and toward the orbital rim. Aspirate to verify no blood return then inject as you slowly withdraw the needle. See associated picture of needle orientation and area to anesthetize.

Step 2 | Crush the canthus

With one side anterior and one side posterior to the lateral canthus, advance your hemostat ~1 cm until the orbital rim is felt. Clamp for 1-2 minutes. This helps minimize bleeding.

Step 3 | Cut the canthus

Using your blunt tipped scissors, cut though the crushed line.

Note: the point of this step is to make the release and visualization of the tendons easier. During this and subsequent steps a lid retractor (bent paperclip will suffice) may be necessary.

Step 4 | Cut the inferior crus

Sweep your open scissors up along the palpebral conjunctiva of the lower lid toward your lateral canthotomy incision. When you feel resistance, you have found the inferior crus of the lateral canthal ligament (like a tight rubber band). You may also be able to visualize the tendon itself. Once identified, incise the ligament.

Note: This may be enough to relieve the pressure. An optional step here would be to check pressure and, if below 40 mm Hg, the procedure is complete. Often the superior crus needs incision as well and some recommend continuing on to this step to avoid excessive delay.

Step 5 | Cut the superior crus

In the same manner as the inferior crus, sweep along the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper lid from medial to lateral until resistance is felt. This represents the superior crus, which again may be visible. Incise the superior crus of the lateral canthal ligament.

Step 6 | Recheck pressure

After release of the canthal ligaments, recheck IOP.

References

[1] Knoop K, Dennis W, Hedges F. (2017). ‘Ophthalmologic Procedures” in Roberts J. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. Publisher. Pp. 1141-1177.

[2] Shannon B. “Acute Orbital Compartment Syndrome.” https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/799528-overview#showall March 2020.

[3] Oester A, Fowler B, Fleming J. Inferior Orbital Septum Release Compared to Lateral Canthotomy and Cantholysis in the Management of Orbital Compartment Syndrome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Jan; 28(1): 40–43.

[4] Gardiner M. “Overview of eye injuries in the emergency department.” https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-eye-injuries-in-the-emergency-department March 2020.