The balance of work and life can sometimes feel artificial. Isn’t work part of my life? Is there such thing as work-life balance? Most importantly- How can I think about and structure my life to be my happiest, most productive self?

In this podcast we sit down with Dr. Rob Orman, creator/host of the Stimulus Podcast, physician life-coach, and world-renowned EM educator to talk about life, Emergency Medicine work, the interplay between the two, and ways to strike a healthy balance.

Jason Hine: Hello everybody and welcome back to the SimKit podcast. I am joined by an ultra, ultra special guest today. The gentleman who really probably needs little or no introduction outside of his own name. I am joined by the great Rob Orman. Rob, thanks for talking with us today.

Rob Orman: Alright, I’ll say first. I guess I’ll say you’re welcome, but obviously thank you for that ultra, ultra, I got an ultra squared intro, that was a… man and I know some of the people who have been on your podcast, so that’s what a tremendous compliment.

Jason Hine: It’s a high bar. I want you to be nervous that you’re going to underperform.

Rob Orman: This is, after all, the SimKit podcast. Wait a second, this is ohh this is, this is how it works when you go into SimKit like in the debrief is when it’s all nurturing and okay.

Jason Hine: Yes, this is the stress. But, Rob, you, Sir, you, I mean, you’re a busy guy. You’ve been behind some of the most influential medical education podcasts for emergency medicine. You are the voice of the amazing stimulus podcast and you’re a life coach for clinicians. You seem to be an individual who has this whole “work-life balance”, figured out. So my first question for you actually comes in the form of a quote, “There’s no such thing as work-life balance. It is all life. The balance has to be within you.” Namaste, now I added the Namaste, but what are your thoughts about that?

Rob Orman: Where’s that quote come from? I love that.

Jason Hine: Ah, so I actually use headspace. I don’t have any stock in them, but I do use them as in one of my meditation apps that remind me to do it. And it came from them. That’s where I sort of found that and it tickled my fancy. And I’m curious what you think about it.

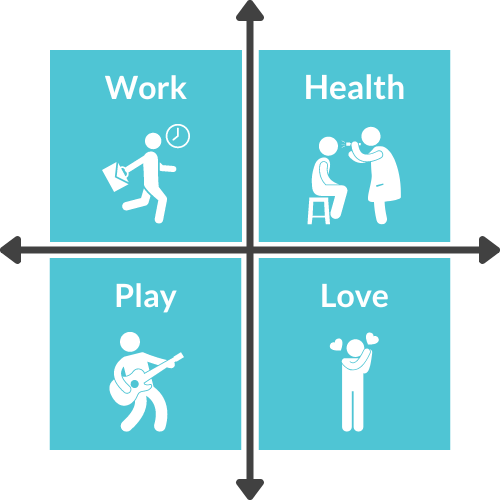

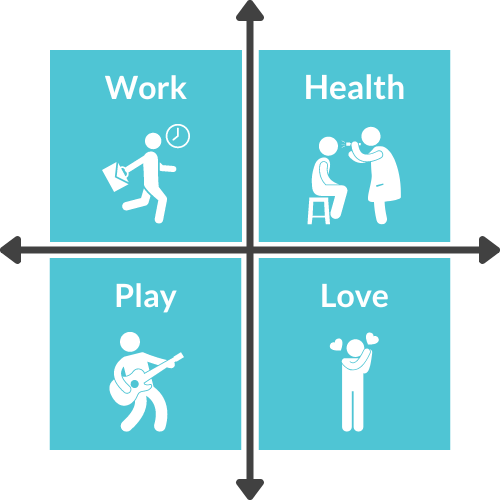

Rob Orman: Ah, so true. I love that it just, I mean it just rings in the affirmative in my brain when you said that and I think there’s a lot of ways to break down the different things that you do in life you know like put them in silos delineate this from that but, really, I mean, you’ve just got so much time in your life. What are you going to do with it? And you know, I think that. Yeah, there is a thing. And I fully embrace the kind of ethos of that quote. But I think it can be helpful to deconstruct your life in different quadrants or categories where you look at, where you might be unbalanced, so looking at the whole thing in composite. Yeah, here’s all the things that are in my life but we think all right, where am I maybe putting too much attention or too little attention? What’s oversubscribed or undersubscribed, so for example, with new clients. I have them do as part of a self survey, a dashboard indicating where they are over attending or under attending. And you know you can do this in any way, but this happens to be work, health, play, and love. What is happening in work, health, play, and love? And when you look at all of those things, when you look at them globally. What’s, what’s, not getting enough attention? What’s getting too much attention? And for physicians, it’s often well, work is getting a lot. Or it’s actually it’s, it’s interesting work is usually just all the way to the red line. Or sometimes if there’s too much and someone is just really burnt out, it can be at 0. This is kind of like this feeling of collapse. And there’s nothing magical or precious about those things. I actually got them from a book called Designing Your Life. And I thought it really made sense dividing things up this way, but really all of those things are just life. And one of the things, one of the traps that you can fall into with work is that work becomes the ultimate protected thing in your life, right? I mean, we know that, hey, I’ve got this, I’ve got this shift and it’s going to take well, even some kind of natural disaster, especially in going to the shift. Nothing is going to happen. Get in the way. You and I. You and I both know we have friends, let’s just say, who have worked with an IV in their arm getting rehydrated when they’ve got gastroenteritis or whatever it’s like. And so the boundary around that is amazing, right? It’s great, but the other things in life don’t necessarily get that protection. That can be a problem. You know, it’s when you, when you look at what is really important in life or I mean the well this has been studied there’s the grant study which is the longest running research on happiness looked at what makes a good life and they study people throughout the course of their lives and now it’s multi-generational. And what they found, the consistent factor is relationships. Quality relationships more than social class, more than income, more than IQ, more than any of that stuff. And so, we just get in the habit of putting a boundary around this one thing, whereas hey, there’s all this other stuff in life where we need to be attentive to, you know, to, to really have a fulfilling experience with life. You know, I’m sort of going on a polemic here, so I’m going to pause and I want to hear your thoughts on that.

Jason Hine: No, I like that sort of breakdown and I think it you, you end up with the sort of question of like do you dichotomize life into work and life that’s kind of what the quote was about, right? And you from your sort of example: work, health, play, love. Well, then it’s it that breaks it down further. There’s work and you’re taking life and you’re breaking it down a little bit more into health, play, and love, and eventually, you just break it down into so many segments that it’s indistinguishable. But there are areas of our lives that seem like they need focus. And work just draws our attention. Like you said, you die to make sure that you get to your shift and do the work that you do as an emergency physician. But are we putting the same energy into health, play, and love?

Rob Orman: I love that word dichotomizing. I just wanna… just wanna acknowledge I, you know, I I don’t think this is the elephant in the room because we’re talking about it. But, let’s just say an elephant in the room is that most of us are oversubscribed to work in some way or another. If we’re going to dichotomize, which is fine, you know, I think, it’s great to say, It’s all life, okay, here is my life. But, what are the areas that I need to attend to? We are most of us are oversubscribed to work in one way or another. Either in the time we put into it, or the stress that is attached to it.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: It doesn’t necessarily have to be like, oh my gosh, you know, a lot of, a lot of clinicians right now are working more shifts than they want. Yeah, that’s just … And we don’t need to go into how that happened, but it doesn’t even have to be the case. It’s just, even those shifts with boarding, with under-resource, with collegiality decay, with increased friction, it’s just so hard to get things done. There’s so much stress attached to it. I would imagine this is the case for you. I come across very few clinicians who are bored, not working enough.

Jason Hine: With their work. Yeah, right, exactly.

Rob Orman: Yeah, Ah, I’m trying to think. No, I can’t think of anyone in the past couple of years who has said, I need to put more energy and focus into work. Now learning, yes. But, work, no. Like personal development and professional development and you know we were talking before this, you know, thinking what you’re doing, which is basically postgraduate graduate, postgraduate education for people who are out of training. And then these Halo procedures, this high acuity, low opportunity procedures, you sort of lose your sharpness with it. Okay, there’s something where people need to put more… Wait a second, I think I just did an ad within the show. But that’s where people really feel compelled to put more energy into, but not the work itself.

Jason Hine: Right, right, the performance of the work as opposed…

Rob Orman: Yes, right, so when you’re talking about dichotomizing life, I think I think it can be helpful to construct when it becomes maladaptive, so when we see anything that is dichotomized as truly being separate from the whole. Like I am, I exist on a different plane when I am working. No, you’re still the same person.

Jason Hine: No, yeah, you’re, you’re still Rob or Jay. Yeah, I agree. As an aside on that, I’m curious your perspective, you know, we’re talking about that non dichotomizing or putting your work on a completely separate plane. And I want to come back a little bit to, you know, we’re saying that with work, it may not be the number of hours that is being taken from you at a higher percentage than you. You’re at home more than you are at work, but the amount of energy or life force that’s going into that, there’s so much of a draw, or probably the opposite, a suck of your person, because our shifts are so demanding of us. So one area that I’ve sort of tried to focus on is sort of leaving work at work to not bring my work experience into the home life, and certainly not difficult cases, or patients, traumas, you know, food insecurity, all of that stuff. So, what is your thought process on that, you know we don’t want to dichotomize, we don’t want to exist on a different plane, but, we can’t bring emergency department life into our home? It’s not good for our spouses or our children.

Rob Orman: That’s so common to have that experience of, how do you transition really? Well, how do you transition? Let’s talk about the end transition, so transitioning from a shift to home because there’s also transitioning into the shift, but I think, and you know you’re, especially a night shift, your day before you’re thinking about the night shift.

Jason Hine: Yeah, for a while.

Rob Orman: Yeah, but that, but that afterward, there are so many different aspects to this, but, first, let’s talk about transitioning to home. So basically, from your work brain to your home brain. And you know your work brain is so focused on all of that stuff that you’re talking about and it’s really it’s, it’s going so fast in one way and in another way, it’s also depleted. You know you’re depleted of your serotonin and your dopamine. And just like, just tired and it’s like you need to do this reset before you’re able to engage with your family, I mean and it just, it just takes time and it does take intention. And so, what I started doing and I, you know, work with clients on as well is: how do you intentionally transition from work brain to home brain? How do you do it? And there’s a couple ways. There’s sort of a, there’s like a long term aspect of this, and then there’s the short immediate aspect. And one exercise and there’s myriad ways to go about this. But one exercise I have docs do is, right before they get home, is basically, process the day. Because that, that’s what needs to happen, if we don’t process it. It just happens and boom, we’re into home.

Jason Hine: Okay, yeah, out the door, in the car.

Rob Orman: So, if you have a commute, if you have a commute home. You go from work, to home and it could be on a bike, it could be in your car, and before you go in the door, and if you have young kids, I recommend you park like a block or two away from home so people can’t see you. Yeah, because you know some people get in the garage and…

Jason Hine: Yeah, the driveway, six kids from running out. Yeah. Dogs are going to scratch the door like, yeah, yeah.

Rob Orman: Exactly Yeah, it just kind of you know, it just takes some time and space in that commute to, you know, listen to music or if you listen to podcasts or nothing. And then before you get home. Take 5 minutes and just sit in that car. Take some breaths, take some deep breaths and see if you can turn down the amplitude of that, of what is really a sympathetically activated or charged state, you know? You’re up, upregulated? Just some deep, slow breaths with longer exhales than inhales. Deep in through your nose, out through pursed lips, in through your nose, out through pursed lips. There’s a lot of different ways to do the breathing exercises, to down-regulate. Just start turning things down. And then when you feel that things are a little bit calmer, a little bit less static in the brain, then walk through the day, just walk through that whole day. And think about, what did I see? What did I feel? It’s almost like a personal debrief, and what went well? What were some great moments that day? And you look at the patient and sometimes it’s just a thank you or uh, you know, credible procedure or…

Jason Hine: Joke from a spouse or something, something even silly.

Rob Orman: Yeah, exactly! So you’re processing that and you’re just kind of going through it and and then? What’s one thing I could have done better, right? What’s my learning point? How am I going to grow from this? And it could be, I really didn’t know as much about the PECARN fever rule for 21 to 28 days, and so okay, I’m going to, I’m going to read up on that or I’m going to take some action.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: And, what you’re doing here, is you’re taking action. You are processing, it’s a little bit of reflective processing afterwards. I mean you could journal this or you could think this. I find it’s easier just to sit in your car and think this through so that you can process it. And then, I have a friend of mine who I do a lot of work with is a psychotherapist. We’ve kind of developed this process together. What he does is he, he imagines that all of that stuff, kind of gets condensed into a balloon, and then he visualizes himself, snip, cutting the cord, snip, cutting the cord, and letting it float away.

Jason Hine: Oh, letting it fly away.

Rob Orman: And then boom, goes into the house.

Jason Hine: Nice!

Rob Orman: And, yeah! So, there’s a lot of different ways to do that. And so that’s, that’s just one example of an acute transition from work to home, and there’s other ones that you know, you get home and then you’re thinking about these cases, right? There’s one client who called this afterburn, the afterburn, you know, residue would be the more common, the common cause. And, I just want to tell you this incredible thing, that really she worked out. I guess we worked out together. I have to give her the credit for this. It’s quite incredible. So. there were things that would just stick with her, you know, just kind of cases that you ruminate on, let’s call it rumination. And that impacts the quality of your experience with your family and the rest of your life and your relationships. So, I went back and identified what those situations are right? Go in your shift and identify those situations where what is it that you’re thinking about and you made a list. So it’s made a list, and it’s usually a situation where you don’t have enough information and you have to make a decision and then you go home and you ruminate about it, right, you know, like an equivocal chest pain, or, you know, this patient had this kind of weird symptom. I’m not quite sure. So, out of this came the letter to my future self.

Jason Hine: Okay.

Rob Orman: So, we identified these pivotal moments. Where later on, she would ruminate, or one would ruminate. And so, I took a pause in those moments, and mentally would think to herself, dear future self, at this moment I am making the best decision possible based on the information I have. And you know, the first time it’s kind of like kind of clunky, but after 100 times doing that, that builds that mental muscle.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: Uh so, just two examples of how to not necessarily separate, but really, I would say how to integrate that work experience into, into you. And I say integrate like you would integrate sugar into water. You know, you pour it in there and it dissolves.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: It makes it a little sweeter. In the end, that’s integrated. Versus disintegration, which should be like pouring oil on water and it never fully gets processed or becomes part of.

Jason Hine: Yeah, I like that, I think um, there’s two parts to that. I mean, the letter to my future self I think is a great way to sort of avoid your self-criticism. Your Monday morning quarterbacking of yourself, you go back in a chart, the next day someone finds the answer to the diagnosis, and you’re like oh man, I’m not good at this. I didn’t ask the right questions. But, you’re making the right decision. Or the, not right, the best possible decision you can with the information you have. That’s a fantastic way to keep yourself from beating oneself up because our job is hard and we don’t always have the information we need to make the best decision. But we make the best, for the time with the space and information that’s great. I love the letters to my future self and I really like the idea of cutting off the balloon. This sort of active, almost de-escalation, you know this, this active turning of oneself off, because I have always found that particularly, you know, we have a shift that ends at 2:00 in the morning. And I’ve got, I have kids. I get home at 2:30 and I find it’s four in the morning after watching a show that I’m like, okay, I should probably go to bed now. And I feel like my brain is ready to do it. And like, what a dummy! Why did it take me an hour and a half to get myself to a state where I can do that? I think it’s because I’ve used commonalities of, you know, shows and simple distracting techniques to slowly and passively de-escalate myself. But I think if you actively do that, man, you’re gonna find that you don’t have to do this dragging-on process that brings you to 4:00 in the morning after 2:00 AM shift, that’s, that’s super helpful for me.

Rob Orman: I love that you brought up the TV thing. So, for over a decade. Well, I don’t know, I can’t remember when Netflix… Actually, I actually started this back in a time when I was recording shows on VHS tapes. So, this goes way back, I’d come home.

Jason Hine: A long time ago.

Rob Orman: Yeah, baby, a long time ago. This goes back many years. And just like you, I would watch regularly, especially on those late shifts, when there was no accountability for what I was doing.

Jason Hine: Right.

Rob Orman: Four hours of TV from 2:00 AM to 6:00. I mean 6:00 AM, and I gave myself a freaking night shift. And it was just, it’s the equivalent of, oh, I’m gonna drink a couple glasses of Scotch. Well, we know that, oh, you don’t drink alcohol before you go to sleep? Well, we probably shouldn’t watch 4 hours of TV before we go to sleep because we just want to. You know that the brain is just so freaking on. I mean, emergency medicine is so hard. It’s so cognitively demanding. I can remember, I didn’t appreciate this so much until I was like a third-year resident. I just kind of took it for granted, that ohh beep bop, beep bop, beep bop. You know, kind of going around. I had, not even a like, a severe headache, I had an ocular migraine during a shift, I get migrants all the time, whatever I mean that really bugged me too much. But, I could only see out of one eye.

Jason Hine: That’s a problem.

Rob Orman: That was it, I could, I could think fine it was just, you know, it’s just this one thing that just skewed me a little bit. And the whole thing just fell apart. It was like the amount I, and I was like, whoa, I can’t believe it. We talked about this, how much you’re processing. You know, you’ve got like 1000 data points per hour and all that stuff, it really is. It really is so much, and you know, you start off that first patient in the shift and you’ve got, you know, you got one ball, you’re throwing up, throwing up. And by the end of it, it’s 100 balls. You’re juggling it. And that volume is turned up really high. I mean it’s, I guess it’s not, you watch the Benny Hill Show? This might be…

Jason Hine: Uh, I know of it. I did not watch it. It’s on VHS, I’m assuming.

Rob Orman: I know. Oh my God, I’m dating myself. They used to have these montages where they would speed things up like 2X or 3X time and have them running around, that’s what, you’re like!

Jason Hine: Yeah!

Rob Orman: And your brain can’t just say, boom, click and so that’s why you know, we would watch all those hours of TV just for the time.

Jason Hine: Yeah, to stop the tornado. Yeah, slow down.

Rob Orman: Yeah, I like that. Just how do you slow down a tornado? You let the tornado go, or in this case, you can come up with a routine or with a habit that’s probably in the long run, healthier for you. Because, I mean, you and I both know, after years and years and years of that, those decreased sleep windows, especially you know when you’ve got kids, you’ve got a family, those decreased sleep windows add up to physical and physiologic stress.

Jason Hine: Yeah. Yeah. And I mean, if people aren’t aren’t drinking the kool-aid on this, I think this is great. I think it’s the way to do it as opposed to like you said, two to four hours of TV after a shift. But, even if you’re just that type A or you’re that motivated to be the highest performing person you are, it’s more efficient, right? If you need no other reason you know then I need, I can’t spend that length of time to de-escalate and slow my brain down. You spend the 5 minutes actively doing it versus the two to four hours of TV passively, then you’re being efficient. But yeah, I did want to bring it back a little bit, so we’re sort of talking about ways of at least deescalating oneself or bringing oneself from the work to the home environment and even the little vice versa. But, coming back to these, you know these silos, if you have them or these dichotomous areas or if you have the four elements that you mentioned. I just kind of wanna give you an analogy for life that I’ve used and see how that plays into what we’ve talked about with the important parts of one’s life.

Rob Orman: Okay.

Jason Hine: So I’ve used this for a long time. It’s the life-as-a-barrel analogy. You have a barrel. your life is actually the barrel and it’s yours to fill. And you can fill it, fill it with whatever you want. Whatever you so choose. You start with though, with your big really high priority items. These are the things that have to go on first because they’re so important and so large that you need to make sure they fit. In my mind, these are the boulders. It could be your spouse, your family, your physical or mental health, could be a passion that you can’t live without. Say you’re an avid painter or sailor or you’re, you know, big into philanthropy. Whatever it is for you, you know, career, certainly for many would be one of those boulders. They are large and they have to be put in first to make sure that they fit. Once you filled your barrel with your boulders, it’s packed to the top, then you think, okay? Is it filled? Is my barrel full? Is my barrel of light full? But of course, it’s not right. Then, you have rocks that you get to fit in between these boulders. And once you pack the rocks, you can choose to add sand, add the sand, filling in the gaps. Now some people kind of just want that to be empty space. No sand, just empty space to enjoy themselves. But, many people like myself, just want life to be as full and active as comfortably possible. That’s how I feel well and function best. So we pour in the sand. And then once the barrel is brimming with boulders and rocks and sand, you imagine you can’t possibly put anything else into the barrel. Well, then you crack 2 beers and you pour them in there, just as a reminder. There’s always room for a couple of beers. What are your thoughts?

Rob Orman: Okay. Oh my God, there’s so many. I’ve never heard the cracking beers. In addition to the rocks and pebbles and sand metaphor, I mean, yeah, you, I’m gonna say you’ve hit the nail on the head with the beer cracking. Uh, you know, I have a I just, I just wanna talk personally because this is this, I don’t think you could get more personal than this because this is how you spend your life, what you do with your time. I try to leave as much space between the boulders and rocks as possible and not pour in sand. Just to have empty space.

Jason Hine: That’s fair.

Rob Orman: And, whether it’s reflective space or just not so much tightness in the schedule that there’s not room to breathe. And, I just, over time, have come to value that more, the non sand space.

Jason Hine: I agree with you, I think, and maybe that comes from parenthood, because you need spontaneity, right? You need to have room for spontaneity.

Rob Orman: Yeah, yeah.

Jason Hine: Because you need spontaneity and if your sand is packed around other rocks and boulders and you may not have space for that, but yeah. I think for me the the analogy really essentially deteriorates or it really only has value through the boulders, right? You’re not labeling what your rocks are. You’re not labeling. Okay, this academic project is my sand. But once you identify your boulders, that’s the most important, nothing else can interrupt that. Right? Do you personally, do you have a variation or a different way of visualizing the same sort of thing?

Rob Orman: Yeah, I would say I do and more intentionally over recent years. I didn’t used to.

Jason Hine: Okay.

Rob Orman: Would be, I just would take on whatever shiny object came my way.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: And, um you know, I was, I will say, that you know, as I’m thinking about boulders and sand. I fall prey to prioritizing sand on a regular basis.

Jason Hine: I’m with you there. Yeah.

Rob Orman: And this, it’s like, oh, yes, the boulders always take priority, although you have three or four boulders at a time. No man, I mean I think sand is so attractive and I do. I do periodically take stock of what I’m doing personally and professionally and how many big ticket items, big rocks I’m working on. And if there’s too many, what can be put on the shelf for a while or put in a holding pattern? You know, I love that you hit on a key aspect of what these rocks or boulders can be. And most of us think that rocks or boulders are, you know, creative projects, are work, but family and health are also part of this. And for example, so I work with a doc on overwhelm. One of the things we do is we list out everything that’s on their plate, big, small or whatever, and in the framework we’re discussing, we’re going to list out the boulders, the pebbles, the sand, and you see pretty quickly that it’s just a mishmash with no prioritization. So, we break it down and we find out, what are the boulders and how many of these are at play? What are non negotiable? What can be put to rest for a while and attended to later? And what simply, and this is, so hard yet so freeing, what just need to be jettisoned? You know, so.

Jason Hine: Sure. Yeah.

Rob Orman: What is this thing giving you? What is this thing costing you? And it’s funny you know when you work with high-level performers, which, physicians, and especially emergency physicians are, sometimes there will be this burgeoning ambition to create something incredible and you know, it’s like where I would have put my energy. And most of the time, it ends up being some creative project, some reformation or some, you know, I don’t know, like, what’s the opposite of a tributary, some offshoot of their work sometimes. And this is really interesting as as we go through this it’s like, ohh yeah, you know, creative project, creative project, and I’d say about half the time, the boulder or project of that burgeoning ambition ends up being a relationship of oh yeah, actually it turns out that this is where I really need to be attentive and have this be, a key, like the big boulder in the middle of my barrel.

Jason Hine: Yeah, well, I have no idea what you’re talking about, by the way as a guy who’s trying to create this project that you’re joining to talk, talk with me on. But, um that makes a ton of sense, and I think that mishmash that you described for one of your physicians is very true for most of us. I have this in my mind and I have the idea of what my boulders are, but on a day-to-day basis, it can wax and wane and you can falsely label work or a project that means little to you. You know, I love that idea. What do you give to it versus what does it take from you? You know, very imbalanced projects like that that you’re labeling inappropriately as boulders. But I think one of the greatest challenges in that realm for me is how active versus passive, these elements to keep with the analogy, pull our attention, right? So the sand seems to be so active and the boulders in a lot of ways are passive. And to explain that further kind of as an example, you know we’ve talked a bit about that I’m a father and so for many with a family, parenthood is a major boulder. For me, it may well be my purpose in life, but, and I make no claim to being particularly great at it. I’m learning as I go, but you know the reality is my children, barring any kind of tragedy that we’re not gonna dive into today, they’re always going to be there. I can be an active, engaged father with them at almost any point in time. But the book chapter that has those deadlines, the hospital committee that meets biweekly, those things actively draw your attention. So, Rob, have you come to find this imbalance between sort of importance and urgency in life work and if so, how do you, how do you handle it? Or how do you recommend people do so?

Rob Orman: Whoa…

Jason Hine: That’s a deep question.

Rob Orman: You know, I think that there’s a couple aspects to this. On a global perspective, there are times when, let’s go back to the gauges for a minute: work, love, health and play. Yeah, and say like, okay, I’d like for these to be balanced. It’s not, you know, not everything’s gonna be right down the middle all the time. Sometimes some of those things are gonna need to be really turned up, you know, like. You’re starting this business. You’re doing this thing. It’s like, okay, you’re really putting a lot of time and energy into it.

Jason Hine: Yes.

Rob Orman: That, that start-up time or that like sweat equity you’re putting won’t always be. So, you just know, okay well for this period of time I’m going to be you know, working on this, and then I know I’m going to turn that down. So, I’d say that they’re always in flux and that just something when you’re going through that thinking, yeah, it’s a, there’s always going to be a, a, a calibration and a recalibration, and it’s not necessarily like what works too much right now, gotta turn it down for sure. It’s just all right. How’s this fitting in the rest of my life? What’s this gonna look like for the long term? But from a personal standpoint, which I think what you asked, I work at home and I retired from clinical medicine. Boy, it’s coming up on four years ago. And so because I work at home, it means I live at work.

Jason Hine: That’s true, I never thought that other side of that.

Rob Orman: Yeah, so. So, which means that it’s easy to be on 24 hours a day and it’s easy to get sucked into work and give it massive importance. Yeah, and you know, you, you and I both do a lot of creative work. And what is the death of creative work? Interruption. That’s it, it’s interruption. That’s what you know, when we talk about deep work, what’s the whole thing about deep work? It’s uninterrupted time. I used to rankle, let’s say, let’s use the word rankle at interruption when I was doing creative work.

Jason Hine: Okay.

Rob Orman: And then I, just kind of looking at this global thing as we’re doing, I think, alright, what’s actually, what is my life, what’s important? So I made a hard and fast rule that unless I was involved in something I truly could not get out of, whenever my kids would ask for my attention, that was immediately priority one. Now, this happened when my kids were teenagers. And you know, right over to my right, it’s the office I work in, has glass doors. So, like anyone can come here and get my attention. And that has gone on to apply to big and small things. You know, the daily machinations of life and then planning what happens, the big picture of life. For example, I don’t travel a lot for speaking. It’s not that there’s not opportunity. It’s just that that’s not where I want to be spending my time. I, you know, I want to be home with my family, that’s a trade-off. But so, but for example, over the next couple of months I will be, I think I’ll be traveling like four times in two months to, you know, to conferences to talk. Because there’s something I want to talk about. There’s something I feel needs to be spoken to people live.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: And not on a zoom talk. It’s just me, that interaction needs to happen with groups in person. So I, so that’s important and there’s trade-off again like that’s not something that I will regularly do, but I know I’m going to just turn that dial up for a short period of time, and then I’ll turn it back down.

Jason Hine: That, what is it giving to you versus what is it taking from you, that’s pretty balanced in that circumstance.

Rob Orman: Oh, wow, yeah, nice call back.

Jason Hine: Thank you. I listen.

Rob Orman: So a friend of mine helped me develop another decision-making heuristic, which is that anything new you take on, is it going to be worth the time that you are taking away from other things? And what he said specifically, said it was this one project he said, okay, this is an amazing project that, I’m sure you’ll kill it, before you jump in, will it be worth the time you’re not spending with your family to do this project? And like, whoa, whoa, whoa. Because we chase the sand or we chase the thing. The answer is yes, then you do it. If the answer is no, then don’t and the answer to that was no. I couldn’t believe it, it was something I’ve been thinking about for so long. So it’s like, you know, it’s not worth it. It’s not in the long run.

Jason Hine: Yeah, that’s a fantastic litmus test and I mean, it’s a harsh one in its own reality because very few are gonna, um you’re gonna answer yes to you, right? Cause are we ever really willing to openly state this is worth my ambition to take away time from my family? But I think, you know, taking that with a grain of sand or a grain of salt about what this is actually going to cost you is very valuable. Alright but if I can, I want to bring it to a little bit more brass tacks. We’ve been talking almost a little, a little metacognitive here today, and I want to talk to you about burnout.

Rob Orman: Okay.

Jason Hine: So we talked a little bit, you know, briefly superficial level in the beginning, but we know in emergency medicine, we’re working harder, in worse conditions than we really probably have ever done before.

Rob Orman: Yeah.

Jason Hine: Whether it’s borders, psychiatric holds, for me, sometimes administrative red tape, the invasion of the corporate medical groups. There’s almost too many reasons to mention why a clinician can feel burnt out. So, how do you Rob? How do you help a clinician out of that hole? Cause it really can feel like a hole when you’re going in to do work that you’ve worked so hard to get proficient at, spent years, and so much money to get the ability to execute this job, and now, you’re starting to resent it. That’s a hole that someone’s in. So, how do you help them regain themselves? And really, their love for their work.

Rob Orman: I love the description of the hole or the metaphor of the hole. It’s so true. I, you know, I had three burnouts in my career, and it felt like I was just drowning. You know, just below the water taking on the water and it’s uh, it’s hard and it’s doable and it doesn’t feel doable when you’re feeling it. And I’ll say for, you know you, you mentioned a whole bunch of things, a lot of them were systems issues.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: And that’s, I mean really in the long term as where things got to be fixed, business systems. But that’s a hardship to turn around. There’s also the professional realm, there’s the personal realm. All three of those things play into burnout.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: And you know. What you said is common with a lot of clinicians, but nobody comes to burnout or frustration with the same recipe. And really the simple question is, I mean it’s simple and complex, the simple question is, what is it about your current situation that needs to change? And is that within your control? Is there an aspect of that that is in your control? And what’s one step you can take to improve that? That is a deep dive into each person and much of what I do each day is help individual docs navigate this. We pick, we pick one stressor. Now you, I mean, you mentioned a… little thing. Pick one stressor. Because you have to start at one point. You know, it’s like if you try to juggle 100 balls at once, it’s going to be hard. You just start with one.

Jason Hine: Yeah. Toss, toss the one ball up and down. Focus there, okay.

Rob Orman: Yeah, right. There’s so much. So, what are commonalities for docs? What are things that are stressful? There’s EMR, lack of recovery and recharging. There’s moral injury, where you repeatedly see in a part of a system where people are treated worse than they deserve, where you’re working contrary to your values. Collegiality, decay, friction. There is lack of autonomy, overwork, overwhelm. There’s all of the, all of that systemic stuff that you were talking about, I mean that’s a whole nother cargo train. Coming down the track.

Jason Hine: Miles long. Miles long, yeah.

Rob Orman: And you know what’s surprising, yet not surprisingly common with docs that it contributes to work dissatisfaction. Which, let’s just call that for the moment, is underappreciation. Underappreciation by patients, by leadership, and sometimes peers. And right, like there’s this brief window during peak COVID, when the world was giving emergency medicine this great big hug, and including consultants and in most places,

Jason Hine: From their homes.

Rob Orman: hospital leaders, from their homes, yeah right. Thank you for being there. Uh, and that’s done. So the question is, what can you do about this stuff? I mean it’s, if there is nothing that you can do about any of it, well, that leads to hopelessness, and that leads to despair. So where can you find agency in your situation? And I mentioned the three domains before that are important when you’re talking about managing or mitigating or prophylaxis burnout, that’s the ideal, to prophylaxis personal professional systems. And first focus on your relationships, what can you do there, to make sure that those are a continuing source of joy, that those are continually supported: sleep, health, fitness, all of those things for self-care, for personal care.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: And, well, let me, let me go back to the personal realm. We’re talking about agency and that’s what it all comes down to is, where do you have control? Where do you have agency? So, in the personal realm, I mean it’s gangbusters. If you want to, if you want to increase throughput through your Ed, you could do it right on the person. You could do it, but it would it’s a heavy lift.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: And there’s a whole bunch of people, and there’s only so much you can control there,

Jason Hine: By yourself. Yeah.

Rob Orman: Yeah, there’s only so much that Jay can do, in this. If you want to start scheduling monthly date nights. You’ve got, I mean you’ve got, extraordinary agency there.

Jason Hine: Yeah.

Rob Orman: It’s like you’re like, you’re from Krypton and you’re now you’re here with this little son, you’ve got this superpower. So in the personal realm, that tree has the most agency. That’s where your foundation for everything is. On the professional realm, there’s less, but it’s still there, right? So I had a client who, who wanted to leave medicine and you know, I know all these stories, I have asked permission if I could share them so.

Jason Hine: Sure, it is not an uncommon theme obviously.

Rob Orman: Yeah, right. And their main thing was, you know, nobody appreciates anyone. It just sucks. This sucks. Nobody’s grateful, just this is this why, why would I even work in this place? And so what they actually came to coaching for was career change, so I want you to help me find another career and what else can I do?

Jason Hine: What else can I do, wow.

Rob Orman: And I actually I don’t, I specifically don’t do that kind of work. That’s not, I say, if a doc wants to stay in medicine and make that joyous, great, I’m there. If you want to find career change, I will refer you to somebody else because that’s not what I want to do. So I said, well before I send you someone else.

Jason Hine: Let’s dissect this a little bit. Yeah.

Rob Orman: Let’s see what we can do. But this is, what a great challenge here that the challenge was nobody appreciates anyone. What it would seem like you don’t have any agency there because you can’t make people appreciate you cannot control the thoughts or actions of others?

Jason Hine: Right.

Rob Orman: So what can you do? All you can do is be attentive to when it happens, be present for when it happens, and act in a way that’s worthy of appreciation. So I learned this from my mentor or one of my mentors years ago, and it is. It was transformative for me, and it’s like finding the golden ticket in a chocolate bar. Okay.

Jason Hine: You have peaked my interest.

Rob Orman: I gave her this experiment, and you may have heard, I’ve talked about this in other forms before, but they took this or she took this to such an extreme. I said next shift, when you go in, I want you to start the day with this mantra. I’m open to accepting gratitude from my patients and staff. That’s it. That’s it. I’m open to accepting gratitude for my patients and staff. And I could see, I could see the wheels turning. I said, wait a second, let’s talk about what this means. I don’t want you to just say it. I want you to be like a radio telescope, like a 50 Dish Radio telescope in the middle of the desert, every dish is just super sensitive waiting for it, like this is it.

Jason Hine: For that gratitude, to pick up the gratitude you’re saying.

Rob Orman: Yes, pick it up. You’re ready to pounce. So let’s just see, let’s just see what happens. Comes back a couple weeks later. Just, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa. I can’t believe all the gratitude that was happening there. There was so much. Because in the normal flow of our day. We just let it roll off or we dismiss it or we don’t really attend to it. You know, we definitely attend to somebody yelling at us on the phone, but we don’t attend to that gratitude. And so many patient interactions or staff interactions or even consultant interactions have that woven into it. So, when that moment happens, I’m open to accepting it. It’s like, oh, let me pause, let me present. You’re welcome, it was a real, real joy taking care of you. That is good for the patient because their gratitude has been acknowledged and it also feeds you. And so yeah, so that started building. And then what she started doing was once when she would hear gratitude for someone else, she’d pull that person into the room.

Jason Hine: Ah, she sucked others. Yeah, she brought their ears up to it, made them aware of it, okay.

Rob Orman: Yeah, so then and then it just started snowballing and there were many, many, many steps. But eventually, this led to a culture change in that emergency department where people expressed gratitude and people were open to gratitude, and it was really incredible. It was just her finding that agency and just it’s like a, it’s like a catalyst, you know.

Jason Hine: Yeah, right.

Rob Orman: She was the catalyst and just expanded it.

Jason Hine: I love that, that sort of analogy to that too. That story starts out so simply and I don’t know if you got an eye roll from her initially when you suggested it, but some people might just say ohh, come on, you know, like I’m gonna be open to accepting gratitude like.

Rob Orman: Total eye roll, oh, her eyes were looking at her occiput right?

Jason Hine: Right. And then, but you buy in just a little bit. She bought in a little bit, you know. Rob told me to do something to do it, and I noticed that that family member said thank you where, you know, even when you said be deserving of appreciation. Like simple things you say, the patient asks for a blanket sometimes I’ll blow, I gotta blow that off, you know I got to go check on that other person. It takes 30 seconds. You know, you go get the one blanket, you give it to the patient and they appreciate that little thing. And that catalyst, like you said it, it’s spreads, you know the negativity that can exist spreads like wildfire as well, and it probably has less of a grade or grain against it, but positivity can do that as well. So I love that story.

Rob Orman: When you’re talking about negativity spreading, I was talking with my friend, the psychotherapist, yesterday about this and we’re talking about support groups. I mean, it was a very random conversation, and he said, yeah, you know, sometimes you know, you know, there’s forums where Ed Docs can vent and they’re like, which is sort of this online support group, and they said, “yeah, you know, support groups can be great so that you feel that you’re not alone and you have this sense of community.” One of the challenges is that it tends to get brought down to the lowest common denominator. And that negativity at uh, I mean this is kind of outside the scope of this interview a little bit, but that negativity can become equally, even more infectious than the positivity, right? I mean, our brains are just naturally wired to latch on to that.

Jason Hine: Yeah. And I think there’s an element of almost like pessimism, maybe or, you know, certainly we’re always accused. And I think it’s true, our dry sense of humor, which we use to survive the circumstances in which we live has the potential to become more than that, right, and become pejorative towards patients, towards staff, and negativity is kind of right under the skin in us in some ways because it’s adaptive, right to allow us to exist in the environment we do. But when we become, you know, fuel for the fire and a host in which the disease can spread. That’s when it becomes a problem.

Rob Orman: I’m gonna touch on something you just said. And you said, you know, when you’re, like, speaking ill about patients, etcetera, which is so common. You know, you kind of get like ohh, this freaking guy, this, that, and the other thing. One of the hallmarks of burnout is depersonalization, and we see this behavior as just kind of, you know, part of our coping and we’ve got the, yes, the gallows humor that’s, you know, that’s this, that’s this part and partial the job. But when you start really insulting patients and it’s kind of hard not to when you’re overwhelmed by you know, like the 17th meth-induced psychosis of the day.

Jason Hine: Right. Right, and it’s easy, you just like piggyback on it, you know, like the nurse will put something silly in the in the triage, like patients here for four months of belly pain, like, oh, my God, wouldn’t you know? Four, what are you doing? And you just buy it and you jump on top.

Rob Orman: Right. Yeah, so that, there’s a hyperacute burnout inventory. There’s a, you know, there’s a multi-question burnout inventory that has been distilled down to two questions. I mean, amazingly said, what’s isn’t that like, it’s not even like an emergency doc, maybe, and maybe it was an emergency doc that did that cause that’s, like, such a thing to do?

Jason Hine: Yeah, yeah, like, it’s just the two questions.

Rob Orman: What are the two questions and you know one is, what you’d expect is, like you know, I feel burned out with my job. Okay, yeah, the other is, I feel more callous towards people since I started this job, which is depersonalization or cynicism. And I think it is wise to be attentive to that when you do that, not that you know, need to self-flagellate, or like, I’m doing this, I’m a bad person. No, I have done that 10s of thousands of times, and guaranteed,

Jason Hine: Right.

Rob Orman: I was also burnt out many times and I’m not saying that if you do that you’re burnt out. But I’m saying that be aware of when that is happening and just take a little self-inventory on what’s going on with you, how are you feeling? What’s going on with work and could that be a sign of something else? Do I need to pay attention to shifting how I approach work? How do I recharge? I mean, really, what am I doing, what’s my shift distribution and structure? What do I need to pay attention to so that I can recover and come here fresh and compassionate? Which is what we all want to be, when we’re going to work.

Jason Hine: Right yeah, that’s fair and I like that idea and it’s hard to not, right? There’s a part of it in our culture. It’s part of almost survivalism, but aborting that one, it’s becoming like we talked about in the beginning, it’s maladaptive when you get down that road and it’s really becoming the prominent feature or means of communicating or even thinking about people you’re supposed to be caring for, and then it’s time to pump the brakes and change directions.

Rob Orman: Oh, actually I want to make a little course correction on something you just said.

Jason Hine: Okay.

Rob Orman: So, the aborting it, so that you can abort the behavior. But you don’t have to abort or like, focus on aborting what’s going on inside. You can, you definitely can, but at first, just attend to it. You know, slow things down, and lean in to what’s going on. Don’t have to, you don’t have to shove it away. We’re, I mean, we’re so good at that at. Just kind of packing it away in this endless storage locker. We can just pack away things into it. It’s not endless. Yeah, I think that we’re saying the same thing, but I just want you know listeners to a) not self-flagellate because we have strong enough inner critics as it is, not self-flagellate because you’re doing this or thinking. This is totally natural for this to happen, just be aware of it and sit with it for a moment.

Jason Hine: That’s fair. Alright, well, that was a great sort of behind the curtain on how you think of people who are experiencing burnout and how you help get them through that. I love the idea of sort of starting, and I don’t know if you use the term, in your coaching, the circle of influence. But, I imagine that that comes into play like you, you use the term agency. Where do you have agency? Where can you affect change? So take a catalog of the things in your work that drag you nuts that make you not want to continue to do the work you do, and which of those live within that circle of influence? Which ones do you have the ability to manipulate and in your story, simple things, appreciation, and um, knowing that you have to buy in. You’re not going through the motions in doing so, but you’re truly investing in like this individual who really found those areas of appreciation and then spread it and was a catalyst to change in the department. Coming back a little bit. You know, we started this conversation with the analogy about the barrel and I mentioned in brief that I like a full barrel. It’s just kind of how I tick. It’s something that I, gives me satisfaction in life and so of course I want to be efficient and low stress, which are, you know, sometimes that odds with each other, but not definitely. But like most highly productive people, so I bought David Allen’s, Getting Things Done, and really adapted that or adopted it into my life in a way that works for me. So Rob, do you recommend people who are looking to get organized use that or do you have a means to help them sort of organize and destress their lives?

Rob Orman: Let’s just talk about getting things done, for a minute.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: I personally find that methodology so overwhelming, you know. I have, I have, my own system, which is evolving from that, it’s been evolving for a while. You know, I don’t know that there’s a particular system or approach or pop psychology or organizational book that I have found a truly transformational transformative change across a wide swath of people.

Jason Hine: Hmm, okay.

Rob Orman: You know, changing your thinking and approach to life or examining it, not even differently, but simply examining it, probably higher yield.

Jason Hine: Okay, interesting.

Rob Orman: One book that I’ve recommended to many clients, and friends for that matter, is 4000 Weeks Time Management for Mortals. And there’s nothing in that book that you won’t have seen before, but it is a kind of book that you keep coming back to. And, it just puts things in such great perspective. And, as far as a simple tool to get things done, without jumping into the full getting things done methodology, I love Todoist. And, I mean for me it allows me to have this inbox and getting things done right, that’s the key is to have this the intake of your ideas right to capture, capture ideas. So I use Todoist to capture my ideas, and then set them as tasks and for me it’s, I mean I have, I have other things in my system, but that’s a, that’s what I think is the highest yield is alright, I’ve got this idea, when do I need to actualize it? And you know that you know, kind of the due, defer, delete, et cetera. All that, I think that’s, is that GTD, Getting Things Done?

Jason Hine: Yeah, generally, yep. If you can do it in 2 minutes to do it. If not, then it’s your action or you can send it to somebody else, yeah.

Rob Orman: Yeah. And so, it’s funny I was having a conversation with someone, yesterday who is a Getting Things Done expert, and they said, oh, I need you to do this, and it would have taken me 30 seconds in that conversation. And so I pick up my Todoist and I put that in my inbox and they said what are you doing, I said oh I’m putting in my Todoist, they said do it right now! Anyway, so for most people, like a couple of high yield things. I’d say more people than not have massively overlook, overcrowded inboxes, e-mail inboxes you know, 30,000 emails.

Jason Hine: Yeah, my wife, I can’t, I can’t look at it.

Rob Orman: So declaring email bankruptcy, incredibly powerful.

Jason Hine: Okay.

Rob Orman: You just go back, you go back a couple of months and save those emails and everything before that, just make a folder, put it, put it in the archive.

Jason Hine: Yeah, put them away.

Rob Orman: Put them away. Yep. Having defined times and methodology to interact with email rather than just, you know hitting it without intent, like okay as I enter this email, I’m going to be making these decisions like this is my time to make decisions and not just, oh let me see what’s come up in my e-mail. Turn off the freaking email notifications on your phone. Like seriously, there is I don’t, I have never received, I may, I might be an outlier, but I’ve never received an email that was so critical it could not wait until the next cycle that I looked at my email.

Jason Hine: Sure, yeah.

Rob Orman: And that, the email notification of the phone, just completely useless.

Jason Hine: Turn it off. I am imagining you’re going to put the same kibosh on smart devices and watches. Things that are going to just remind you constantly of their existence.

Rob Orman: Yeah, you know, like my wife has an Apple Watch. It’s incredible as a, you know, like a health tracker and all this stuff. But, you know, she works for Hippo and she’s on Slack, and so she gets Slack notifications all the time. She gets phone calls, she gets e-mail, she gets texts, like it’s always notifying. And it’s kind of, ah, so, you know, I don’t want to sound like a Luddite, I think it’s great technology, but I think that aspect of it is not a level up. I’m personally, if I were to wear a watch, I want to wear an analog watch. If I had a digital watch, I’d probably have one of the old calculator watches on, like that.

Jason Hine: Fair, fair. I think the point is super important to just highlight again is the idea of like designating time and not having your mind be interrupted every 5, 10, 15 minutes. But if you take, it’s going to be different, you know, different strokes for different folks because of their role, whether it’s admin or just, you know clinician, or whatever they do in their line of work and home life, it will dictate how frequently that check has to happen, but, man, it’d be a lot better if you say every three hours, I’m gonna sit down, I’ll hit my emails, and I can do all of them rather than every 15 minutes, I’m gonna get halfway through an e-mail and then, sorry, honey, what were you saying? I’ll get you know, get back to that, so I love that sort of fits and spurts rather than constant drip. And the idea of, yeah, am I ready to take my email notification app off my phone. I don’t know. I have to digest that one a little bit more but to the idea of Getting Things Done or Todoist, one of the things that’s so valuable for me and I just curious your thoughts on it or if you would agree is, this, you know, they called the artist stress free productivity, but you just need a place to put stuff, right? If your mind is swimming again and again and again over an idea, I got an email that checks my buddy and you think about 6 times that day. It’s just, now you’ve increased the amount of work that your brain is doing in the background energy consumption of it. Where if you could put it on an app or you put it in a index card in your pocket, it’s there, you check it and you, you take care of it when the time comes and it’s out of your brain. That to-do list has built itself or you’ve built it and you can focus on the moment.

Rob Orman: Oh my gosh. Wow, way to save the best for last. That’s the mail in that check to my buddy. So, I gotta tell you this Todoist story. So you, you saw my puppy when he came in here at the beginning of the interview and I was like , this is the strangest thing you know, I’ve got so much to do during the day, and as do we all. And I was kind of stressing that I hadn’t been training him to walk on a leash. And so I hadn’t been taking him for walks. And I mean, we have a big backyard that can run and play around in, but you know, we’ll take him for a walk and have him, be able to be leash trained and all this. But I wasn’t doing it, I wasn’t doing it, I was like ah, you know, it’s just I don’t know. So, when I started using Todoist, I put that as a task.

Jason Hine: Sure.

Rob Orman: Start, leash training. And then I was thinking, okay, what day, on what day can I do this? And I just hopped it in there and then that basically, okay on this day, oh alright well this block in this afternoon, that’s the 20 minutes I’m going to do that.

Jason Hine: Yeah, take care of it. Yeah.

Rob Orman: Yeah, it just totally changed it and it was amazing how much just consternation and stress and energy was taking not doing it. Right, it was taking, so it was taking, it took so much more energy to not do it.

Jason Hine: Think about it, six times an hour, I’m a bad pet owner. Yeah, yeah, that stress.

Rob Orman: That’s so true. Like I look at that dog, I feel so guilty and so, and now we go on little walks. And now our other dog is super pissed because he has to watch while I’m leash training this dog for that, anyway. But, that’s a whole nother story that Todoist isn’t going to fix.

Jason Hine: Now that’s something else for another time. But Rob, I have loved, loved, loved, loved picking your brain on this topic matter. I think there’s been so much to unpackage here. We may have to, we may have to have you come back. We may have to break this up into smaller installments. But there is so much goodness that has come from my chat with you, that’s going to affect the way that I interact with my staff, my family, the way I think about life as a whole man. That’s a lot that you accomplished, that we accomplished in this conversation. So thank you so much for joining me for this and letting me pick your brain.

Rob Orman: Oh, I well, I received that gratitude with a full open heart. And let me, let me send back to you that you have taught me a lot over the years as well and I think so. This is a, this is a real mutual appreciation and symbiotic relationship.

Jason Hine: Fantastic. Alright, thank you so much for listening. And until next time.

Work-Life Balance | The Basics

“There’s no such thing as work-life balance. It is all life. The balance has to be within you.”

If you want to think about your life and its balance, you may find it easiest to start by breaking down your life into quadrants, specifically Work, Health, Play, and Love. By doing this, one can compare the attention each quadrant is getting to determine if they need more or less of it.

By comparing these quadrants, you may ask yourself: which is getting a lot of attention, and which needs more? This method of organization was inspired by the book, Designing Your Life by Bill Burnett and Dave Evans.

A trap that is easy to fall into, especially as a clinician, is that your work quadrant takes up a lot of your life. Clinicians often feel as though nothing will stop them from getting to their shift, creating a boundary around their work. Compared to work, the other quadrants of life do not get the same level of protection. Because of those relying on EM clinicians (colleagues, nurses, patients), this protection is natural- but why don’t we (or can’t we) protect the other parts of our lives as important or more so in producing happiness in us?

Many studies show what truly makes a good, happy life are quality relationships. At the end of the day, no matter someone’s income, social class, or IQ, the relationships they make with others will impact their lives more. Outside of work, to truly experience a fulfilling life, it is mandatory that you are attentive to the other quadrants that need more attention. Because of the overpowering role work plays for most people, it is important to undergo self-reflection and ask yourself:

Am I putting the same energy into health, play, and love?

Most of us are oversubscribed to work in one way or another. This may take form in either the time we put into it or the stress that is attached to it.

How to leave work at work and not bring your work experience home

Creating a Balance

It is important to find the balance between not dichotomizing and existing on a different plane, but also leaving the Emergency Department at work. The impact and significance of the transition from either your shift to your home or going from your home to your shift is massive in creating a buffer between work and life.

Dialing in on the work-to-home transition, there are long-term and short-term aspects. Dr. Orman describes a practice for all to try after a long day of work, specifically focusing on the short-term aspect.

First, start by processing your day. This can be on your commute back home, whether you are biking, driving, or running. During this time, either listen to music, a podcast, or just silence. After you park your car or lock the bike up, take 5 minutes and just sit. Take deep breaths, with longer inhales than your exhales, deep in the nose, and slowly out through pursed lips.

Next, once you feel like things are calmer and slowed down, walk through your day. Ask yourself:

What did I see?

What did I feel?

What went well, any great moments?

What is one thing I could have done better?

How am I going to grow from this?

Overall, you are just actively reflecting on and processing your day; and you could even pull out your journal!

Finally, imagine all of that stuff gets condensed in a balloon. The balloon is filled with mixed emotions and stress from your busy workday. You visualize yourself cutting the string, snip. All of the stressors float away, and boom, you’re ready to go into your home. This practice is a form of de-escalation and is key to creating a healthy transition from your workplace to your home.

What about the Cases that Ruminate with you?

After a busy day of work, it may be difficult to stop yourself from thinking back on past decisions. This may include confusion you had over a patient’s symptoms or a mysterious diagnosis. It is important to learn coping mechanisms to move past the repetitive thoughts and debates in your head. Try this practice, described by Dr. Orman:

First, while at work, identify pivotal moments where you may later on ruminate about it after your work day. Take a minute to pause and think to yourself:

Dear Future Self,

At this moment, I am making the best decision based on the information I have.

Every time you have a pivotal moment, stop and say this to yourself. As you say it more and more, it will become more comfortable and build mental muscle. It will help keep your future self from Monday morning quarterbacking or ruminating on a case.

Action by action, bit by bit, integrating these methods into your daily life will help ease the transition of work to life. After a long tedious night shift, it is easy to find watching TV a coping mechanisms for the constant brain pull of the shift’s successes and failures. This passive attempt to de-escalate your brain overtime hurts you by creating a pattern of pushing your thoughts back and away, wasting time, and pushing sleep back. This pattern will create more physical and physiological stress in the long run.

By just creating 5 minutes of active de-escalation, you will not have to waste 4 hours watching TV in an attempt to passively de-escalate your brain after a hectic day.

Life as a Barrel Analogy

This analogy is a helpful exercise used by Jason to deal with the balance of the four elements of life, mentioned earlier.

First, imagine a barrel. This barrel represents your life. You can fill it however you choose. You begin by putting the big, top priority items in first as they take up a lot of space. These are the boulders and could be your family, career, mental or physical health, or a passion you could not live without.

Next, ask yourself:

Is my barrel full?

No, at this point, you decide to add rocks- hobbies, side projects at work, etc. You again ask if your barrel is full. Again, the answer is No. You add in sand to fill in the spaces between the boulders and rocks. Depending on the person and the life they like to live, some may want empty space to reflect, room to breathe, and add some spontaneity. Or, others may want their barrel filled completely, living a full and as active life as possible.

Finally, your barrel is completely full, unless you decide to crack a couple beers and pour them in… Which is just a reminder- There is always room for a couple beers.

The KEY to this analogy is to give the boulders value. Once you identify your boulders, nothing can interrupt them, as they are most important to you. If you do not label them, it is easy to fall prey to prioritizing sand on a regular basis. Keep track of the amount of boulders you have, so if you discover you have too many large items, try narrowing them down. Ask yourself, what can be put on the shelf for a while?

Combatting Overwhelm

When attempting to combat overwhelm, try tying this analogy to your practice:

First, list out all of the boulders, rocks, sand, and the total mishmash of things in your barrel. This attempts to break your overwhelm and the barrel itself down. Ask yourself:

What are my boulders and how many are at play?

What boulders are non-negotiable?

What can be put to rest for a while?

What can be removed?

What is it giving and or costing you?

By asking yourself these simple questions, it makes you realize what you value most, and what you need to spend more time and energy on!

How to Balance and Handle the Urgency of Work in Your Life

Looking through the lens of a Global Perspective

Looking at the urgency of your life in a global perspective helps you take a step back and realize what you value most. Think back to the four quadrants of life:

By channeling these four components of your life, attempt to create a balance between them. It will not be down the middle, as some will require more energy for different amounts of time. By comparing these quadrants, you may notice that work is taking up a lot of energy in your life. Ask yourself:

How is this fitting in the rest of my life?

What is this going to look like in the long term?

This overarching perspective helps you take a step back and think of the long term effects of putting too much energy into one quadrant. This global perspective makes you realize the small things that are causing you so much overwhelm may not be as big of a deal as you are making them seem in the short term.

Balancing Trade Offs

A decision making heuristic to ask yourself before taking a new project on is:

Is it going to be worth the time that you are taking away from other things?

Think about the long term, and if the answer is yes, do it. If not, it is not worth it.

How to Deal with Burnout as a Clinician

Three Factors Leading to Burnout

As a clinician, the hours are long and rigorous, causing burnout to occur. The three most common factors leading to burnout and work dissatisfaction are:

1. Business/Admin Systems

2. Professional Realm

3. Personal Realm

All three factors impact the feeling of burnout in your life to varying degrees. Whether it is a feeling of under appreciation from your patients or peers or the exhaustion from dealing with bureaucratic red tape, both negatively affect your mental state.

Taking Charge and Creating Agency

To combat burnout, we have to really understand it and where it is coming from. To understand your burnout, ask yourself:

What is it about your current situation that needs to change?

Is it in your control?

This helps you break down the stress and burnout in your life, little by little. Once you have a better understanding of your dissatisfaction and burnout, ask yourself:

What can you do about it?

What is one step you can take to improve that?

Where can you find agency in your situation?

Finding your agency in all realms of your life (not just work) are essential to battle burnout. In your personal realm, it is all up to you, you have the agency over yourself. In your professional realm, it is much harder to have complete agency, but it is still present.

For example, Dr. Orman discusses a time when his doctor friend was feeling very underappreciated. They felt as if they had no agency in the situation because they could not make people appreciate them and they could not control the thoughts or actions of others. Rather simply seeing the situation as hopeless, the doctor needed to find the agency they had, no matter how small, in the situation. Dr. Orman said to be present when this situation happens, and act in a way that is worthy of appreciation.

The GOLDEN TICKET in this example was to not only be more attentive and ready for gratitude, but also to say to yourself before work:

I am open to accepting gratitude from my patients and staff.

Immediately, the doctor started to notice and pick up on all the gratitude happening in their daily life. Small pockets of gratitude are so easy to miss, but just by setting the intention, they became apparent in large quantities.

The doctor went the extra mile to the point where when they heard any gratitude at the workplace occur, they pulled others into it and shared it with them. When gratitude happened, all involved parties were made aware. This small change led to a whole Emergency Department culture change. Everyone was expressing gratitude and open to it. The doctor was able to find their agency in the situation and became a catalyst for the entire department.

Battling Negativity

It is so easy to give into negativity as the human brain is naturally wired to latch onto it. In the workplace as a clinician, it is easy to complain about a patient or colleague and feed into the negativity, especially as a doctor suffering from burnout. There are two helpful burnout inventory questions to consider:

1. Do I feel burned out?

2. Do I feel more callus towards people since I started this job?

In answering these questions you see negatively and burnout are kindred spirits. You may notice that you feel more cynicism or depersonalization since you have started your job, leading to a cycle of negativity about others and about yourself. Admitting to yourself that the negativity you are feeling is caused by burnout or vice versa, is a step out of the hole of burnout.

When feeling this way, take a self-inventory about what is really going on- the true root of your negativity. Consider to yourself:

What’s going on with work and how can that be a sign of something else?

Do I need to pay attention to shifting how I approach work?

What do I need to pay attention to so that I can recover and come here fresh and compassionate?

When answering these questions, cycle back to some of the structures and recommendations from above for ways to clearly see your life’s quadrants, areas of overfocus and areas needing refocusing, and how to take the first steps to combating your burnout through small areas of agency.

Organization Necessities and Recommendations to Help Destress Your Life

Helpful Organization Resources

A few organizational resources recommended by Dr. Hine and Dr. Orman are Getting Things Done (GTD) by David Allen, 4000 Weeks Time Management for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman, and Todoist. The book, 4000 Weeks Time Management for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman is a book that Dr. Orman constantly comes back to throughout his life to help maintain a healthy perspective.

An online resource used by Dr. Orman is Todoist. Todoist is able to capture your ideas, set them as tasks, and overall organizes them by actualizing the ideas.

Life Style Organizational Recommendations

A huge stressor in our lives are constant notifications. At any point of the day, on any device, notifications are always alerting you. One method to battle this constant nagging is by creating defined times to check your alerts. Whether it is your email or Slack, create a methodology to interact with your email rather than just checking them randomly with no intent. Try removing your notifications on your apps, which are constantly reminding you of their existence. Decide on designated times to check these apps, emails, or sites, otherwise they will continually cause interruptions.

In your life, your mind is constantly remembering things you have to do, whether it is a text you need to send, or even a reminder to walk your dog. This increases the amount of work your brain is doing in the background. It takes so much energy to not do a task and continually think about doing it, rather than just completing the task in the first place.

Try taking advantage of Todoist or GTD as they may act as a place to literally just put the stressor. You know that you will complete it when you have the time, but at this moment, it is out of your brain and on the app or index card in your back pocket. Now, you can focus on the moment.

Practicing procedures can be tough. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting in your skill maintenance. Procedural training can and should be easy, done in your home or department, and work within your schedule. We want you to be confident and competent clinicians, and we have the tools to help.