For a long time, medicine has been a “good ol’ boys club” and in the areas of gender inequity, sexism, and patriarchy, this old way of thinking in medicine really does fall on the wrong side of history. Thankfully, we have made progress away from “the way things used to be,” but so much more work needs to be done. With the lay press and productions like the Barbie movie bringing patriarchy back into the spotlight, we thought it would be a good time to discuss gender (in)equity and Emergency Medicine mansplaining.

In this guest podcast, we have Dr. Kimon Ioannides talking on Mansplaining in the ED, a talk he gave at AAEM Scientific Assembly.

Kimon Ioannides: And I’m embarrassed to say that that particular doctor was myself. So I’m not saying that all men. Are bad. Yes, some men are bad. It’s not women’s job to fix our mistakes or even to point out our mistakes.

Jason Hine: Hello and welcome back to the SimKit podcast. Today, we’re going to be talking about emergency medicine, mansplaining and gender equity in the emergency department. We are joined by a special guest of former co-resident of mine came on to talk about his experience in this realm. Given the current climate with popular movies like Barbie addressing the patriarchy and gender equity, I thought that this was an important topic to discuss, and even though this presentation and Q&A were recorded a couple of years ago, the topics and materials addressed in it are no less pressing now, sadly, than they were back then, and this is a very tricky topic matter to discuss and even in doing so, we recognize that this conversation is between two cis white men talking about gender equity. So we do plan to have an additional conversation with other demographics within the care team about their experience with gender equity and inequity within the emergency department. But for now, please enjoy Kimon’s insightful reflection on where he lives and what role he has in gender equity in the emergency department and allow to be an opportunity for some self-reflection.

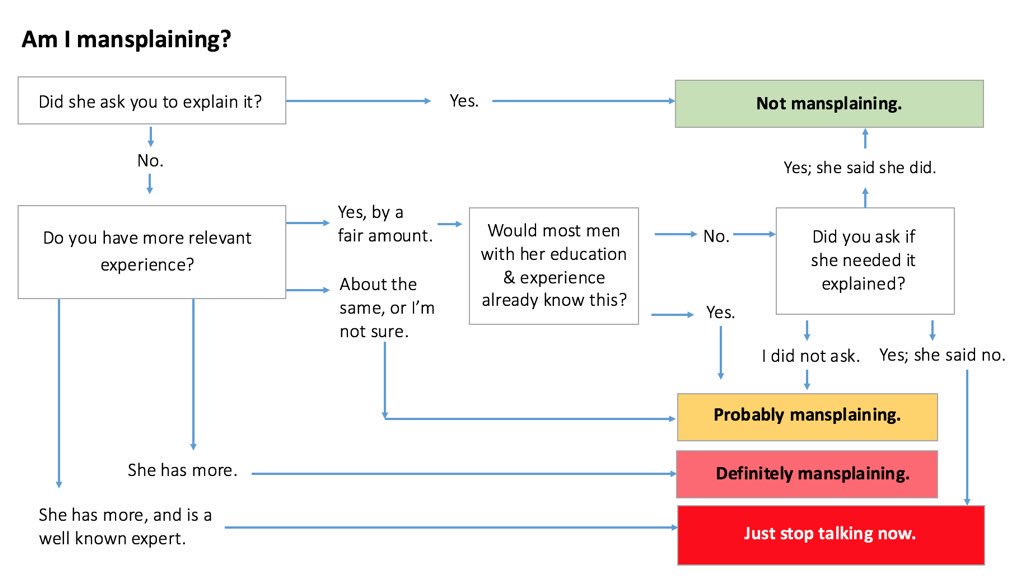

Kimon Ioannides: So hi, I’m Kimon. I do not have any disclosures, but I am here to talk about emergency mansplaining and more specifically, I want to talk about what gender equality looks like in all of our emergency departments. So let me just start off with a quick story about a doc in RED who was pretty grumpy on an overnight shift. Seemed like it kind of came into it tired not in the best place, but really ended up spending, you know, a good chunk of the night just kind of complaining about patients, consultants, nurses and just being kind of difficult to be around. I remember in particular interaction between this stock and a nurse about a patient who needed a pelvic exam but wasn’t yet in a pelvic bed, and just kind of like, not quite berating, but just being difficult and unpleasant with this particular nurse about why the patient wasn’t already in a pelvic bed. And I’m embarrassed to say that that particular doctor was myself. A lot of people tolerated my behavior on that shift. When I went back and asked for forgiveness and apologized, they forgave me, but the whole interaction really got me thinking about like you know, would a woman have gotten away with the behavior that I engaged in? And you know, is this something that, you know, I I certainly need to apologize and make amends for for that particular night and repair those relationships. But more broadly, like, what can I do as a man? What should I do as a man to kind of improve gender equality and so obviously the first step is don’t be a jerk. That seems pretty obvious, but I think there’s really a lot more to you know what, as as men, we can and should do to improve gender equality. So I have a couple of specific learning objectives that we’re going to focus on today #1 we’re going to talk about some modern ideas about feminism, gender and bias, and apply them to actual clinical practice in the Ed. And #2 I want to develop some specific behaviors that as men we can exhibit to support a fair environment for patients and providers of all genders. And I do want to acknowledge that gender is not a binary I’m speaking to, you know, self-identified men in this talk, but that does not mean that I’m not speaking to everybody else. And I do think that there are elements of this conversation that we all need to be open to. So before I move on, I want to be explicit about a couple of things that are not my learning objectives. I’m not saying that all men are bad. Yes, some men are bad. Me too has made that very apparent. Also, I’m not trying to say that I’m not sexist. I probably have been and probably am in some ways. Sexism really pervades our culture, and as a cisgender, heterosexual white male, I have a lot to learn and a lot to. Move upon but one of the key points that I’m going to come back to a couple of times in this talk is that the men who are persistently bad are the folks that that don’t acknowledge the ways in which they are sexist and the biases that they hold and take steps to repair and fix those. One more not learning objective. I’m not trying to say that emergency man’s planning is helpful or that it’s a solution. It definitely is not. But we do need to take some time to define, like what mansplaining is and you know, maybe we’ll start off with a quick quick joke here. “Where does a mansplainer go to get? Well, actually…” uh, and you know, this is like obviously a silly joke. But you know, I think that manner of speaking that taking the time to say, well, actually, you know, my perspective as a male is really privileged in this situation is a pretty common way that not only men are socialized to fall back on, but a lot of people will accommodate that unknowingly, and that ends up kind of pervading the behavior. But you know more formally. I think mansplaining is any explanation in a patronizing manner, often by a man to a woman, and commonly about a topic relating to gender. So let’s do a couple of examples here. So #1, this is a sketch from Saturday Night Live, guy saying “it must be so hard to be a woman,” so classic like. Offering a thought that’s not particularly helpful and obvious to many people in the room in kind of a A. You know, self-righteous or patronizing way. And actually Kim Goodwin put a great flow chart out on Twitter to kind of walk men through, like how to tell if you’re mansplaining. And so to just use the example from my introduction, you know, did the nurse I was working with asked me to explain you know how important it was for the patient to be in a pelvic bed? Definitely not. Do I have more relevant experience about rooming patients and getting them in pelvic beds? No, definitely. She has more. So that was definitely mansplaining. I think we should also consider another example of this particular talk. Did any woman ask me to give this talk? No. Do I have more relevant experience about dealing with gender issues? No, probably not. I think most women have more because they’ve had kind of a lifetime of having to deal with gender issues, whereas my, you know, my interest in these issues is relatively recent. That from a man’s a man’s perspective, maybe I have about the same perspective. I don’t know. Either way, I’m kind of in this yellow-orange, high risk mansplaining category. So I do want to acknowledge that I’m trying to mitigate as much as possible the mansplaining-ness of this particular talk. So why is mansplaining as a topic important to our work in the ED? I think we have to acknowledge that our work is pretty high risk for problematic gender dynamics, and I want to spell out a few reasons for that. So #1, our field is majority men, certainly that’s changing a little bit, but especially in academia and in leadership positions. Within emergency medicine, men are still the overwhelming majority. #2 you know, there are a lot of hierarchies in medicine in general, and that’s a known risk factor for harassment across multiple fields. #3, you know, both patients and providers bring with us to the ED kind of traditional gender roles and a sense of what it looks like to be a care provider as a doctor, as a nurse. And I think that can really complicate the interactions that we have when we bring these pre-existing expectations. And I think it’s especially tricky in the Ed because there’s not as much kind of pomp and circumstance about introducing ourselves, so you may have a doctor putting an IV in, or you may have a nurse, you know, making a decision or putting in an order and getting things started. And so that can create confusion when these traditional gender roles are not met. And then finally, everybody stressed out in the ED and I think that can lead to us regressing to, you know, some ingrained biases about others and can exhibit behaviors that when we’re a little more calm and in a better and a better state of mind, we would, we would be able to control. So why does this matter to me personally as a guy? I think there’s a couple of reasons. Number one, I care what my colleagues think of me and the example that I gave earlier about that overnight shift by grumpiness was accommodated. But that was really kind of embarrassing and I probably would have been confronted if I was a woman. And I was really abusing my male privilege in that situation and making my ED more unpleasant. #2 I care about my colleagues. My intern year was really not terrible. There are a lot of aspects to it that I enjoyed and I realized reflecting on that that part of that was because I had a this new concordance between the letters after my name and the sort of expectations that I had grown up with that like as a guy I should be in charge of things. I should be able to put in orders and do things and it kind of gave me a sense for what it might feel like if I’d, you know, been constantly throughout my medical training, been dealing with a discordance, I mean the role, the professional role that people expected me to play and the gender identity that I grew up with. So what makes changing all these things hard? So I’m going to introduce a couple of concepts that can help us understand that. So #1 is this idea of toxic masculinity. And this is sort of encoded set of attitudes that I think for men are ultimately rooted in insecurity that can provide guidance to us and novel situations for how to act, but can be really problematic when they involve kind of a regression to macho. #2, I want to adapt a concept from Robin D’Angelo from a book about race called white fragility to create this concept of male fragility. And to me, this is basically the idea that as men we have, you know, feel vulnerable about being told that we’re sexist and so. When someone points out something that we do, that’s problematic, we end up being really defensive about it. And that defensiveness really stops us from learning from a mistake in a way that’s super problematic and worsens the situation, even though it’s perhaps rooted in some desire to not hurt others. And then finally, I think as men, we have to recognize that it is on us to really do the work to further gender equality. It’s not women’s job to fix our mistakes or even to point out our mistakes, because that ends up putting an additional burden on them. What can men do to promote gender equality? I’m going to split this into a couple of categories, kind of big picture stuff that can affect society as a whole or our profession as a whole. And then small picture stuff we can do on a day-to-day basis. So big picture #1, I think we have to start thinking about the role that gender plays in everything that we do, every interaction that we have- every professional or personal role that we play, because the truth is that many women, and especially gender nonconforming folks, have been thinking about this throughout their lives. It’s something that’s incredibly salient to every interaction that they have, and taking the time to engage that same thoughtfulness I think will help a lot of us as men really understand the experiences that other people are having. #2, we should take the time to develop vocabulary and literacy around gender issues when you can use terms like toxic masculinity or mansplaining or microaggressions fluently, it allows us to kind of participate in conversations and puts us in a position to really make change. #3 As men, we have to be willing to accept feedback really openly and say that both explicitly and implicitly to the people around us. But we can’t expect feedback. It’s not anyone else’s job to point out our problematic behavior. That puts an additional burden on them. That’s not really fair. We have to be willing to call ourselves out. And then finally in the political sphere, but also within our profession, we have to be advocates for gender equality and allies in that struggle. And even within our field, advocating for things like maternity leave or pay transparency can help everybody. But I think particularly can help people other than men move forward in our in our profession. So the small picture things we can do on a day-to-day basis, I think men can take a leading role in mentoring and sponsoring women and those are slightly separate concepts. I think mentoring is providing advice when requested and answering questions to folks that are coming up in our in our field. Sponsoring is a little bit different and I think that involves. You know when there’s a position to open, taking the time to really consider women applicants, inviting women to give talks at grand rounds and being in a position to promote their advancement and their profession in the same way that that I think men have been doing for each other for a long time. And there was kind of an interesting NEJEM editorial that came out recently. Talking about this notion that leaders in academic medicine were worried about mentoring women because they were worried about concerns that they might be accused of sexual harassment, and to me, this really totally falls under the “don’t be a jerk” category if you’re not harassing anyone, then you’re not going to be accused of harrassment. So next small picture thing, this is something that I’ve found to be personally helpful in my work in the Ed to really take the time to introduce my colleagues with both a title and a pronoun. So for example, if I’m signing out to a woman doctor, I’ll tell my patient. Hey, you know, your CAT scan isn’t back yet. But I spoke with Doctor Jones. She’s one of our other ER doctors. She’s going to be following up on your results and she’ll come and check in with you. And I think that, you know, if there’s anything that I can do to reduce the chance that, you know, one of those doctor nurse confusion moments is going to happen I really feel like it’s incumbent on me to do that. Next thing from the small picture, making expectations really explicit, both in our colleagues and especially in our trainees, if we’re able to set out a very specific an explicit list of what we expect of each other, that puts everybody in a position to perform on the same level, and I think that particularly helps eliminate some of the like personality feedback and gendered language that ends up in a lot of our evaluations when there’s a specific rubric for how people are supposed to behave. And then finally, as men we have to call out the microaggressions that we see around us, whether it’s a sexist comment or just an awkward or or odd interaction that feels a little bit hostile, we need to point out that we’re uncomfortable with that and set the tone or contribute to setting the tone. And we shouldn’t necessarily expect to be praised or thanked for that. It’s not anyone job to thank for that, and we shouldn’t just do it if someone appears to be uncomfortable with it, if we’re not, you know, comfortable with it, then we should point that out regardless of whether or not a woman says or seems to be distressed by something that happened. So with that, I want to wrap up into some some key points. Number one, I think we all need to recognize our own sexism. That doesn’t make us a bad person and fact that puts us in a position to repair and improve ourselves. We have to take the time to think about all the interactions that we’re having in terms of how our gender identity fits into that and puts us in a position to stop abusing the privileges that we carry around with. And then finally, we need to continue to advocate for equality, and that can be things in our in our professional groups like making expectations really explicit and creating an opportunity for helpful feedback for each other, but also in the public in the public policy realm. So with that, I’ll wrap up. Thanks so much to Jason Heine for recording this to Meg Healy for her patient mentorship to my friend Jerrod Bowen for his very helpful feedback to every woman and man who’s dealt with my BS. If you want to learn more, I highly recommend the FeminEM podcast series. Recommend following Esther Chu on Twitter or you can just look up the page on microaggressions on Wikipedia. It’s a great start, please for me to reach out with questions. I’m on Twitter. I’ll be around. Thank you so much.

Jason Hine: Alright, Kimon, thank you for recording that with us here and allowing us to kind of post your content. It’s a really interesting and you know awesome topic for first of all, kudos to to taking that on as a man. I think when you sort of approach this or start thinking about doing this talk well, how were you able to overcome the barrier of this maybe is just something for women to be presenting. How did you approach that mentally?

Kimon Ioannides: Well, I guess thanks so much. First of all. Secondly, I think it’s interesting that I feel like a lot of folks have given me kudos because I kind of feel like I don’t deserve it like it feels like a basic thing. And like if a woman were presenting this topic, she probably wouldn’t necessarily get kudos for doing it as a woman. Right. So thank you. But it feels like a little bit unfair. It’s like the standards are so low for us as men that.

Jason Hine: Yeah, to actually care about the topic.

Kimon Ioannides: Yeah, but, you know, I think your question was kind of about like, how do I get over the hump of like this not being a topic for just women to present that it’s something that, like, men should talk about. And I think like for me what was helpful was just like thinking about how, how does this topic actually affect me personally? You know, how do gender dynamics stress me out? Or worry me, how do I wonder how they affect other people? and just kind of be open about some of those uncertainties that I have, but also share some things that have been like personally helpful for me.

Jason Hine: Yeah, that makes sense. I think as you know, I hear you talking about this anytime where you’re you have to develop self criticism it creates some discomfort. And as as I was listening to you, I think that’s strange for me. You know, I think a lot of ER doctors like being uncomfortable like, you know, we are often either high performing athletes or we exercise to a level where we’re uncomfortable. A critically ill patient that we don’t understand, that makes it’s uncomfortable, but it has a different feel to it. And I think this discomfort comes because there’s an internal critique and part of that critique is your unknown unknowns are very challenging. We don’t know- as you’re talking about this- we don’t necessarily even know that we’re committing these crimes or you know committing mansplaining or other inequities that way. So how would someone get over that discomfort and start to recognize where their “unknowns unknowns” lie?

Kimon Ioannides: Well, I think you you make a great point about like. Us being comfortable with uncertainty and I think we’re also comfortable with being wrong. A lot of the time, you know, we don’t necessarily get the diagnosis right, but we at least get the disposition right.

Jason Hine: Yeah, sure.

Kimon Ioannides: And and so I think that’s like a key asset that as men, ER docs we can draw on. I think accepting the discomfort, accepting that we might be wrong. But if we feel like we’re doing something wrong, just accepting that, recognizing it, not like judging ourselves for having done something wrong, but just taking the steps to change it in the future to correct it. Not sure if that’s a great answer to your question, but.

Jason Hine: No, I think it was good. I think for the the very hard and challenging part of of this for me is. Where am I doing things incorrectly and and I think it’s easier once you recognize them to fix them, right? But recognizing them is the problem, and I would love to be able to go around my department and and speak to all the the women there, nurses and docs and everyone and say if I. Act sexist. Please call me out on it, but that’s probably unrealistic, so it might have to come.

Kimon Ioannides: Or awkward for them.

Jason Hine: Right? yeah. So it might have to come internally or do you have any recommendations for people to start recognizing their first mistake?

Kimon Ioannides: So, I think you can ask other men think that that doesn’t put a burden on women, right? But, you know, if if there’s someone in your practice group or one of your colleagues, you can just ask and say, hey, like, I was wondering about the situation. It seemed like, you know, this woman was upset with how I handled it. Like, do you have a sense of whether or not there was some component of gender bias that was contributing to that right? Because other men can be critical of us as well, it’s sometimes easier to see the flaws in other. People, I think also like it, you know, it’s awkward to, like, go around everybody in your in your that’s around you and say like hey, I want feedback on this particular thing that’s a part of an identity that’s really specific for you. But I mean, if you can publicly say in a way that’s not directed to a particular person, like, hey, I’m interested in issues of you know how gender bias affect our practice. You know, I’m not. I’m not perfect. As a human, I don’t think anybody is. But you know, would anyone be interested in forming a working group of of people of all genders, to move forward on this, that opens the conversation? Maybe it’s not the people that end up coming to, you know, brunch with you to talk about it, but it allows someone to feel like, oh, hey, this is a person that’s open to this conversation and you.

Jason Hine: Right. And then you can get the feedback without targeting in a way.

Kimon Ioannides: Yeah, absolutely.

Jason Hine: And sort of the last question to sort of wrap up I think is what’s our target audience in a lot of ways? For this, so you know, some people may say that this is a lecture that’s targeted toward men and that, you know, the women listening to here may not glean a lot from it, or that we may even be wasting their time. And then the other element of that is your message may only land on the ears of the progressives, while everyone else who is not interested in the topic or not ready to be aware it’s falling on deaf ears, so how would you address those two concerns?

Kimon Ioannides: Those are great questions. So I guess there’s two questions there. So for the first part about whether or not the talk is kind of like directed to men specifically or if it’s, you know to a broader audience, I think you know the Me Too movement and the FEMINEM podcast have really opened the conversation about gender to a broader audience like, I think it’s a conversation that was happening, but was really happening amongst women in private. And so I think the fact that it’s become a public dialogue in our field and in the public press has like opened a lot of interpersonal conversations up that I’ve had the privilege to participate in. And so I think you know, yes, the talk is like kind of about men and things that that we can do but. Having that conversation be an open one that also includes women is ultimately going to have benefits for everybody. And then you know the second part that you mentioned was about, you know, how to open this kind of conversation up to folks that don’t necessarily identify a priori as being interested in the topic. And I think first of all for me, like I think I would have identified a couple of years ago as someone who was a priori interested in the topic, but I feel like there’s definitely still things that I’ve learned in the last couple of years that I’ve tried to throw into this lecture. So I think even for like a self-identified progressive person, you know this is a helpful topic to kind of think about.

Jason Hine: And I think sort of coming back to some of the things we talked about our initial question. That idea of the unknown unknowns, even if they’re not going to receive the information or embrace it necessarily to over here be part of or come to a conference as you know like AAEM and and see this being talked about it at least becomes a known unknown and eventually can work on progressing past that so. Bringing it to the table their ears are no longer deaf.

Kimon Ioannides: And it’s such a tone that, like, there are men who care about this. Yeah, yeah. And we’re supporting.

Jason Hine: I think that’s important. Man, I appreciate the talk. Thanks for taking the time to record and hope to. Have you on again? Yeah.

Kimon Ioannides: Thanks for your time. Appreciate it.

Jason Hine: Thank you for taking the time to listen to our conversation on this super super important topic and again look forward to having more conversations on the site on the same. And remember, in addition to this amazing free medical education, SimKit offers procedural training kits and rare procedures to help keep your skills sharp for when you need to perform. Check out the link at the bottom for more.

Gender Dynamics In the Emergency Department

Emergency Medicine and Medicine in general is high risk for problematic gender dynamics for a few reasons:

- The field is majority men. This has been changing as of late, which is great, but academia and leadership roles have been dominated by men.

- There are a lot of hierarchies in medicine.

- People bring in their gender biases into the work field. Many of us have biases of what it means to be a doctor or a nurse, and these preconceived notions are brought into the Department.

- The Emergency Department is stressful. Under stress people may not be as able to curb language or biases and talk with the same attention to gender equity as they may in a calm environment.

What is Mansplaining?

Merriam Webster defines Mansplaining as “to explain something to a woman in a condescending way that assumes she has no knowledge about the topic.” Kim Goodwin, however, may better encapsulate what mansplaining is through her now famous flow diagram (right).

How Do I Avoid Mansplaining?

Have you ever mansplained? If so, how do you avoid doing it again? Listen to Dr. Ioannides experiences while doing some self reflection.

What Role Do Men Play In Gender Equality In The Emergency Department?

There are several steps men can take to avoid gender inequities and mansplaining the ED.

- Think about the role that gender plays in everything we do. This may seem like a heavy lift- right up until we realize that most women and gender non-conforming people have been doing this throughout most of their lives.

- Take the time to develop vocabulary and literacy around gender issues. The ability to use terms like “toxic masculinity” “microaggressions” and “mansplaining” fluently, it puts us in a position to participate in conversations around gender equity and be involved in positive change.

- Be open to feedback, but don’t expect it. It is not a woman’s or other care teams member job to point out or correct our faults, but making yourself open to feedback in the realm of gender inequality is one of the first steps to improving gender dynamics.

- In our profession, be allies and advocates. By working with your department and hospital system as a whole on issues like pay transparency and maternity leave shows your support of gender equality in the work environment.

Summary & Key Points

- Gender dynamics and inequities are pervasive in medicine.

- The first and most challenging step, especially as a man, is to look internally and recognize your preconceptions and biases that may affect the way you interact with your care team.

- Recognize it is no one else’s responsibility to correct your faults. Making yourself open to feedback while working personally on areas of gender inequality in your work interactions is huge toward making positive change.

- Be and advocate and speak up. Being willing to recognize and call out mansplaining and microaggressions seen in the work environment is both socially tricky and hugely important in the support of a gender equal work environment.

Practicing procedures can be tough. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting in your skill maintenance. Procedural training can and should be easy, done in your home or department, and work within your schedule. We want you to be confident and competent clinicians, and we have the tools to help.

Additional Resources & Readings

1. Wiler JL, Rounds K, McGowan B, Baird J. Continuation of Gender Disparities in Pay Among Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Mar;26(3):286-292. doi: 10.1111/acem.13694. [pubmed]

2. Cydulka RK1, D’Onofrio G, Schneider S, Emerman CL, Sullivan LM. Women in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Sep;7(9):999-1007. [pubmed]

3. DeFazio CR, Cloud SD, Verni CM, Strauss JM, Yun KM, May PR, Lindstrom HA. Women in Emergency Medicine Residency Programs: An Analysis of Data From Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-approved Residency Programs. AEM Educ Train. 2017 May 4;1(3):175-178. [pubmed]

4. Briggs CQ, Gardner DM, Ryan AM. Competence-Questioning Communication and Gender: Exploring Mansplaining, Ignoring, and Interruption Behaviors. J Bus Psychol. 2023 Jan 9:1-29. [pubmed]

5. FEMinEM site