Contributors: Dillon Warr, MD and Jason Hine, MD

Status epilepticus is a clinical condition squarely in the wheelhouse of the Emergency Medicine physician. Here, we will discuss a recent article that asks an important clinical question: which induction agent should we use in RSI for those patients in status epilepticus that require intubation? We will subsequently discuss key ED management considerations for this neurologic emergency, including our approach to status epilepticus and intubation.

Practicing procedures can be tough. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting in your skill maintenance. Procedural training can and should be easy, done in your home or department, and work within your schedule. Get 10% off with coupon code SimKit10

Airway Alchemy: Status Epilepticus – Intubation and Management

Part 1: Article Review

Article

Woodward MR, Kardon A, Manners J, et al. Comparison of induction agents for rapid sequence intubation in refractory status epilepticus: A single-center retrospective analysis. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2024;25:100645. Published 2024 Jan 8. doi:10.1016/j.ebr.2024.100645 [pubmed]

Background

Airway management is an important early consideration of status epilepticus, particularly in those patients with evidence of impaired gas exchange, airway compromise, concern for elevated ICP, or refractory status epilepticus (RSE).

Classically, RSE is described as ongoing seizure activity despite the first and second line administration of benzodiazepine and an IV bolus of an anti-seizure medication (like Levitaracetam). It is the point at which it is time to pull the trigger on starting a continuous anti-seizure medication, such as midazolam or propofol. And once this gtt is started, if they haven’t already, the patient will no longer be able to maintain their airway.

There is very little evidence or guidance regarding the appropriate induction agent for RSI in the setting of status epilepticus. In theory, benzodiazepines, propofol, and ketamine have anti-seizure abortive properties. Yet, etomidate, one of the most commonly used RSI medications, has more conflicting (and low quality) data on its use in status epilepticus, especially as intubation is a fundamental step in the treatment of refractory status epilepticus. Thus, this study group wanted to investigate the association of etomidate on seizure cessation in RSE.

Methods

Design: Single-center, retrospective cohort study of a prospectively collected database of patients with suspected refractory status

Patient Population: Patients admitted to the neurocritical care unit between 2016-2023 for management of RSE, including convulsive and non-convulsive SE, and intubated in the hospital as part of RSE management. Intubations occurred in the ED, ward, or ICU.

Exclusion Criteria: If intubation occurred in the pre-hospital setting or at a different facility, intubation occurred after a single seizure not meeting RSE criteria, RSE was suspected to be due to hypoxic injury, or intubation occurred for an alternate indication.

Groups: Patients were divided into two groups, those intubated with anti-seizure agents (BZD, propofol, ketamine) (ASI) and those intubated with etomidate (EI). No recommendations regarding intubation agent were given and further management of SE was by institutional protocol.

Data Collection: Performed by chart review. Looked at patient demographics, clinical course, cEEG reports by attending epileptologists, and medication administration records. Otherwise chart abstraction is minimally described.

Outcomes

- Primary Outcome: detection of clinical or electrographic seizures in the 12 h following intubation. Selected to give ample time for EEG connection and monitoring.

- Secondary Outcomes: time to treatment failure, duration of anti-seizure infusion, time to recovery of command following based on a Glasgow coma scale motor score of six, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and peri-intubation complications.

- Exploratory sub-group analysis: patients already undergoing cEEG during the time of intubation to see if there was an immediate treatment response during induction.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the ASI and EI groups. Multiple logistic or linear regressions were used to examine the primary and secondary outcomes.

Results

Patients

- 697 patients were screened and 148 patients were ultimately included in the study cohort. The vast majority of patients were excluded due to intubation prior to arrival, either by EMS or at another facility.

- 90 patients intubated with ASI (57 propofol, 15 ketamine, 14 BZD, 4 Ketafol)

- The median dose of ASI agent was 1.19 mg/kg propofol, 1.44 mg/kg ketamine, 6 mg lorazepam, and 10 mg midazolam.

- 58 intubated with Etomidate

- ~0.29 mg/kg median dose

- 90 patients intubated with ASI (57 propofol, 15 ketamine, 14 BZD, 4 Ketafol)

- Baseline characteristics were mostly similar between groups, with no parameters reaching statistical significance.

- Of note, only 44.6% of patients were intubated after receiving both a BZD and an AED (or met the clinical definition of RSE), with a nonsignificant but notable difference between groups. 51.1% of the ASI group received both 1st and 2nd line agents while only 34.5% of the EI did.

- ~85% in both groups received rocuronium as their paralytic

- 98% underwent EEG monitoring, median time from intubation to monitoring of 4.2 hr, and if you exclude the patients already undergoing EEG, 5.1 hours

Outcomes

- No significant difference in clinical or EEG seizure occurrence in the 12 hours following induction (25% vs 29%)

- No significant difference in the rate of post-intubation seizures between groups.

- No significant difference on the duration of mechanical ventilation, time to recovery of command following, or duration of continuous anti-seizure medication infusion

Subgroup Analysis–EXPLORATORY

- 24 patients underwent intubation while on cEEG.

- 6 underwent etomidate induction, 18 underwent anti-seizure induction (majority propofol)

- 61% of the ASI group had cessation of seizures at time of intubation

- 0% of the etomidate group had cessation of seizures at time of intubation

- The median duration to resolve electrographic SE was 31.7 mins in the EI group vs 0 mins for the ASI group.

Safety

- No significant difference in post-intubation hypotension between groups

Limitations

- Single center, retrospective, small sample size

- Not an ED based study

- Chart review methods with limited description

- There was no control of SE management after intubation, which, if the monitoring period is 12 hours, leaves room for confounders, such as anti-seizure medication infusion selection and dosing.

- No controlling for the type of ASI chosen or when selecting ASI vs EI.

- This study also does not effectively comment on the choice of ASI and whether ketamine, benzodiazepines, or propofol would be the preferred agent. There was a non-significant signal in this study that ketamine and benzodiazepines performed better than propofol.

- Time to seizure monitoring with EEG ~5.1 hours after induction (seems consistent with real life but doesn’t say much about seizure cessation based on a choice of induction agent)

- ~85% of patients received rocuronium, which could mask clinical seizure activity that could be more informative of ASI or EI efficacy

Author’s Conclusion: In patients presenting to the hospital with SE who require endotracheal intubation, choice of induction agent for intubation is not associated with seizure cessation, duration of MV, or time to recover consciousness. However, in a subset of patients with EEG-proven SE at the time of intubation, induction using an anti-seizure induction agent during intubation may be beneficial in SE termination. Further prospective studies employing rapid-response EEG monitoring are needed.

Our Conclusions: This is a retrospective study that investigates the association of etomidate on seizure cessation in refractory status when compared to anti-epileptic medications for RSI. Although this study did not find a significant difference in seizure cessation when comparing ASI and EI for RSI, their exploratory analysis suggests that ASI may be beneficial in SE termination. Further study is needed given the limitations of this study.

Part 2: Status Epilepticus Management

In the second half of this podcast, Dr. Warr and Dr. Hine have a back and forth conversation about the best approach to treating the seizing patient in the ED.

As a primer, what’s our approach to the patient with status epilepticus? What should our initial considerations be for the patient in status?

Understanding the definition is critical to status epilepticus management.

We recommend following the guidelines set forth by the American Epilepsy Society and the Neurocritical Care Neurocritical Care Guidelines for Status Epilepticus published in 2012 and the most recent guidelines for the American Epilepsy Society published in 2016. The NCC guidelines define status epilepticus as 5 min or more of (i) continuous clinical and/or electrographic seizure activity or (ii) recurrent seizure activity without recovery (returning to baseline) between seizures.

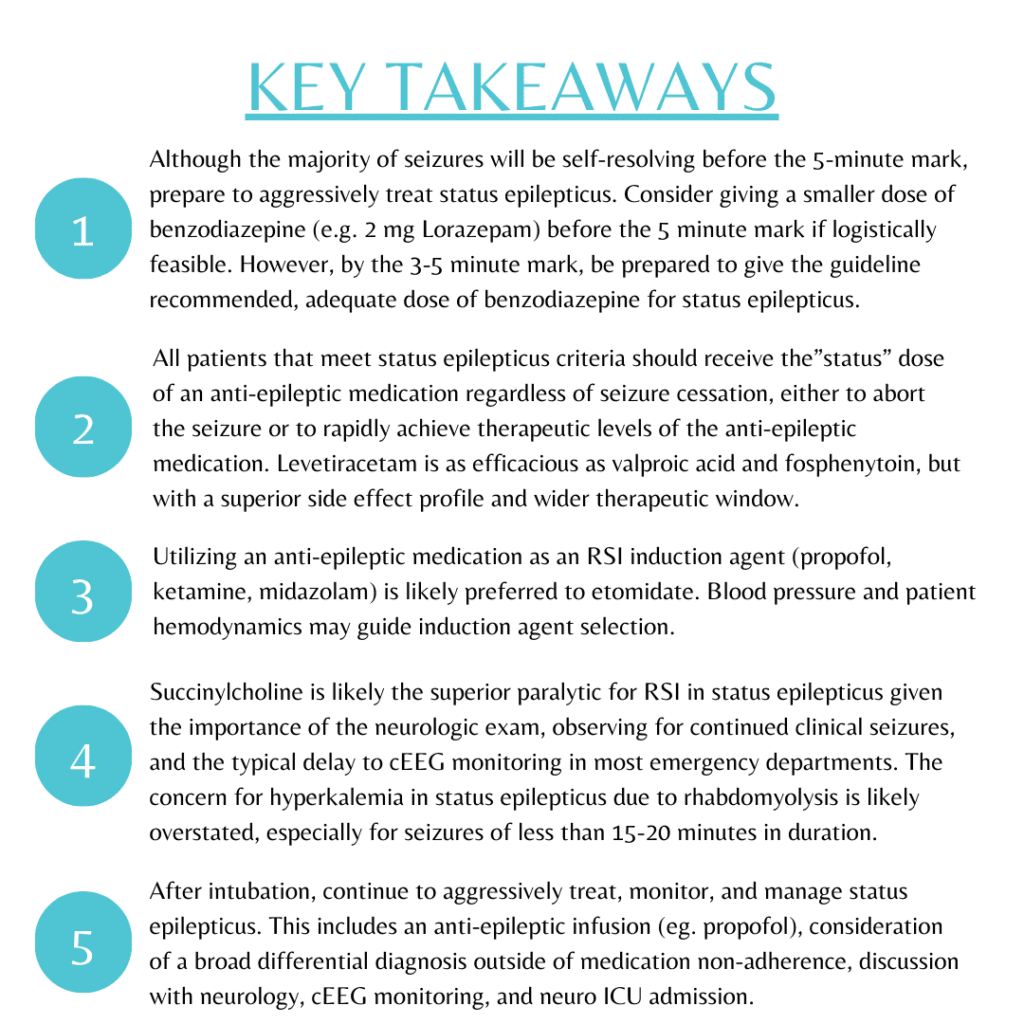

The pathway is clear once you hit 5 minutes or the patient is brought in by EMS actively seizing. It’s a bit more challenging to finesse those that start seizing in the Emergency Department. Most clinical and electrographic seizures end before the 5 minute mark. Those that extend beyond that are much less likely to stop spontaneously.

There’s an argument to be made that treatment of acute convulsive seizures less than 5-minute duration starts with supportive care, protecting the airway, and assisting breathing during the seizure and NOT reaching for benzodiazepines. Can call for your 1st dose benzo and give it at the 3-5 minute mark if the seizure does not stop spontaneously.

The challenge is that we do not know if it’s status epilepticus or a seizure that will stop spontaneously when it starts. You can consider giving IV Lorazepam 2mg or Midazolam 5mg IM immediately, and then calling for the guideline recommended dose of your first line medication to administer at the 5 minute mark if the seizure persists.

The sooner we recognize that the patient is in status epilepticus the better they will do. We need to be conscious that most seizures are short lived and will self terminate. That is why Jason approaches the first 5 minutes with a “lighter touch” than some might think when we already have your “status hat” on. Give the patient or the medications the meds time to work. However, the key is the plan for rapid dose escalation.

Logistically, it can take 3-5 minutes anyway for your nurse to pull midazolam or lorazepam and prepare it for administration. If the patient is still seizing, then it would be time anyway for medication administration. It is important to be explicit with your team about the plan for seizure management if you opt to wait until 3-5 min for medication administration, given the risk of undermining your leadership role as a resuscitationist (as the team by default often wants to give medications immediately when seizures start).

What about the patient who is seizing or recently seized who is brought in by EMS? Does your calculation change here?

Here we should embrace the immediate and aggressive treatment of status epilepticus. At this point, the patient at least meets the definition of Status Epilepticus according to the NCC. Address the ABCs, including POC glucose. If EMS has yet to give the first dose of benzodiazepine, here you should call for your 1st line (emergent) medication of choice depending on the presence IV access. Quickly escalate as needed to your 2nd line (urgent) and 3rd line (refractory) agents as needed.

Under-dosing of benzodiazepines is a common pitfall in the ED approach to status. How should we approach benzodiazepine dosing for status epilepticus?

Some guidelines recommend 4mg of lorazepam with a repeat dose if the seizure continues. Others recommend 0.1mg/kg IV (up to 8 mg) as an initial load.

Ultimately, it’s all about rapid escalation of management. Jason gives 2 mg lorazepam (or 5 mg of IM Midazolam) for seizures that start in the ED (as it aborts most). However, he is prepared to give the 4 mg of IV Lorazepam or 10 mg of Midazolam if the seizure continues beyond 5 minutes.

It is also important to consider the patient and their history. If the patient is larger, he may start with a 4 mg dose of Lorazepam in that initial <5 minutes phase and repeat the 4mg dose at the 5 minute mark. Alternatively, if a person has a known prior history of status epilepticus, Jason may escalate to status epilepticus dosing immediately. He has reservations of deleteriously affecting the disposition of an “easy out” patient with an 8mg IV Lorazepam initial dose.

Over-sedation of a patient that may quickly return to baseline could delay disposition. But we shouldn’t extrapolate that to respiratory depression. Evidence does NOT support the concept that benzodiazepines for status epilepticus promote respiratory depression and intubation. In fact, adequate doses of benzodiazepines may reduce the need for intubation. As the seizure progresses, studies have shown GABA receptors on neurons are internalized within cells. This reduces the sensitivity of neurons to benzodiazepines. Therefore, up-front adequate dosing of benzodiazepine provides the best chance for immediate lysis of the seizure. It’s a management tightrope that can be hard to balance.

Levitaracetam is becoming the favorite 2nd line agent after BZD, despite the evidence for valproate and fosphenytoin. Is there a reason to choose one of the other two medications at this point? Or is it Keppra all the way?

We use levitaracetam as our default agent. The ESETT (and in the pediatric world: EcLiPSE, ConSEPT) trial established equal efficacy of fosphenytoin, valproic acid, and levetiracetam. However, levetiracetam is increasingly being utilized as a front-line antiseizure medication. It is equally effective compared to other agents, yet it has a superior safety profile and is very easy to use. Why complicate things–same therapeutic effect but fewer adverse effects.

Guidelines actually recommend AED treatment following administration of short acting benzodiazepines in all patients who present with SE, unless the immediate cause of SE is known and definitively corrected. For patients who respond to emergent initial therapy and have complete resolution of SE, the goal is rapid attainment of therapeutic levels of an AED. For patients who fail emergent initial therapy, the goal of urgent control therapy is to stop SE.

When to start thinking about intubation in a patient with status?

Start thinking about intubation from the moment the patient begins seizing. Ultimately, there is no well defined period of observation that has been determined to be safe, and no data to suggest that watchful waiting is safer than proceeding with more aggressive treatment. We have to weigh the benefit of early seizure control vs. the risks of intubating a patient that may have avoided intubation.

Guidelines recommend intubation for continuous anti-seizure medication management in the case of refractory status epilepticus. This is defined as the continued clinical or electrographic seizure after receiving adequate doses of the initial benzodiazepine followed by the second acceptable antiepileptic drug (AED). We follow these guidelines and really try to save intubation for the patient who has not terminated their seizure after round 2 of benzodiazepines and AED (ie: Keppra) administration.

For the patient that does terminate, it’s okay to push the envelope some in the “airway protection” realm in these cases–poor mental state and concern for mildly compromised airway protection are not a reason to intubate the postictal patient, as they often have a relatively rapid improvement in mental status. Now, if the respiratory drive is really compromised then you are more likely to need to proceed with intubation. If the patient is not spontaneously ventilating after cessation of seizure, they must be intubated.

We proceed with intubation. What’s the approach? For our induction agent, are we reaching for propofol, ketamine, or versed? Or are we reaching for etomidate?

We prefer anti-epileptic agents over etomidate. Although there is weak evidence on their comparative efficacy, from a physiologic perspective, it makes sense to intubate using a medication that is known to cause seizure cessation. Although the study covered above did not find any statistically significant differences in the primary outcome, their exploratory subgroup of patients on cEEG during intubation did suggest superior seizure cessation when using an AED.

This is a time when the patient’s hemodynamics matter most. Blood pressure may well guide our choice of agent. If they are hypertensive, which many will be, propofol is the preferred agent. If they are hypotensive, then it may be best to use ketamine.

Etomidate, given its hemodynamic stability, could be useful in the setting of persistent seizures related to acute neurologic trauma as hypotension during induction would exacerbate secondary brain injury.

What about the choice for paralytic? Succinylcholine is a short acting agent that lets you observe clinical seizure activity but comes at the risk of hyperkalemia. Rocuronium doesn’t carry the theoretical risk of hyperkalemia, but could hide further seizure activity. How should the clinician weigh these options in the approach to the actively seizing patient? What do you think about attempting a no-paralytic approach to these patients?

Dr. Hine prefers succinylcholine. Although Dr. Warr and Dr. Hine are team rocuronium, status epilepticus is one major indication in our book to use succinylcholine. The neuro exam and identifying continued seizure activity is critical in these patients, especially given the delay to cEEG in most Emergency Departments. Unless they have known renal failure or another reason to fear their potassium, we are using succinylcholine. If the intubation is expected to be technically challenging, you can consider rocuronium, but then consider reversing them with Sugammadex.

Our concern here is seizure-induced rhabdomyolysis leading to hyperkalemia. Hyperkalemia secondary to rhabdomyolysis takes time to develop, so status epilepticus of short duration (<15-20 min) itself should really not be a contraindication to succinylcholine, in most patients. For a patient who presents to the ED with seizure of unknown duration, rocuronium is probably safer. However, based on multiple studies that included patients with normal renal function, succinylcholine leads to a serum potassium increase of roughly 0.5 mEq/L. This likely won’t cause a lethal hyperkalemic arrhythmia even in those patients with some degree of hyperkalemia.

The patient is intubated. What do we do now? What are our key management priorities and work-up besides getting this patient out of our ER to the Neuro ICU?

There is a tendency to high-five and walk away after any intubation. We need to avoid that urge. This patient needs sedation with an anti-seizure infusion. We favor propofol. Do not be afraid to give fluids or add a low dose of a vasopressor if the propofol infusion is contributing to hypotension. As intubation may have occurred beforehand, if the AED was not already given, make sure this has been administered.

This patient presented in extremis–and unless you know for sure this is all related to medication non-adherence, a broad differential must be considered and appropriately addressed. Unless we are confident it’s non-adherence, these patients will likely receive a CT Head. All should be put on cEEG as soon as logistically feasibly to evaluate for non-epileptic status.

Just remember the differential here: CNS infections, metabolic abnormalities (hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, inborn errors of metabolism, hepatic encephalopathy), stroke, trauma, drugs, drug withdrawal, hypoxia, and auto-immune disorders.

*Consider eclampsia in all reproductive age females

Read More About It:

Resources

- Woodward MR, Kardon A, Manners J, et al. Comparison of induction agents for rapid sequence intubation in refractory status epilepticus: A single-center retrospective analysis. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2024;25:100645. Published 2024 Jan 8. [pubmed]

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016;16(1):48-61. [pubmed]

- Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):3-23. [pubmed]

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, et al. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2103-2113. [pubmed]

- Lyttle MD, Rainford NEA, Gamble C, et al. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of paediatric convulsive status epilepticus (EcLiPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10186):2125-2134. [pubmed]

- Dalziel SR, Furyk J, Bonisch M, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of levetiracetam versus phenytoin for convulsive status epilepticus in children (protocol): Convulsive Status Epilepticus Paediatric Trial (ConSEPT) – a PREDICT study. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):152. Published [pubmed]