Piece of Cake: DKA/HHS Update Part I

Contributor: Dillon Warr, MD and Jason Hine, MD

Guest: George Willis, MD, FACEP

The American Diabetes Association released a consensus report in 2024 on the management of the hyperglycemic crises: DKA and HHS. Our goal is to give you some insight into the latest recommendations on the management of these critical presentations using this report as our guide.

In Part I, we discuss epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation of DKA/HHS. In Part II, we will discuss diagnosis and clinical management.

Keeping your skills up in rare procedures is an uphill battle. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting with simulation training that delivers to your door once a month. Use coupon code SimKit10 for 10% off

Key Points

1. Social determinants of health are key drivers of DKA and recurrent presentations. In this age of overpriced insulin, some patients are rationing their insulin use, giving enough to decrease their blood glucose, but unfortunately not enough to prevent ketosis. We need to ask our patients not only if they are using insulin, but if they are able to use it as prescribed.

2. Determine WHY the patient is in DKA. Think beyond insulin non-adherence, infarction, and infection and consider pregnancy and checkpoint inhibitors.

3. Etiologies of euglycemic DKA include insulin rationing, malnourishment leading to inadequate glycogen stores, pregnancy, and SGLT2 inhibitors.

4. If it looks like DKA, don’t be fooled by a normal or alkalotic pH. Look at their anion gap, check a beta-hydroxybutyrate, and trust your clinical exam. This could be diabetic ketoALKalosis

5. Sodium is NOT your friend in HHS. Beware a near normal sodium in the setting of severe hyperglycemia as the corrected sodium level will be much higher and it’s this sodium level that contributes to the mental status changes and increased mortality of this diagnosis.

6. If your pediatric patient with tachypnea or vomiting for a presumed URI or GI illness doesn’t respond to your treatment in a typical way, consider DKA.

State of DKA/HHS in 2025

Epidemiology

- There is a concerning rise in the rate of hyperglycemic emergencies in adults with both T1D and T2D in the last decade.

- Although those individuals with T1DM are more likely to present in DKA and those with T2DM are more likely to present in HHS, those with T1DM and T2DM can both experience HHS or DKA or even a combination of DKA/HHS.

- A substantial proportion of individuals hospitalized with DKA experience recurrent episodes. Every episode of DKA increases their overall long-term mortality.

- The rising cost of insulin is a key player in the increasing rates of DKA. Individuals are rationing insulin, giving enough to decrease their blood glucose, but unfortunately not enough to prevent ketosis.

Risk Factors and Precipitants of DKA/HHS

- DKA: infections, illnesses, infarction, injury, insufficient use of insulin therapy, infant (pregnancy), and inhibitors (SGLT2 inhibitors, checkpoint inhibitors).

- HHS: Infection (30-60%), surgery, infarction (stroke, MI), pancreatitis, and drugs (corticosteroids, sympathomimetic drugs, antipsychotics).

- There exists a bidirectional relationship between mental health conditions and hyperglycemic crisis

- The omission of insulin therapy, often in the setting of psychological and socioeconomic factors, is a major cause of DKA, particularly among adults with T1D living in socioeconomically deprived areas

- Multiple studies have suggested that low income, housing insecurity, and lack of insurance or presence of underinsurance lead to increased risk of DKA and HHS

Pathophysiology

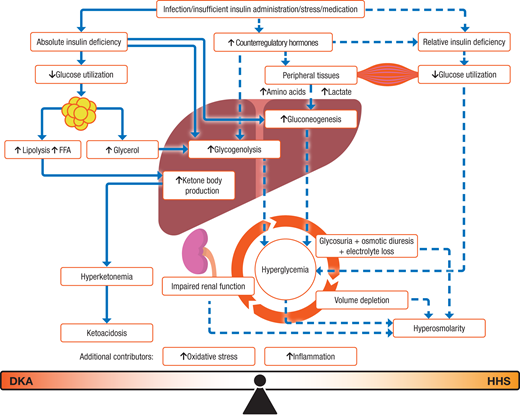

The key difference between DKA and HHS is the degree of insulin insufficiency.

DKA

“Classical” DKA

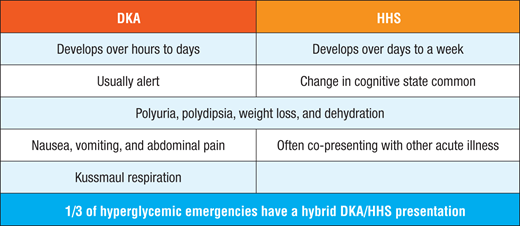

- DKA is characterized by severe insulin deficiency and a rise in concentrations of counterregulatory hormones, leading to increased gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and impaired glucose utilization by peripheral tissues.

- The combination of insulin deficiency and increased counterregulatory hormones results in the release of free fatty acids from adipose tissues and subsequent fatty acid acid oxidation and the resulting production of excess ketone bodies with resulting ketonemia and metabolic acidosis.

Euglycemic DKA

- Euglycemic DKA can be caused by a variety of factors, including exogenous insulin injection, reduced food intake, pregnancy, or impaired gluconeogenesis due to alcohol use, liver failure, and/or SGLT2 inhibitor therapy.

- The underlying mechanism of euglycemic DKA is secondary to a carbohydrate deficit with simultaneously elevated counter regulatory hormones. It’s this increased glucagon/insulin ratio that leads to ketogenesis in the absence of significant hepatic gluconeogenesis or glycogenolysis.

Diabetic Ketoalkalosis

- Patients with DKA can have mixed-acid base disorders as a direct result of their underlying metabolic acidosis. They can develop primary metabolic alkalosis from volume contraction or from persistent emesis of acidic stomach contents or primary respiratory alkalosis from Kussmaul breathing.

- Patients can therefore present with hyperglycemia, positive serum ketones, and increased anion gap metabolic acidosis, but with pH > 7.3 or bicarbonate > 18 mmol/L. Patients can even present with alkalemia with pH > 7.4, which is termed diabetic ketoalkalosis

- Use the patients anion gap and beta-hydroxybutyerate level to facilitate a diagnosis, in addition to your clinical exam. Don’t be fooled by a pH.

HHS

- Less severe insulin deficiency and therefore sufficient insulin to prevent ketogenesis but not enough to prevent hyperglycemia.

- Hyperglycemia leads to an osmotic diuresis, leading to volume depletion and hemoconcentration.

- Sodium is a major, often underlooked player in this condition. It’s the sodium that is the biggest driver of osmolarity and the patient’s altered mental status.

- A normal sodium level in the setting of severe hyperglycemia is concerning and suggests severe hypernatremia.

Presentation

- It is important to consider the differential diagnosis of elevated ketones, including starvation ketosis, alcoholic ketoacidosis, and ketosis of pregnancy and hyperemesis

- Patients should be examined for signs of infection, ischemia, and other potential precipitants of a hyperglycemic crisis.

Pediatric Pearls

When to consider DKA and get that fingerstick:

- Tachycardia in kids with GI illness or URI symptoms that continues despite antipyretics, even in those patients with “low-grade fevers”.

- Persistent tachypnea with clear breath sounds despite nasal suctioning and nebulization.

- Disinterest in food despite cessation of vomiting with antiemetic administration.

References

Umpierrez GE, Davis GM, ElSayed NA, et al. Hyperglycaemic crises in adults with diabetes: a consensus report. Diabetologia. 2024;67(8):1455-1479. [pubmed]

Cao S, Cao S. Diabetic Ketoalkalosis: A Common Yet Easily Overlooked Alkalemic Variant of Diabetic Ketoacidosis Associated with Mixed Acid-Base Disorders. J Emerg Med. 2023;64(3):282-288. [pubmed]

One Response