Contributor: Jason Hine, MD

Recognition of serious bacterial infections in young children is a challenging clinical dilemma. there have been several decision rules and algorithms for working up these potentially sick neonates. one question that has come up is the utility of specific tests Within These algorithms with early presentation to the emergency department. data is suggesting that febrile neonates are presenting to the emergency department more rapidly and earlier in their disease process likely related to increased awareness of the potential serious causes for this and increased ability to access care.

Practicing procedures can be tough. Let SimKit do all the heavy lifting in your skill maintenance. Procedural training can and should be easy, done in your home or department, and work within your schedule. Get 10% off with coupon code SimKit10.

The Paper

Performance of Febrile Infant Algorithms by Duration of Fever. By Gomez Velasco et al in Annals of Emergency Medicine May 2024.

Velasco R, Gomez B, Labiano I, Mier A, Ugedo A, Benito J, Mintegi S. Performance of Febrile Infant Algorithms by Duration of Fever. Pediatrics. 2024 May 1;153(5):e2023064342. [pubmed]

The Clinical Question

In this article in Pediatrics from May 2024, the author’s attempted to evaluate different inflammatory markers and their incorporation into decision AIDS for February neonates presenting at various time points from the onset of fever. They were looking for invasive bacterial infections (IBIs)- notably bacteremia or bacterial meningitis.

The Structure

This was a secondary analysis of a prospective single center registry data set. They collected information on all consecutive infants who were less than 90 days old with a fever- who did not have a source. All of these sick kids were presenting to a single pediatric emergency department between the years 2008 and 2021.

They broke the duration of fever down into three categories:

– < 2 hours

– 2 to 12 hours

– > 12 hours

With the data collected on these children, they looked at the performance of different biomarkers as well as three algorithms for working up these febrile neonates the PECARN, AAP, and Step by Step clinical decision rules.

They had a total of almost 3000 <90 day old kids in the registry. After exclusions they ended up with 2,565 children, giving an exclusion rate of 14%.

Inclusion Criteria

-Kids were considered for inclusion in the study if they presented to the research hospital again between the years 2008 and 2021, were less than 90 days old, and were presenting with a fever without a source.

-Importantly, they did not exclude kids if they were ill appearing, which many of the decision aids do.

Exclusion Criteria

They were excluded if:

-there was data lacking on the duration of fever

-none of the studied biomarkers were obtained (WBC, ANC a CRP, and a procalcitonin)

-blood cultures were not obtained

Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to look at how these biomarkers and clinical decision rules perform in diagnosing IBI or invasive bacterial infection and here were referencing bacteremia or Bacterial meningitis.

Results

Looking at the patient population, we have about 2,500 kids. The average age was 52 days. About 2.5% of them were actually not well appearing which comes into play when analyzing our decision aids- which usually require a well child. They found that about 25% had a fever duration less than 2 hours. About 48% were 2 to 12 hours and about 28% greater than 12 hours.

Interestingly, we note that during the study period the rate of infants presenting within that first two-hour period increased significantly. It was 17% in the first study year of 2008 and 30% by 2021. That is worth taking time to digest- we are probably going to be seeing more kids early on in their disease process given this trend and likely related to awareness and ease of access.

Biomarkers

We will start by looking at the greater than 12 hour group. This is kind of looking at how these biomarkers preform under ideal circumstances. We expect there to be some degree of lag in the biomarker elevation from the onset of fever or the inflammatory process.

Now these numbers are delivered as area under the curves or AUC. As a refresher, it is generally thought that a 0.7 or higher is acceptable, 0.8 or higher is pretty darn good and 0.9 or higher is excellent.

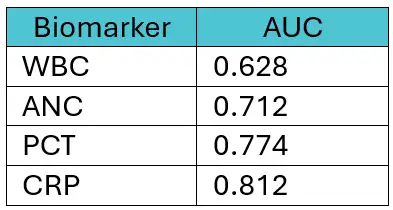

>12 Hour of fever

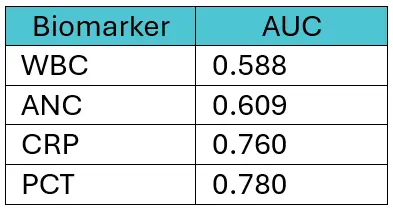

2-12 hours of fever

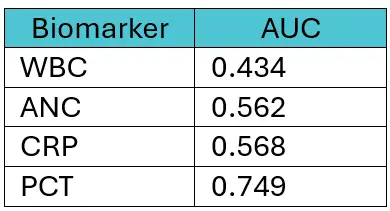

<2 hours of fever

In looking at these numbers, we see (somewhat as expected) that the biomarkers do better when the inflammatory process has been well established- ie in the >12 hours since fever onset group. Interestingly, here CRP outperforms procalcitonin by a bit.

In the 2-12 hour group, we see both CRP and procalcitonin both maintain themselves above that 0.7 AUC we look for.

In the <2 hour group, three of the four biomarkers are well below that 0.7 cutpoint, with only procalcitonin having an acceptable AUC.

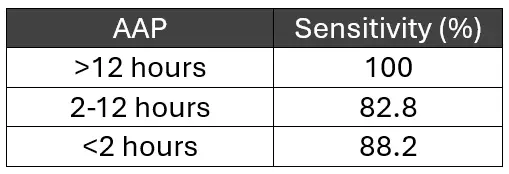

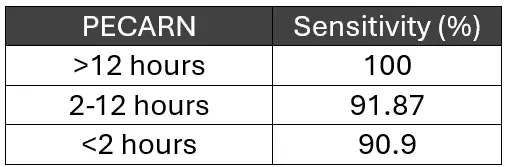

Decision Rules

For our assessment of decision rules, we are going to focus on the sensitivity because, again, we want to this to be sensitive- we want to find these kids who are at risk or going to have IBIs. We don’t want specificities in the floor but, spoiler alert, they were all between 44 and 54% specific.

It is worth noting that for these rules they only included children within the specified age ranges for them- PECARN for example 29 to 60 days and AAP 8 to 60 days of life.

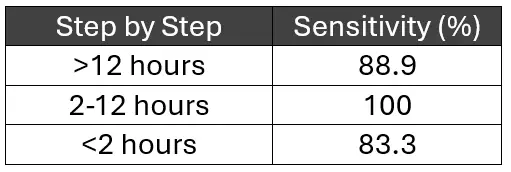

Step by Step

AAP

PECARN

So as we can see, not great preformance of these clinical decision rules across the board. Each one has its own area where it gets to 100% sensitive, which we will talk about below. But when not 100%, the numbers are not very impressive. The best is PECARN 2-12 hours, at 92%, meaning the rule would would miss 1 in 12.5 kids with IBIs.

Discussion

In their discussion, the authors’ point out the trend toward earlier presentation for neonatal fever. They also note that the younger the patient is, which also for us often makes us more and more worried about serious bacterial infections or invasive bacterial infections, the more likely the child was to present earlier or less than 2 hours. Great,

Interestingly, they also noted a difference in the pathogen for the different groups depending on how early they presented. With shorter duration of fever, there’s a higher likelihood for streptococcus agalactiae. Whereas E coli rises to be the most common bacteria isolated in these pediatric patients when fever was greater than 2 hours duration.

What to do with this data?

The first thing to address is the sensitivities and specificities for the decision rules that we often use in clinical practice. It is very interesting to note that PECARN and AAP both had their 100% sensitivity in the greater than 12 hour duration of fever group. Step by Step, on the other hand, had its 100% sensitivity in the 2 to 12 hour range. Attempting to explain this, the authors of this paper note that in the original derivation studies, the average length of fever was different for each of these decision aids. The Step by Step sample had a median of 5 hours of fever which may be explains the 100% sensitivity in that 2 to 12-hour range. Whereas in PECARN they note that almost 40% of their patients had fever for more than 12 hours.

It is dicey and probably ill advised to use different clinical decision aids in these groups depending on how long the fever is ongoing, and not really practical as many of our pediatricians in our hospitals speak one language, whichever decision aid or rule that hospital system has chosen. Certainly, being aware of the limitations of these different Clinical decision rules is important. And unless you’re involved in the Committees involved in in corporation of these decision rules into hospital practice, that’s the most we can take from this data.

Regarding the paper’s major purpose of assessing the efficacy of biomarkers in children with very short duration of fever, particularly less than 2 hours, we have to recognize the limitations as outlined by this paper. When we come back to that Figure 1 and the Area Under the receiver operator Curve (AUC), we see only procalcitonin being above that 0.7 cut point of acceptable with the number of 0.749. This is of course problematic because many hospitals don’t have access to a early or rapid procalcitonin.

Solutions to the Problem

The author’s offer 3potential Solutions this problem:

Solution 1

The first is to draw the laboratory work as you normally would in work out these patients and repeat these biomarkers after a few hours. a notable limitation for this is the more often a lab test is drawn the higher the probability for a false positive result.

Solution 2

The second option is to initiate therapy as you would right away for these febrile neonates and wait a few hours to perform the first Laboratory analysis, which would again give time for the biomarkers to reach their maximum performance.

Solution 3

The third solution, which of course we all will agree with, is that There should be future production of specific clinical decision rules in patients with a shorter duration of fever.

Within these first two solutions, I would lean toward the first with a repeat laboratory work if the initial screening is putting a patient in a low-risk categorization. This is of course particularly true if you have procalcitonin. If you don’t and complete the work up immediately as we should for these febrile neonates/infants and initiate appropriate therapy, and the initial work up puts the patient in a low-risk categorization, we should certainly consider repeating these labs after a few hours.

We recognize and agree with the increased probability for a false positive result in these patients, but remember we are looking for sensitivity in these kids not specificity, and being overly cautious largely has been the name of the game. Now if your pediatric groups support initiating therapy so as to not delay treatment of the child and then waiting a few hours for laboratory extraction, I think that also is a viable option. Both of course need buy-in from our pediatric colleagues who will be receiving these patients if admitted.

Authors' Conclusions

In this article the authors conclude that “management of the febrile young infants with a very short duration of fever should be more cautious. the performance of blood biomarkers except for procalcitonin in febrile infants decreases in these infants, and this may alter the performance of different clinical decision rules.”

Our Conclusions

From this article, we see that the clinical decision aids of Step-by-Step, PECARN, and AAP have different performance characteristics depending on the duration of fever, and all perform somewhat poorly for patients with less than 2 hours of fever. We should be conscious of these limitations of the clinical decision rule utilized by our hospital or hospital system.

Related to biomarkers, we recognize that it takes time for these laboratories to become elevated or abnormal, which can lead to erroneous reassurance when assessing them early on, particularly less than 2 hours from onset of fever. This is true for all biomarkers, all of which had lower performance in the area under the curve analysis, but procalcitonin maintained an acceptable AUC of 0.749 even in the <2 hr of fever group.

If using a biomarker other than procalcitonin, consider drawing these inflammatory markers after the patient has initiated therapy or redrawing them a few hours into the Emergency Department stay- of course in consultation with your Pediatricians.

References

-

Velasco R, Gomez B, Labiano I, Mier A, Ugedo A, Benito J, Mintegi S. Performance of Febrile Infant Algorithms by Duration of Fever. Pediatrics. 2024 May 1;153(5):e2023064342. doi: 10.1542/peds.2023-064342. PMID: 38563061. [pubmed]