Alcohol use disorder and withdrawal in the Emergency Department is as commonplace as a turkey sandwich. Despite this, there is wide variation on how we categorize and treat withdrawal. In this podcast, we organize withdrawal symptoms and structuralize an approach to the withdrawing patient.

Jason Hine: Hello everybody and welcome to our podcast today on alcohol withdrawal. Now this might be one of, if not the most ubiquitous diagnosis that we see in the emergency department. Alcohol intoxication, patients coming in with alcohol use disorder or getting admitted to having alcohol withdrawal. This is an incredibly common condition for us in the emergency department. One thing I have recognized though, particularly working with learners, there is, there’s a lot of confusion or variability in the way that these patients are managed. This in part has to do with a general lack of well founded evidence for benefit of one agent over the other, how people practice in variations and practice patterns. And this makes treating these patients systematically and consistently, relatively challenging. But alcohol withdrawal is obviously incredibly common. It’s actually estimated that about half a million people in the United States get pharmacotherapy for symptoms of withdrawal every year.

To understand this, let’s talk a little bit about what alcohol does to the brain so we can understand withdrawal state pretty well. So first, we’re going to do a brief and high level pathophysiology. We’ll go through this quickly. We’ll try to keep it interesting. Ethanol or alcohol, it is a neuro depressant. In our brains, there are two major receptors that we need to consider here, GABA and glutamate. Now you can think of GABA as the break and glutamate as a gas. Now I remember when I first learned or was learning how to drive a car I got in the driver’s seat and I put my right foot on the gas and my left foot on the brake. I quickly learned that that is weirdly not how we do it. That’s not how we drive. We have a single foot, we press the gas, we press the brake. In the brain, these neuroreceptors are being hit at varying levels and varying degrees all the time. We all have a set number of GABA and glutamate receptors. Now as a neuro suppressant, when the brain is exposed to very high levels of alcohol chronically, we recognize the body does not want your life to pass by with you in a coma. So the body or brain will up regulate glutamate, the gas, and downregulate GABA, the brake, to allow the chronic alcohol use disorder patient to be alive, to be walky and talky, with higher and higher levels of blood alcohol. Levels that are well above what would put us into a coma or put us in a terrible state. We see these patients walking around, interacting at incredibly high levels because of the down regulation of GABA and the upregulation of glutamate.

So now in the withdrawal state, when alcohol is removed, we do not have enough of the GABA and we have unopposed or under opposed glutamate. Now we can understand why the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal make sense. We are going to see autonomic hyperexcitable, tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, tremors, hallucinations, seizures, and the severity of withdrawal is going to depend on the canonicity of the person’s alcohol use and how much drinks they have per day or per sitting. And if they’ve had any times of abstinence in between, these are times when the brain receptors are going to start regulating back toward normal. It’s also thought that genetics may play a possible role. So now that we have an idea of what alcohol does to the brain, what the neuroreceptors are doing, what the withdrawal state might look like, we’re going to talk about the stages of withdrawal.

But before we do, we should really get into some concurrents, because to talk about alcohol withdrawal isolation is a folly and an opportunity to miss another important diagnosis. We’re going to briefly discuss concurrent conditions and sort of get that out of the way. The withdrawing alcoholic has a potential for many concurrent diseases that can confound the treatment or the presentation, and they themselves need treatment. So, the first one is dehydration. Alcohol itself has a direct diuretic effect and will often replace water as the oral liquid of choice. So if the patient is vomiting, that is obviously going to increase that volume depletion, but patients in withdrawal are often relatively volume down. Now, hypoglycemia, with poor nutrition replacing much of their caloric intake with alcohol and having low glycogen stores: chronic alcohol users are at risk for hypoglycemia. Low thiamine: now this is a classic deficiency thought to be nutritional and we all know that this precipitates Wernickes Encephalopathy. Hypomagnesemia: now the etiology of this is similar to kind of the above talk about dehydration. We got diaphoresis and nutritional deficiencies. Some research out of Canada has shown that it’s one of the most common causes of hypomagnesemia. But others had questioned this validity. The point being that a hypomagnesemia state may be present in your chronic alcoholic. And of course, there are the other things that come with alcohol use disorder. They can include psychiatric illness, trauma, among others. So let us not forget these concurrents or other diagnosis that may confound the presentation of the patient coming in with alcohol withdrawal.

All right, let’s talk about the stages. Here we’re going to talk about timing. The first symptoms of withdrawal typically occur within the first 6 to 12 hours from their last drink. And as we said, these are well known to us. They’re the autonomic excitation that we mentioned earlier. Now, some will describe this as stage one of withdrawal. This again, is going to be tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, there is common, tremors, these are the typical early manifestations of withdrawl state. Now on to stage two, the next stage. This is in the 12 to 48 hour range since last ingestion. Now, some people may not progress past the above stage one and symptoms will be uncomfortable. They will gradually abate. Again, this is going to depend on how long they’ve been drinking and at what quantity. But in discussing the natural progression toward alcohol withdrawl delirium, colloquially called delirium tremens, we often see an escalation toward this second stage. In the 12 to 48 hour range, we can see movement toward hallucinations. This is often included in seeing or feeling things like bugs on the skin called formication. This confused state does share some characteristics with alcohol withdrawal, delirium or delirium tremens, but timing is very important here. As we mentioned, this is in that sort of 12 to 48 hour range and very importantly, the baseline mentation is important. These hallucinations are usually without a loss of sense of reality. They can be found to be distressing by the patient who is still at grips with reality and recognize that these are hallucinations and they often occur in that sort of 12 to 24 hour range and usually resolve before 48 hours. The other important manifestation in that sort of second stage, stage two, is the alcohol withdrawal seizure. This often occurs after 24 hours from the last drink. Now early in my career I saw this as a major red flag, a high probability of progression to alcohol withdrawal, delirium, needing emission, et cetera. In reality, alcohol withdrawal seizures can represent a patient population at risk for alcohol withdrawal delirium, but with adequate and aggressive therapy, it is not necessarily poor tender, poor prognosis. They seem to be more common in drinkers who are in their 40s or 50s, likely related to prolonged and sustained alcohol use, so that definitely needs to be respected. Now the first part is next sentence is the most important. If left untreated, it is estimated about one in three patients with alcohol withdrawal, seizures will progress to alcohol withdrawal delirium. By treating these patients adequately and aggressively, this does not necessarily portend a poor prognosis or progression to delirium tremens. Now the alcohol withdrawal seizure itself is usually a self limited single seizure or a handful of seizures in a short period of time. Status epilepticus should definitely prompt aggressive treatment and should not be attributed to the alcohol withdrawal seizures. This is time to go hunting for those other things that people with alcohol use disorder can have: trauma, infections, electrolyte disturbances. You name it. Now the final stage is Stage 3 and it’s again most appropriately called alcohol withdrawal delirium, but is commonly termed delirium tremens, or DTs. The earliest you are going to diagnose this is 48 hours from the last drink, but the window is actually up to four days. The typical time for alcohol withdrawal delirium is 48 to 72 hours. Now, in addition to the above mentioned autonomic excitation of tachycardia, diaphoresis, tremors, vomiting, which is at this point typically quite profound, patients will have an altered sensorium, hallucinations, and agitation. Interestingly, the ICD 10 code for delirium tremens is really just a combination of the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal and delirium. To look at those specifically the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal by the ICD 10 are tremors of the tongue, eyelids, arms, sweating, nausea, retching or vomiting, tachycardia or hypertension, psychomotor hyperactivity, headache, insomnia, malaise, or weakness, transitory visual, auditory, or tactile hallucinations and seizures. For the signs or symptoms of delirium, they state it is a clouding of consciousness, reduced clarity of awareness or reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention, disturbance of cognition, psychomotor disturbances, disturbances of sleep and sleep/ awake cycle, and a rapid onset and fluctuation of symptoms over the course of the day. As you can see, it’s essentially the combination of an alcohol withdrawal state and the presence of delirium. In reality, this diagnosis is usually made with a history of alcohol cessation timeframe that matches the diagnosis, 2 to 3 days. It’s provided by family, EMS noting vomiting with no oral intake for three days and a sick as stink patient with autonomic hyper excitation.

Now, briefly, the risks for progressing toward alcohol withdrawal delirium include the time since the last drink. Obviously, timing is important. The quantity of alcohol consumed on average, the length of time since their last sober period, so that resetting of our neuroreceptors, prior episodes of withdrawal and their progression. That’s called the kindling effect. And as we mentioned, a history of seizures and untreated withdrawal.

Alright, now that we have an understanding of the progression through alcohol withdrawal, let’s talk about sort of scoring staging and treating these patients. One of the most common ways to objectify the subjective of alcohol withdrawal is with the CIWA score. This is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment and most of us are using the alcohol scale revised version of it. In this scoring system, there are 10 categories with a max score of 67. Now, while we mentioned this is a way of objectifying these objective, recognize that within this score there are only a handful of objective measures and several subjective ones. The objective ones are generally considered tremor, sweats and agitation, with the other seven being subjective, including things like sensation of anxiety. So while this score is useful, it is very important when you have someone that, say, gets a score higher than expected or when evaluating the score itself to look at the areas where the patient scoring. Concurrent psychiatric illness can sometimes artificially elevate this, but collectively this is a great way to try to objectify something that’s relatively subjective. So how does the scoring breakdown? There are several ways that people will break down a CIWA score into different buckets. Some will do a 0-8, 9-15, 16- 20 and greater than 20. I personally like to simplify this and make memorization a little easier, just using 8 and 16. Less than 8 is mild. 9 to 15 is moderate. And greater than 16 is severe. And the other very important part about the CIWA score is that it can be used longitudinally in a single patient. So recognizing their score and presentation and rescoring them often every hour or two hours to see what direction they are going is incredibly valuable.

OK. So with that in mind, let’s talk about treatment. We’ve recognized a patient with alcohol withdrawal. We are scoring them probably with this CIWA score and now we’re ready to treat them. Again, a quick plug to recognize and manage the concurrent diseases. Do not forget about those1 As a reminder, as we get ready to treat this patient, we need to consider a few things: the severity and chronicity of their alcohol abuse, the time since they stopped concurrent use of other sedative hypnotics, the patients age, concurrent diseases, and history of prior withdrawals. All of these have been shown to increase the chance of the patient going on to alcohol withdrawal delirium and recognition of them, particularly an accumulative quantity of them is going to inform the level of aggressiveness we use in treating these patients.

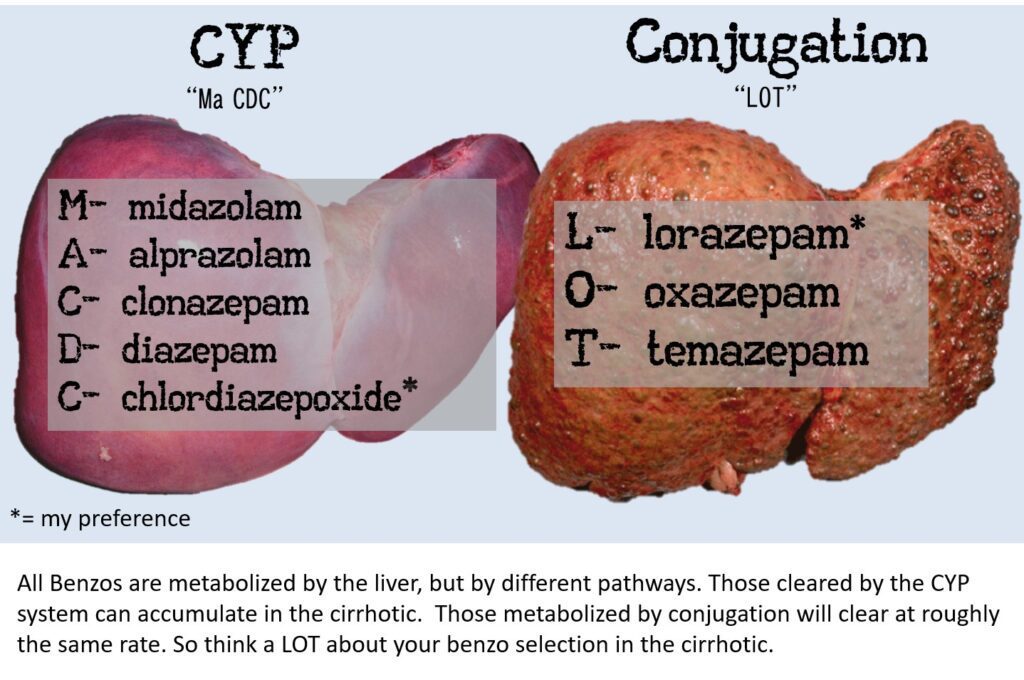

So let’s talk about them in these three camps that I typically break them down, the mild symptoms, low risk history, this is the CIWA score of 0 to 8. It is important here to recognize that many patients may not require active pharmacologic therapy. Patients without a heavy alcohol use history who don’t have any of the red flags noted above, who have minimal symptoms. Again, scoring on a CIWA score of less than or equal to 8, may not require any medications at all. Now we will talk a little bit at the end about naltrexone, something to consider and then you’re going to have to read the room a little bit, some supportive therapy to help them even with their mild symptoms may be beneficial. Alright, the moderate risk history or the moderate symptoms, the CIWA score of 8 to 15. This is kind of the ideal ambulatory treatment patient. If all the right boxes are checked; they have moderate symptomatology, they fall in that CIWA score range of 8 to 15, they can be considered for outpatient pharmacological therapy. The things that we need to recognize is that they can take oral medications, they have reasonable self-care, they’re not psychotic, suicidal, cognitively impaired. Ideally, they have a good social support for the withdrawal itself and then the treatment process collectively. And now we got to talk about agents. The ideal agents in treating withdrawal is going to be one that allows the GABA glutamate imbalance in the brain to kind of gradually return to normal and mitigate these hyper excitation symptoms. Really what we’re talking about here are benzos, benzos, benzos, benzodiazepines. Quickly we should mention other neuroleptics and comparisons of benzodiazepines to these other neuroleptics. They’ve been shown to be inferior to benzodiazepines, actually with a relative risk of death of 6.6. So we are using benzodiazepines and we’ll talk about phenobarbital and propofol later as the mainstay of therapy. Now the ideal benzodiazepine is a topic of hot, hot debate. Meta analysis have not shown one agent to be superior to the other, but several have been considered: diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, and chlordiazepoxide. Essentially, there’s kind of two schools of thought that seem to come in considering your favorite agent. One school is kind of the use of a long acting agent like diazepam or chlordiazepoxide, which has a smooth natural taper, given its half life and again with active metabolites. The downside here is that they have a different conjugation than the second option. The sort of shorter acting, but “cleaner” agents like lorazepam, which do not have as many concerns in patients that have impaired liver metabolism. All benzodiazepines are metabolized by the liver. There are two different ways that that is done. There’s a CYP system as well as conjugation. In patients with cirrhosis, the conjugation system is generally maintained, so metabolism will be typical. The most commonly used agent that is metabolized by conjugation is lorazepam, so this may be a preferred agent in this … I personally like chlordiazepoxide for my outpatient care. This is Librium; it is a slow up, slow down. It has active metabolites. It is not a commonly abused agent like Lorazepam or Ativan, which has a more rapid onset of action and can certainly induce some euphoria. We are all familiar with that. Many, many opinions exist on this and the providers comfort and the patient’s oral status is going to matter. Lorazepam or Ativan and diazepam or Valium have IV versions where chlordiazepoxide or Librium does not. Now with that in mind, the patient that has all the right boxes checked for potential outpatient taper can be considered to start with an IV dose, especially if they have intolerance to oral or vomiting significantly and can then be transitioned to their oral dosing medication. The next question is how much of this medicine to give. An approach that I have liked and adopted is to sort of tally the total ED dose required to cause symptomatic improvement and relief, decreasing in improving CIWA score and then created taper from that in the following manner. Day one, you take the total ED dose of the medication and you divide it out four times. Day two you take 1/3 of that dose, divide it out four times, day three 1/2 day, four 1/4 and day five, you transition off. Depending on the patient and your comfort with this, I will sometimes extend these dosing’s out further, recognizing that a four day taper may not be a long enough treatment timeframe. Now, by this point, the patient may be with an outpatient provider or a detoxification center, but I will often extend this out further to a roughly 8 day supply, giving a two day supply at each time frame. So day one and two, they get the total dose, divide out four times a day, day two and three 3/4 of the ED dose, day four and five one, one half etc. Now, it’s also incredibly important to recognize that our management of the withdrawal state is only part or half, or probably less than half of this person’s battle to gain sobriety. The psychosocial supports necessary to maintain abstinence are as important or probably more important than the management of the physiologic withdrawal. Alright, let’s move on to the severe risk history or the severe symptoms that CIWA score of 16 or greater or some people say 20 or greater. These patients that look bad, are scary, and you have a high concern for alcohol withdrawal delirium or progression toward it. Now, treating this can be a podcast in and of itself, but luckily alcohol withdrawal delirium is relatively rare. It is estimated to be seen in roughly 5% of patients who are actually admitted for the management of withdrawal. Mortality rates for alcohol withdrawal delirium used to be as high as 15%, but with the recognition of our cells needing to be aggressive in the treatment of this and avoiding our fear of high dose benzodiazepines and other agents with current treatment regimens, the number is closer actually to 1%. Now for treatment, benzodiazepines have been the mainstay and are probably the agent of choice for many of us. Patients with alcohol withdrawal delirium require aggressive and frequent doses of benzodiazepines. These are usually by IV administration. The dose is unique to the individual and their tolerance, but the overall goal is the same: we want light sedation. Now, again, no one benzodiazepine has been proven to be better than any of the others. But given that alcohol withdrawl delirium requires rapidly escalating doses or often drips, consideration of the duration of action and the active metabolites comes into play. Agents with good pharmacological profiles include Diazepam Valium, Lorazepam Ativan, and Midazolam Versed . Now generally many will prefer diazepam here or other long acting agents that have active metabolites because of the smoother transition to oral or to tapering. But one should also consider shorter acting agents and ones that are metabolized by conjugation in the liver, like lorazepam in patients with severe agitation, hemodynamic compromise and patients with cirrhosis. This helps prevent sort of the over sedation that you might see down the road. Now it’s important to state here that we are using doses of benzodiazepines, not like we use in every other type of patient. Nursing comfort and conversation with them about the dosing that you are choosing, the recognition of very high dose benzodiazepines and the reason for their need can help mitigate some of the fear of administration, seen by your nursing staff. Now when you know when you’ve given enough, the answer again is not really in milligrams, but in examination. Quietly sedated but rousable, really is the goal. To put this in a quantitative measurement, you want a RASS of 0 or -1. In some patients, benzodiazepines simply won’t be enough, either you’re going to exhaust your supply or your seasoned nurse is going to just say, I don’t think this is safe any longer. Adjunctive treatments may be necessary to achieve that RASS of 0. The ones with the greatest amount of literature to support them are phenobarbital and propofol. Dosing of these agents will clearly depend on the amount of benzos you’ve given and the patients dynamics currently, but with the dual sedative hypnotic agents, preparation for airway vehicle is a must.

Dosing for phenobarbital in the alcohol withdrawal patient are mentioned here in the show notes. Now, as we mentioned, we wanted to talk at the end about Naltrexone. This is an agent that is not going to be managing the GABA glutamate imbalance in the patient. But in those mild to moderate 0 to 8 patients or in the patients that have moderate withdrawal that are stabilized and safe for an outpatient taper. These are ones to consider naltrexone. Interestingly, naltrexone has been found to decrease cravings in patients who are going through alcohol withdrawal moving toward sobriety. The dosing here is 50 milligrams once daily and after a week you can increase that dose to 100 milligrams depending on the patient’s response or how well they’ve tolerated the medication. As we mentioned, getting the patient through their acute withdrawal, managing their signs and symptoms of withdrawal is only part of the battle. I’d say less than half. Getting the patient to gain full and maintain sobriety is incredibly important. Now hopefully you can be doing this in conjunction with the detoxification center, but we’ve seen those patients who have had that Librium taper, 5 times that year. We need to recognize that we are doing wrong by these patients if they are contemplated and eager to gain sobriety, but we are not working on the psychosocial element, the craving element, and the need for support in the long term through a sobriety program or detoxification center.

All right, let’s do a quick summary before we wrap up. Alcohol withdrawal is an incredibly common condition, and we see about 1/2 a million people in the US getting pharmacotherapy for this every year. The pathophysiology of alcohol withdrawal includes GABA and glutamate, the break and the gas respectively. When the brain is bathed in alcohol chronically, you will naturally down regulate your GABA and upregulate your glutamate, so you can be awake with higher levels of alcohol. When that alcohol is removed, there is too much gas, not enough break, so the patient will present with autonomic hyper excitation, tachycardia, hypertension, tremors, diaphoresis, hallucinations, seizures and alcohol withdrawal delirium. We mentioned briefly the concurrents that we need to think about and recognize in the right clinical case. And then we dove into this sort of stages of withdrawal. The first stage is seen in those first 6 to 12 hours. Patients will have that autonomic hyper excitation. The second stage is seen in sort of that 12 to 48 hour range and this is highlighted by the hallucinations, formication as well as the alcohol withdrawal seizure. While untreated, alcohol withdrawal seizures can increase the probability of going on to alcohol withdrawal delirium, about 1/3 of patients will. Recognize that an isolated, alcohol withdrawal seizure in and of itself does not commit a person to inpatient stay, nor does it portend a bad prognosis. The final stage or stage 3 is the alcohol withdrawal delirium. It can occur as early as 48 hours after last drink, typically at day three, and as we talked about for diagnosing this, it’s a combination of recognition of alcohol withdrawal state and the presence of delirium. When we recognize a patient in our department with alcohol withdrawal, we are often using a way of objectifying the subjectivity of the withdrawal state. This is with the CIWA score and we broke it down by 8 and 16. Patients with a score of 0 to 8 is mild and they may not need any pharmacotherapy at all, but may be benefited by small doses of a benzodiazepine taper. That patient with the CIWA score of 9 to 15 is kind of that sweet spot for ambulatory outpatient treatment. So long as all the boxes are checked that they can take oral medicines, they have reasonable self-care, they aren’t suicidal, cognitively impaired. Hopefully they have some good social support and you’re able to control their symptoms appropriately through emergency department care. Patients with the CIWA score greater than 16, some will say greater than 20 are at that high risk for severe progression or have severe symptoms and need to be treated aggressively. This often will involve IV benzodiazepines, especially if the patient is intolerant of oral and adjunctive therapies with phenobarbital and propofol are commonly used. And finally, do not forget to consider the craving mitigation agent of naltrexone. For the patients that are going to be going home, making sure that they have good psychosocial support. And a final take home to remember, as we mentioned in the beginning, we see alcohol withdraw all the time. Given the lack of strong evidence showing one agents superiority over the other, there is a great deal of practice variability in how we care for these patients. There should be a few universal truths, though. We want to approach these patients not as a jaded EM physician, but as someone who cares about their trajectory and a recognition that we have a potential to really change the course of their life. Treating them with compassion, identifying their strengths and their psychosocial supports, and leaning on them, knowing our agents well and getting the proper referral can really change the course of a life for the patient experiencing alcohol withdrawal.

With that we’ll wrap up, thank you for listening!

Alcohol Withdrawal

About half a million people in the United States get pharmacotherapy for symptoms of alcohol withdrawal every year. However, a there is a lot of variability in Emergency Department management.

What does alcohol do to the brain?

First, we’re going to do a high level pathophysiology.

- Ethanol or alcohol, it is a neuro depressant.

- It affects two major receptors in our brains: GABA and glutamate.

When the brain is exposed to very high levels of alcohol chronically, the body will upregulate glutamate, and downregulate GABA. In the withdrawal state, when alcohol is removed, we do not have enough of GABA and under or unopposed glutamate.

Symptoms of Alcohol Withdrawal

Concurrent Conditions

The withdrawing patient with alcohol use disorder has the potential for many concurrent disease processes that can confound and need treatment.

Dehydration

Alcohol has a diuretic effect and will often replace water as the oral liquid of choice. If the patient is vomiting that can increase this volume depletion.

Hypoglycemia

Poor nutrition and low glycogen stores can lead to this.

Low Thiamine

This is the classic deficiency, thought to be nutritional, that precipitates a Wernike’s encephalopathy.

Hypomagnesaemia

the etiology to this is similar to above (diuresis, nutritional deficiency), but some Canadian research has shown the most common cause behind hypomagnesemia was severe chronic alcoholism. Others, however, have questioned the validity of this.

Stages of Alcohol Withdrawal

First, we’re going to talk about the timing.

Stage 1

Takes place 6-12 hours from last ingestion: symptoms of withdrawal (autonomic excitation) occur.

Stage 2

Occurs 12-48 hours from last ingestion: movement towards hallucinations and seizures.

If left untreated, it is estimated about one in three patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures will progress to alcohol withdrawal delirium.

Stage 3

Occurs 48-72 hours from last ingestion: also known as Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium (AWD), commonly called delirium tremens or DTs.

Risks for Progressing Toward AWD

- Time since the last drink

- Quantity of alcohol consumed on average

- Length of time since their last sober period

- Prior episodes of withdrawal and their progression, also known as the kindling effect

- History of seizures and untreated withdrawal

Scoring of Alcohol Withdrawal

One of the most common ways to objectify the subjective of alcohol withdrawal is with the CIWA score, this is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment.

In this scoring system, there are 10 categories with a max score of 67. Some break it down by scoring, 0-8, 9-15, 16-20 and greater than 20. Personally, I like to just use 8 and 16 – where less than 8 is mild, 9-15 is moderate, and greater than 16 is severe.

The CIWA score can be used longitudinally in a single patient. So, recognizing their score and rescoring them often every hour or two hours to see what direction they are going is incredibly valuable.

Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal

At this point, we have recognized a patient with alcohol withdrawal and scored them using CIWA. Before treatment, we need to consider a few things: the severity and chronicity of their alcohol abuse, the time since they stopped concurrent use of other sedative hypnotics, the patient’s age, concurrent diseases, and history of prior withdrawals.

Low Risk History/Mild Symptoms (CIWA 0-8)

Many patients may not require active treatment. Patients without a heavy alcohol use history, who don’t have the red flags noted above, and have minimal symptoms (categorized quantitatively as a CIWA < 8) often require no medications.

Moderate Risk History/ Moderate Symptoms (CIWA 8-15)

This is the ambulatory treatment patient, if all the boxes are checked. Patients with moderate symptomatology and fall in the CIWA range of 8-15 can be considered for outpatient management if they:

- Can take oral medications

- Have a reasonable level of self-care

- Have good social support for the withdrawal and treatment process

Comparisons of benzodiazepines to neuroleptic agents have shown neuroleptics to be inferior. The ideal benzodiazepine to use is a topic of debate.

Two Schools of Thought Arise

- Use a long acting agent like Diazepam or Chlordiazepoxide which has a smooth, nature taper given its half life and active metabolites.

- Use a short acting but “cleaner” agent like Lorazepam or Oxazepam. These agents are also metabolized by conjugation in the liver, which is less affected in cirrhosis than the CYP system (see image below). Many options exist.

How Much to Give?

Tally the total ED dose required to cause symptomatic improvement/relief and create a taper in the following manner:

- Day 1: Total ED dose of medication divided out four times a day.

- Day 2: ¾ ED dose divided out four times a day

- Day 3: ½ ED dose divided four times a day

- Day 4: ¼ ED dose divided four times a day

- Day 5: Transition off

By this period, the patient should be in contact with an outpatient provider or detoxification center. In the right clinical scenario with the right patient, these tapers can be extended to 8 days, with two days at each of above noted doses.

Severe Risk History/ Severe Symptoms (CIWA >15)

AWD is relatively rare. It is estimated to be seen in ~5% of patients admitted for management of withdrawal. Mortality rates used to be as high as 15%, but with current treatment regimens numbers are closer to 1%.

For treatment, patients with AWD require aggressive dosing of a benzo, which leads to the recommendation of IV administration by most. The dose is unique to the individual and their tolerance, but the overall goal is the same – light sedation.

Agents with good pharmacologic profiles include: Diazepam (Valium), Lorazepam (Ativan), Midazolam (Versed), and Chlordiazepoxide (Librium, not IV!).

When do you know you’ve given enough?

The answer isn’t in milligrams but in examination. Quietly sedated but rousable is the goal. To put this in a quantitative measurement, you want a RASS, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale of -1 to 0.

Adjunctive agents may be needed to achieve this. The ones with the greatest amount of literate to support their use include phenobarb and propofol. Dosing of such agents will clearly be dependent on your amount of benzo given and patient dynamics.

Adjuncts for Alcohol Withdrawal

Phenobarbital

Dosing: 130-260 mg IV every 20 minutes or 7.5 mg/kg as a loading dose*

*For patients at risk of respiratory depression, the 7.5 mg/kg loading dose will sometimes be broken up into serial doses of 2.5 mg/kg.

Propofol

Dosing: By IV infusion. Rate depending on current CIWA, benzodiazepine administration, and degree of sedation. Often requires intubation.

Check out more on managing alcohol withdrawal from our friends at EM Cases!

Episode 87 – Alcohol Withdrawal and Delirium Tremens: Diagnosis and Management

References

- Wolf C, Curry A, Nacht J, Simpson SA. Management of Alcohol Withdrawal in the Emergency Department: Current Perspectives. Open Access Emerg Med. 2020 Mar 19;12:53-65. [pubmed]

- Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. Kosten TR, O’Connor PG Engl J Med. 2003;348(18):1786. [pubmed]

- Med Clin North Am. 1997 Jul;81(4):881-907. Pharmacotherapies for alcohol abuse. Withdrawal and treatment. Saitz R1, O’Malley SS. [pubmed]

- Etherington JM. Emergency management of acute alcohol problems. Part 1: Uncomplicated withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 1996 Nov;42:2186-90. [pubmed]

- Etherington JM Emergency management of acute alcohol problems. Part 2: Alcohol-related seizures, delirium tremens, and toxic alcohol ingestion. Can Fam Physician. 1996 Dec;42:2423-31. [pubmed]

- Victor M, Brausch C. The role of abstinence in the genesis of alcoholic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1967 Mar;8(1):1-20. [pubmed]

- Schuckit MA. Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens). N Engl J Med. 2014 Nov 27;371(22):2109-13. [pubmed]

- Mayo-Smith MF, Beecher LH, Fischer TL, Gorelick DA, Guillaume JL, Hill A, Jara G, Kasser C, Melbourne J; Working Group on the Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium, Practice Guidelines Committee, American Society of Addiction Medicine. Management of alcohol withdrawal delirium. An evidence-based practice guideline. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Jul 12;164(13):1405-12. [pubmed]

- Ferguson JA, Suelzer CJ, Eckert GJ, Zhou XH, Dittus RS. Risk factors for delirium tremens development. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(7):410. [pubmed]

- Michael F. Mayo-Smith, MD, MPH. Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal: A Meta-analysis and Evidence-Based Practice Guideline. JAMA. 1997;278(2):144-151. [pubmed]

- Holbrook, Anne M., et al. “Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 160.5 (1999): 649-655. [pubmed]

- Bird RD, Makela EH. Alcohol withdrawal: what is the benzodiazepine of choice? Ann Pharmacother. 1994 Jan;28(1):67-71. [pubmed]